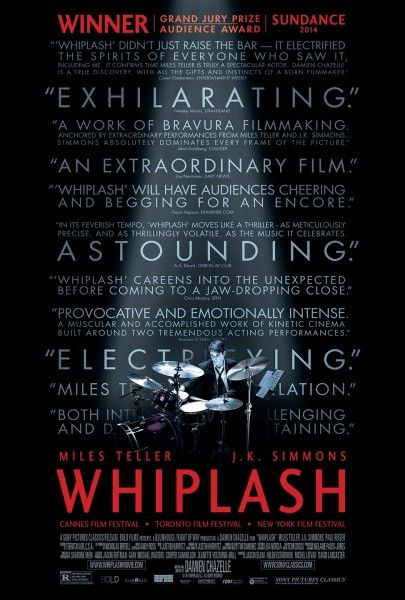

Writer/director Damien Chazelle turns the music movie genre on its head with Whiplash, an intense, exhilarating psychological drama that’s built around riveting, award-worthy performances by Miles Teller as an ambitious young drummer and J.K. Simmons as his ruthless teacher. For his impressive second feature, Chazelle pushes the boundaries in ways we’ve never seen, where precision musicianship is front and center, instruments resemble weapons, and the action unfolds on the unexpected battlefield of a school rehearsal room or on a concert stage. Opening October 10th, the kinetic, inspiring and brutally funny drama also stars Paul Reiser and Melissa Benoist.

At the film’s recent press day, Chazelle, Teller, Simmons and Benoist talked about how the movie operated differently on screen than it did on the page, bringing to life the showy roles of Andrew and Terence, how streaks of tyranny have historically led to great musicianship, how Teller’s and Chazelle’s experience as musicians channeled its way into the film, the decision to shoot L.A. for N.Y., shooting the big drum solo, the questions Chazelle hopes the cathartic finale raises, how he allowed the actors the creative freedom to explore their roles, and why this was such a cool movie to be a part of. Check out the interview after the jump:

For Miles and J.K., do you think artists want the kind of pressure that Terence Fletcher delivers?

MILES TELLER: For me, the greatest kind of success that I’ve had on a particular project or in exploring a role does come through collaboration. I wouldn’t want to do a movie where everything I do the director just says, “Good job” and I’m under directed. At the same time, I’ve done movies where I’ve felt like I was over handled and over directed, and I didn’t feel like I was able to do some stuff that I wanted to. It’s a fine line, but at the end of the day I do need somebody to see what I’m doing, because especially in film, I don’t know exactly. Even though I’m feeling it right here, maybe it’s not playing that way in the camera. I do like directors that will inspire me with ideas and give me something to chew on during the scene and to get a better performance.

SIMMONS: I hope not. I mean, masochists, I guess do. I completely agree with feeling the need for or the benefits of being pushed and of being directed on a project and collaborating. But, that kind of manipulation and abuse has no place in life.

For Miles and J.K., what was your reaction when you first read the script and what did you draw upon for inspiration to create these amazing characters?

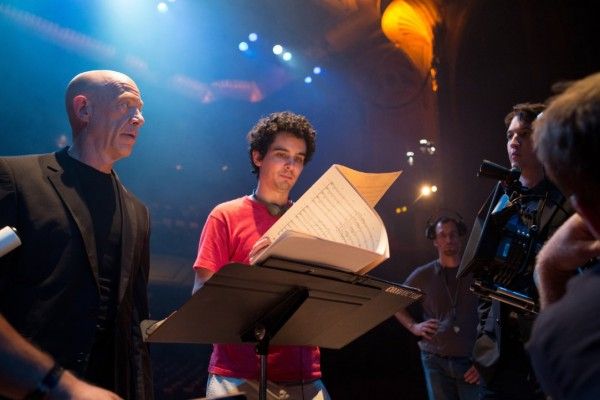

SIMMONS: Honestly, there was no conscious role model or anything that I used. I read the script and it was all there on the page. I felt like I understood it and I would be able to be the guy to help lift it off the page. Then, once we started shooting, Miles and I settled into a rhythm and had a good time, as we referred to 19 days. It was pretty much bing, bang, boom. We just went and did it and Damien turned on a camera.

TELLER: For me, it was the same thing. A lot of people have been asking me, because this movie is pretty autobiographical for Damien, “Did you ask him for advice or about the character and all this stuff?” and I said, “Not really.” I asked Damien absolutely some technical questions about drumming, because he is a better jazz drummer than I am. And so, I was using him for that as much as I could. But, for the character, it was all there on the page. It was very clear what Andrew Neyman was all about. It was probably the most clear for him as any character that I’ve ever done. With a lot of characters, there are a lot of things going on, but for Andrew, he wants to be the greatest drummer of all time and that’s his sole desire. Other than that, it was just dealing with this guy (referring to J.K.) every day on set.

Miles, I know you put your blood, sweat and tears into this film. Could you talk a little bit about that? Also, is what we hear all you or was the sound sweetened?

TELLER: I was not in the editing room for all of it. I hope it was sweetened a little bit, because at the end of the day, Andrew becomes a much better drummer than Miles was, although I have a pretty good skill set with it. It’s something that with absolutely three hours’ practice I got to a pretty good place with it, but yeah, I started getting blisters. It’s funny because when I read this script, there’s all this talk of “and the blood spatters on the cymbals.” I would come onto set sometimes and I would look at the drum kit, and there was all this blood there, and I’d literally be like, “Damien, that’s too much. No way. Get that off. It’s too much blood.” And he’d go, “No, man. When I was playing, all my drumsticks were covered in blood. This is real. This is truthful.” I started getting some bloody blisters and I was bandaging them up and stuff. It was just the nature of filming a movie like this in 19 days with very intense drumming sequences. A lot of that sweat is real and that’s great, because you don’t have to act when you’re actually playing to exhaustion. I remember J.K. told me to hold back a little bit. He was like, “Man, we’re going to have a couple takes of this. You should save some.” I was like, “Yeah, you’re right.” Then Damien would go, “What are you doing?” “I need to save some.” A lot of it was life imitating art, which was nice.

