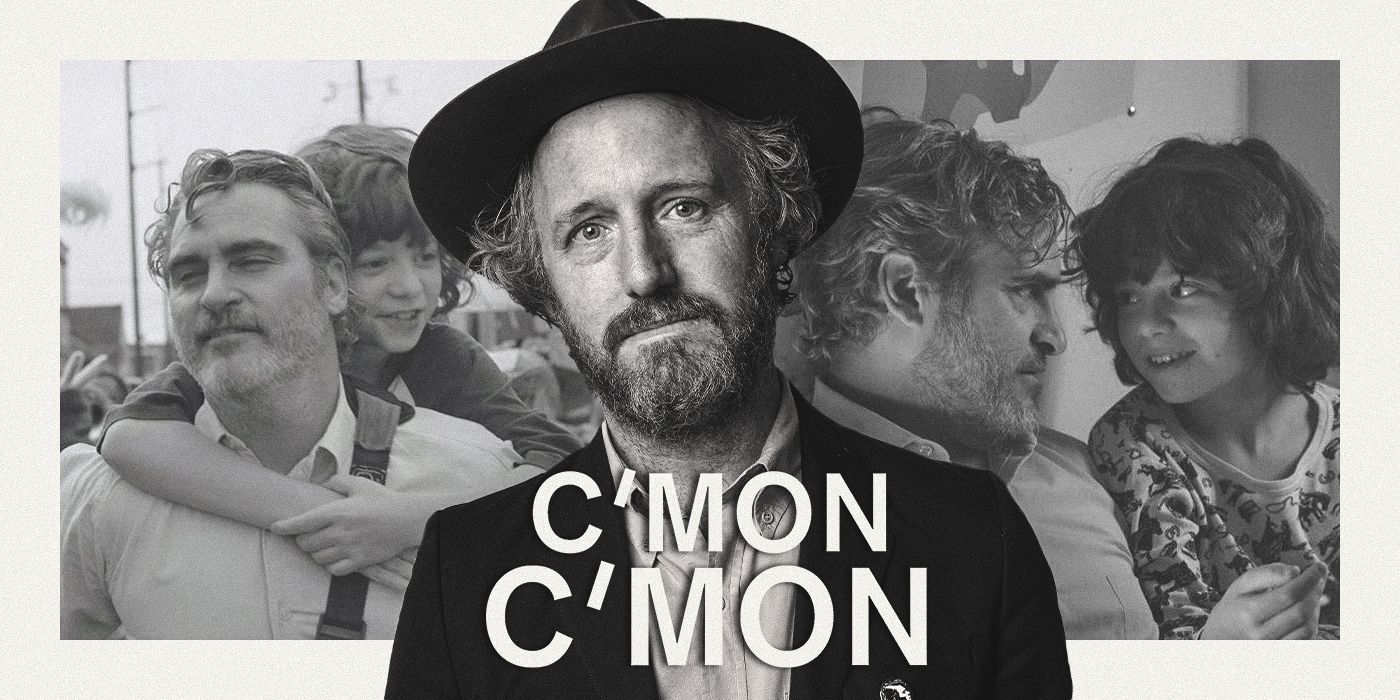

C'mon C'mon is unlike any other movie you'll see this year. Photographed in gorgeous black and white, the film stars Joaquin Phoenix as Johnny, a struggling radio producer who gets the call to take care of his young nephew Jesse (newcomer Woody Norman) when his sister (Gaby Hoffman) must attend to Jesse's mentally unwell father (Scoot McNairy). As Johnny and Jesse get to know each other through travels across the country, emotionally shifting conversations, and producing a radio show involving the real opinions of real children, their lives, brains, and hearts expand and grow in unexpected ways. I promise you, you will cry.

