There is a scene in Michael Mann’s L.A.-set cops and robbers masterpiece Heat that you have probably seen, even if, for whatever reason, you have yet to see the film itself. Al Pacino’s live-wire LAPD hotshot Vincent Hanna has spent the first two hours of the film's 170-minute runtime fruitlessly chasing Robert De Niro’s Neil McCauley. McCauley is a hard-nosed professional thief who oversees a crew that operates with ruthless efficiency. After what feels like an eternity, Hanna finally has his man cornered.

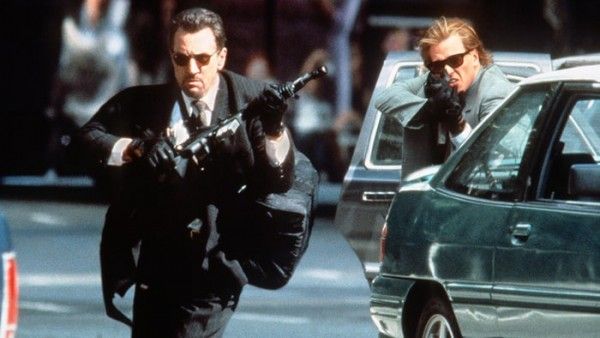

What transpires is not quite a mano-a-mano showdown, though Mann saves what is arguably his most explosive set piece for later. That would be the shatteringly brutal aftermath of a big heist that unspools into the traffic-overrun streets of downtown Los Angeles, an agonizingly protracted sequence that’s staged like a war epic in a contemporary urban setting, where machine gun rounds ring out like cannon fire. But again, that's later. First, Vincent and Neil sit down for a cup of coffee at a restaurant in Beverly Hills. The two men, we learn, have a great deal more in common than they may have initially realized.

That Diner Scene Says a Lot

Both Vincent and Neil are true, committed professionals. For better or worse, they do not place undue emphasis on the personal relationships in their respective lives. All that matters, really, is what’s right in front of them at any given moment.

There is a key, telling difference, of course. Vincent Hanna has a woman at home, even if he doesn’t seem like the most thoughtful partner. He’s irascible and frequently negligible, but he’s also doing his best. Neil comes from a more calculating and ruthless place. He, too, has a woman in his life, but she’s disposable, even if she doesn't yet know it. Neil clearly cherishes the time they spend together, but he’s also committed to walking out on this woman at a moment’s notice if he feels the “heat” coming from around the corner. That, as Neil tells Hanna, is the "discipline."

These work-obsessed loner archetypes are far from an anomaly in Mann’s filmography. If anything, they are the norm. Practically all the characters in Mann's films — the resourceful cab driver and icy hitman at the center of Collateral, the safecracker in Thief, the central subject of the biopic Ali — are myopically obsessed with what they do for a living, illegal or otherwise. What makes Heat worthy of note within the larger context of Mann’s filmography is that it’s the most honest picture he’s ever made about what a toll the work itself takes on these men. While there is an almost mythical allure to the plot events of Mann's 1995 crime mosaic — certainly, one of the great films of the 20th century — the film also offers a thoroughly de-romanticized look at the pitfalls of working overtime on either side of the law.

Pacino's Hanna Is an Obsessed Cop

In a lesser storyteller’s hands, the very character of Vincent Hanna may have come across as a risible cliché. Here is a tormented big-city cop who neglects his wife and is barely present in his personal life, all so that he may spend his sleepless evening prowling the streets of metropolitan Los Angeles, looking to apprehend small-time scum, rapists, and yes, bank robbers (or, as Hanna poetically puts it, guys who “take down scores”). It’s a testament to Pacino’s peacocking, soulful, entirely unpredictable performance — the Serpico star can take standard cop dialogue and give it an almost musical lilt — that Hanna comes across as a guy trying to do the right thing, in spite of the mounting professional obligations that are threatening to weigh him down.