The film, distributed by A24, is the latest from writer/director Mike Mills, who was inspired by fathering his child, Hopper. I was lucky enough to speak with Mills in a one-on-one Zoom interview about C'mon C'mon, and we talked about the desire for spontaneity, the remarkable ability of Phoenix to blend in even as a movie star, the beyond-his-years wisdom (and love of yelling) from Norman as an actor, and the gentle coaching they would have to do if a real child recognized Phoenix as the Joker. Heck, we even discovered some new ways to describe Mills' processes that he wrote down in front of me!

But before we got into all that, we had to start with something right in front of me: A picture of revolutionary comedy filmmaker Buster Keaton, hung up behind Mills in his office...

Collider: Is that Buster Keaton behind you?

MIKE MILLS: Yeah. He's over my mantle. He's like my grandfather or something.

What do you admire about Buster Keaton? Why does he get such a prominent shrine?

MILLS: I love Buster Keaton so much. Charlie Chaplin's over there [pointing]. My office is from the '20s, and it's in Silver Lake, so this was "Silent Film World." Buster Keaton, he was an amazing writer/director, and that's my job, and I'm so proud that I have the same job. And he had his own company, he owned his production. So he found an amazing situation, and I feel like he's one of the few people that actually created the language of film. The way he worked was so independent: They have these situations, but they didn't know exactly what's happening. So in the morning they would kind of figure it out. He would just physically figure out what the scene was, and then they'd get to the end, and then the next day they'd just start where they left off, and try to figure out how to go from there to the next thing. So I love that faith and fuckin' creativity and intuition. It's like the story will come or the universe will give me something tomorrow. I find that just radical.

Is that sort of faith and that kind of creative risk-taking how you made C'mon C'mon? Is it a direct line like that?

MILLS: I don't know if it's that direct. I try to summon those things, and do in lots of little ways, for sure, all the time. Not as radically as he did, but I definitely embraced change, or I was hunting for that which I didn't plan. It's an opportunity.

Moving to that which you did plan: I find this film to be very varied in what it's exploring and touching. But when you were first writing and ideating on it, what was the initial spark? The thing that made you go, "I think there's something here"?

MILLS: Ideating is a really great word. I like that better than "writing" because I feel like that's what I do, I ideate. Writing gives me this other idea. If I say, "I got to go write," I go [mimics a robot powering down]. Because I don't feel like I'm a good writer, but I could come up with ideas, I could do that in situations.

So [C'mon C'mon] really started just [as] the very soft but powerful intimacy that you have with your kid, that I have with my real kid, and then the world of kids that my being a father introduced me to. I like stories, and I think my last three films have had this, where it's interrelational, it has things happen inside a family or primary caregivers, but it [also] has a tie to either history or just society at large. And I think when you're an adult, a parent, or a caregiver, and you take your kid's hand and you help them out in the world, you are tied to the world, all the power dynamics of the world, the future. Your life has, all of a sudden, so much more at stake, just by the help and guidance you hope to give this person. So that spectrum was the thing that made me go, "Oh, this is a film that's not just personal, but can be for strangers in a dark room."

With Beginners and 20th Century Women, which I understand to be about your parents, do you feel like making C'mon C'mon, about being a parent, has retroactively changed how you view the work you did in these previous films?

MILLS: Well, being a parent retroactively changes, cellularly reorganizes the world and the past and the future. It's that deep to me. So everything has changed. All my perspectives are changed about myself, my partner, everything. But the interesting thing that happened on 20th Century Women is, I wrote about half of it before Hopper was born, and then I finished it once Hopper was born. And it took a long time; that one took, like, two or three years. And so one of the lines in it that everyone likes is, "You get to see him out in the world as a person. I never will." So I had that feeling dropping off my kid at preschool and watching them walk off, and having this conversation with a teacher who was like, "That's a different person than the one I hang out with." And I went home and wrote it as my mother talking about me...ish. So that project had a radical shift in the middle of it, and the lines get used in all different kinds of people.