De Niro's McCauley Is an Overworked Criminal

McCauley is more enigmatic, more of a cypher. He is also a character whose temperament is ingeniously suited to the actor playing him. De Niro is, for the most part, a less extravagant performer than his fellow Italian-American New York acting legend. To think that the only other time the two men appeared in the same film prior to this was The Godfather Part II, where they didn’t so much as share a single scene, simply boggles the mind. In Heat, Neil is terse, tightly wound, entirely unsentimental. He dispenses with words and actions only when he absolutely has to. He possesses an almost chilling detachment in his meticulously-laid criminal plans. Whereas other members of his crew seem to enjoy stealing for the illicit thrill it provides (who can forget the moment when Tom Sizemore’s scumbag Cherrito quips, “For me, the action IS the juice”?), McCauley’s gift for robbery seems almost involuntary. If anything, at times, it seems like an addiction.

However, there are fissures of vulnerability roiling beneath McCauley’s steely, all-business exterior. In a telling scene that occurs relatively early in the film, Neil is seen as the sole single party at a lavish group dinner where we see every member of his crew with their wives and/or children. Like Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas, Heat is a film that goes out of its way to remind us that even gangsters and cold-blooded killers have families. They're not "just like us," but they are, somehow human. Mann is also canny in his observation that Neil and Vincent’s crews are comprised of overlapping ethnic demographics: both groups are a recognizably diverse bunch, and an entirely accurate reflection of the sprawling metropolis in which their incrementally explosive conflict unfolds.

The lingering look of pain on Neil’s face when he realizes he’s the only one at the dinner table who is truly alone is almost more powerful than anything else in the film. It’s the same silent sadness that exudes from De Niro's physical frame when he finds himself unable to articulate his true feelings to Eady (Amy Brenneman), a graphic designer he ends up falling for. These are the kind of subtle, career-defining gestures that only a truly great actor can give you, and De Niro has them in spades.

In films like The King of Comedy and the under-seen Falling In Love, in which he co-starred with Meryl Streep, De Niro has expertly played men whose deep-seated emotional repression renders them unable to meaningfully communicate with women. Here, he continues the practice, but there’s something bruised and gentle beneath the surface as well. Neil absolutely understands the work he’s addicted to is slowly killing him — maybe not killing him physically, but eroding his spirit, and erasing whatever traces of empathy may have once existed in him. In the end, when the heat finally does close in on Neil, he abandons Eady. First, though, there is hesitation. Then, there is that familiar, lingering, haunted expression he gives her, right before he starts running for his life.

Mann just recently released a literary sequel to the original Heat, co-written with author Meg Gardiner. Without giving anything in the way of spoilers away, Heat 2 (which is technically both sequel and prequel) dives deeper into the rich and vivid emotional lives of Vincent Hanna and Neil McCauley. We learn that Vincent’s penchant for nihilistic hyper-fixation has always been there, that Neil has always been a slick, mechanical operator with a code. When we catch up with them in Heat, both men are fatigued, beaten down by a life that has drained them of their ability to enjoy the things that actually matter in life.

At one point in the famous restaurant scene that was cited at the top of this piece, Vincent and Hanna are describing their dreams to one another. It's an uncharacteristically sweet moment in a film otherwise filled with bullets, bloodshed, and betrayal. Neil mentions that he has a recurring dream where he feels as though he’s drowning. When Vincent inquires as to the meaning or significance of the dream, Neil’s response is curt, but also remarkably frank: “having enough time.”

Both Men Are Living on Borrowed Time

Both these men are living on borrowed time. In Neil’s case, it’s a question of logistics: no matter how cool, calm, and collected he appears on the surface, no matter how expertly thought-out his best-laid plans are, he will eventually either die in a hail of gunfire, or go back to prison. Given how the character feels about going back to prison, it would seem that he would prefer the former fate.

Vincent’s quandary is inarguably different, yet it is also inexorably tied to Neil’s. If Vincent keeps running himself ragged and exposing himself to the most wretched unpleasantness imaginable, he will eventually lose his soul. More to the point, he may lose his family, or what's left of it.

The film’s grand, tantalizing conclusion leaves the question whether or not these men will outrun their fates a mystery. Nevertheless, neither man can deviate from the path. It would go against their code. It would be unnatural. To quote Neil McCauley himself: “It’s that or we both better go do something else, pal.”