My kid came up with a line [for C'mon C'mon], "Be funny, when you can." It was advice that they were giving me. I was like, "I don't know how to finish my script. Should it be funny or not? I don't know." And then Hopper said, "Well be funny comma when you can period." Such a weird thing to say, as a seven-year-old at the time. And I loved it so much. So then in my film, it's actually what Jesse's dad says to him, so there are all these beautiful transferences that can go on with very personal material.

You touched a little bit on the idea of how being a parent becomes exploring history and the future. And I really found it captivating when the film talked to real children from across the country about what they thought of the future and history. In what way did what you learned talking to these kids or getting this footage change the trajectory of the film or how you're viewing the future?

MILLS: It's kind of how I imagined it. I've done this project before: The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art asked a bunch of people to go to Silicon Valley and make a piece, and mine was, I found all kids whose parents worked in tech companies, Apple, Google, Microsoft, Facebook, things like that, and then interviewed them about the future, because the tech world is so fascinated with the future. I thought it was changing the power tables by having their children talk about it. And I love that project so much. So I kind of knew these kinds of answers and kind of knew what was coming, a little bit. That it's more intelligent than us adults wrongly grant to young people, and darker, very knowledgeable about the limitations of our future or the threats of our future or the ecological collapse that we're facing. And that's just so heavy, but they also simultaneously always have a buoyancy, I think, just because of their energy and their developmental place.

I never wanted it to explain my characters, I never wanted to use these real kids' lives to help my plot between my two fictional characters progress. I wanted it to be setting. "Psychic child setting" or "kid perspective on the world" as a landscape that my two characters walk through. And I wanted them to be separate because I felt it would be exploitive of these kids to draft them to tell my story. But it had to relate a little bit. So that was the trickiest part, how to make sure the answers have some echo, share the same room, but are also independent and not just in use.

Touching on the idea of worrying about exploiting, I always wonder when I see a remarkable performance from a child in a film, like the one Woody Norman gives, how do you as a director take this young, forming actor to these intense places without exploiting them?

MILLS: So you pick the right person first, right? Because Woody's a very mature, very deep person, and a very "old soul," whatever you want to call it, very smart, knowledgeable, and complex, and dark, and deep, and funny, a full-on entity. So that's the first part of it. I had so much help by having Joaquin and Gabby, who are child actors. And then all my sets for everyone, I try to make them as kind and human and understanding [to] what actors are doing and making themselves vulnerable all day long and make safe space for that, make that as palatable as possible for the actor. The actors are the guests in my house and they're the guests that are putting themselves at risk, I find, and I really need them. So there's a lot of energy on my sets about how to make everyone feel comfortable. There's a lot of child labor laws that are really intense for kids working on sets. Like Woody, it's a bummer, he can only work so much — I think you work six hours a day — but then he has to go to school all the time in between. Which is good, but also, it's a lot of work. It's either acting or schooling. And we [the adults on set] all goof around. We do three scenes and then we goof around, and we do more scenes and Woody has to just go at it.

I think the trickier thing [for Woody] is doing press, to be honest. Because Woody's an actor, through and through. Loves a heavy scene, loves to cry. He learned that he loved to yell on our set. His first time he ever yelled at someone was on our [film], and you just watch this blossom happen. So acting is labor, it's work. It's Woody's talent and passion. So it's like something is happening, you're making something, you're interacting with people, it's really real. Going out and talking about yourself, or hearing your talents described back to you, [or] being praised, being put down — but praise is as potentially toxic as insults — I worry about that more than I do about making the film. And that part's just beginning. And Woody has the most amazing mom, so it's a very strong situation. But we just try to be there and we do some press together, and I'm always trying to tell Woody how great he is, because he really is, he's [a] remarkably centered, grounded, present person.

You touched on Joaquin Phoenix a little bit. When bringing in a bonafide movie star to a very found, or real, or tactile world, what do you think he added, changed, or shifted?

MILLS: Well, he added, changed, and shifted so much, but Joaquin is extremely good at blending in, too. All those shots in New York City, in the street? So we don't control the streets, those are mostly just people cruising around. No one knows it's Joaquin. He can just use the forest and just meld in, or not. So he is very strong in that way. And then doing the interviews of the kids, we worried about that, because there was so much Joker publicity happening right when we were shooting those. And once in a while, one of the kids will go, "Oh, you're the Joker!" And Joaquin would really nicely go, "Oh yeah, cool. If you want to talk about that, let's do that after. Right now, I'm really interested in this room. Where do you live? Where do you sleep? Just, cars, what do you think about cars?" And [then he was] just really listening, really interested in what they want to hear, and boop, it would go away pretty quick.

That's a really keen way to ground everyone in the present moment. What was it like watching him and Woody ground each other in these very present scenes? Was there a rehearsal process?

MILLS: There wasn't. So Joaquin and Gabby had this idea that they should meet at that scene where he walks through the door in LA. So that's where they met, they had never met before. So he walked through the door [laughter]. Woody and he met for Woody's audition, but it was months between that time and when we shot.

They were together last night; they just end up over there chatting with each other. And I don't know what they're talking about. They're joking. They're always laughing and I can't hear, and I'm not super invited. Nothing wrong, it's just they have their own little thing, right? And I think they know they have a good thing in their partnership. You know when you have a rad partner? You're like, "This is my homie, and they're helping me shine and I'm helping them shine, and it's just easy. It's copacetic." So I think that they surf on that a little bit, that they know they have a good thing. And I don't know what the heck it is, to be honest. Are they similar? Are they just two actors throwing down? Does Joaquin just really love kids? They're both really funny, I'm going to say that. They're both really, really sharp and funny and fast, so maybe they just riff on that, I don't know. But yeah, they have a thing that's not mine, I didn't create, and it's rad. And I understood that that exists for the good of the film. To promote it and just make sure the camera's on, that's my job. And they should just keep exploring that as much as possible.

I mean, it's rad that you cultivated the opportunity for them to discover this friendship, this homieship in the moment.

MILLS: Well, I think you just described directing for me. "Cultivating the opportunity to discover blank." I gotta write that one down [Mills grabs a pen and paper and starts writing]. "Cultivating the opportunity to..." Discover? Yeah. "Blank." Honestly, that's exactly what directing is to me.

I've got time for one more question for you. And it is the most important question.

MILLS: Cool. No pressure.

Did you name this film, C'mon C'mon, after the 2002 Sheryl Crow album of the same name?

MILLS: No, no. If anything, there's a great... You know this band Unrest? There's a song called "Isabel." And the chorus — it's just the background of the chorus — is like [singing], "C'mon, c'mon, c'mon, c'mon, c'mon, c'mon." And I originally had it as a long list, and that's partly why Woody says it that way in the end, as a stack. But I like it as a waterfall or a stack, and I don't really know exactly what it means, and I really enjoy that. I love the open-endedness of it. I pitched it to a friend with a bunch of other titles on the cover sheet of my script, and she was like, "That one." I was like, "Okay, that's it." I agreed. I was like, "Cool. I didn't think anyone was going to like that." And yeah, I think it comes from the rock and roll use of it. Like, "C'mon!" What does that mean? I don't know. [laughter]

What were some of the alternate titles?

MILLS: There's one called— it's not one that would work because it's another band, it's Magnetic Fields. I mean, that's such a great name for a band, but it really describes my movie, too. It's like these two souls, right? Magnetic fields that interpolate, overlap, and change each other structurally through magnetism, which is a lot like relation; it's invisible but powerful. This one was obvious; it was just "Johnny and Jessie." I found my first version of the script, of my very first draft, and it's called, "Oh, Nothing, Hooray" [laughter]. Because I get so psyched out, and I had to just tell myself, "It's nothing. This is not my next film. This is not important. This is not me trying. This is, 'Oh, nothing, yay.' It's just whatever."

C'mon C'mon is in theaters now.