DAMIEN CHAZELLE: Miles said everything. Certainly, we did a lot of work in the editing room. A lot of it is just raw stuff from on set. A lot of it is stuff from pre-records. But everything that you see in the movie pretty much, with the exception of a few shots, is this guy (referring to Miles).

How much rehearsal and preparation was there for the acting scenes and how many takes did you actually need when you shot?

CHAZELLE: When you have this kind of schedule, we didn’t have that many takes at our disposal, but every once and a while. We didn’t have time to rehearse. The first time Miles and Melissa ever met was their first day of shooting. The first time Miles and J.K. met, we did one read through that we were able to do with the script. Everything was very kind of shortchanged. You worry about that in the moment, but when you have people like the people at this table, they brought it every day. There was a lot of stuff in the movie that we knew we had to get in one or two takes in order to allow for the things that we knew we’d have to do many takes of. For example, and Miles referred to this, the scene where J.K. is circling through the three drummers was done mainly as a single take that was done over and over and over again without cutting. We set it up so that we’d just roll the camera and the camera would roam around it. There were two cameras actually roaming around, and we did probably 12 or 15 takes of that, and it’s like a 5-minute scene. You were pretty pissed, Miles, by the end.

How about the drum solo? Did you do it more than once?

CHAZELLE: For the big drum solo, we did one master of it, and then everything else is so fragmented. I’d storyboarded everything out and done an animatic to it. So I knew, “Okay, Miles, we’re going to do measures 16 to 18 right now. Okay, cut. Now we’re going to go to the cymbal and do the coda of the song. Okay, now we’re going to do the bridge twice through from this lower angle.” We played it out that way. I remember the real trick with the solo, both for J.K. and for Miles, was continuity, because we only had extras as audience members in the theater for 6 hours, so everything pointed in that direction had to be done at once. Then, we’d flip around to these band members who wanted to let go, and then we wanted to let Miles go, and then to the band members, and then let J.K. go. So, I wanted to schedule in everything. You’d have to figure out the sweat levels. You’d be on Miles and then it’s like, “Okay, now we’ve got to do the end of the solo right now.” So Miles has to be dripping with sweat. “Okay, now we’ve got to go back to the very beginning of this song.” So Miles doesn’t have sweat yet. I just have these wonderful images of an entire posse of make-up people descending on Miles every time we’d reset up and then running away and then we’d reset up.

Miles, can you talk a little bit about your own background and musical education? Also, did you ever have somebody in your life that really drove you?

TELLER: I started with piano when I was 6 and my two older sisters both played instruments. My sister Dana is 18 months older than me and anything I would do, she would do, and vice versa. She was the only girl playing in Boys Little League Baseball, and she played on my team and she was really good. She was better at piano than I was. She played the clarinet. I played the saxophone. She was a better woodwind player than I was. Then I started moving away from that stuff into guitar and drumming and playing in some bands. Everywhere I went, my drums went with me. I went to NYU. I had a very small dorm. I lived three miles from there and I had my drum kit out in my house. I never really had a music teacher like that. There was a piano teacher that tried to push me, but I was 11 and I said, “It’s not worth it.” I quit taking lessons and just started listening to music. Then, with sports, I had a baseball coach that used to yell just for the sake of yelling it seemed like. That did nothing because we didn’t respect him. We just didn’t know where he was coming from. With J.K., you can understand where he’s coming from. He’s not just a guy yelling very funny, vulgar statements at people all day. Nobody cares about that guy.

How eager or maybe reluctant are you personally to romanticize the notion of being subjected to something that you not only survive, but you’re able to transcend and reach another artistic or personal level having gone through?

CHAZELLE: It’s tough because the movie operates on the screen in a way differently that it did on the page for me. That’s because the music itself is not on the page. When writing it, in my mind it was certainly a more tragic ending than a victorious ending and really an ending about someone gladly returning to an abusive relationship. It’s interesting, because on the screen you film a great drum solo to that kind of music and it does something. I hope that there’s still the question. My hope through the scene was to give you a certain amount of a kinetic rush but leave you with a question that maybe makes that rush a little more troubling. My hope is that that still lingers in there.

SIMMONS: I know Damien had it in mind from the beginning as he just said. It was one of the very first things that he and I talked about when we first met and sat down and thought we were pitching ourselves to each other for the job, because I wanted to do it and he wanted me to do it. It was that ambiguity. His point was to inspire discussion and debate and not decide are we happy for Andrew Neyman or are we lamenting his loss of humanity at the end of the film. Based on the reception and the discussions that we’ve been involved in so far, I think that’s exactly what he achieved. Plus, it’s just awesomely entertaining to end a movie with a 10-minute drum solo.

One thing about Andrew’s journey is his singular focus. In our internet age, when you’re supposed to be your own publicist, your own manager, tweeting, and all of this, can that still exist for an artist to be able to just make their art?

CHAZELLE: Certainly it was very conscious in terms of how I wrote Andrew and how Miles played him. Andrew is kind of an anachronism. He’s not even interested in contemporary drummers. At least I wasn’t when I was growing up. I was interested in Joe Jones, Chick Webb, Buddy Rich and Sid Kaplan. It was important to me that this was a kid who the pictures on his wall were black and white. The music he was listening to was mostly from the 70s or earlier. He held his sticks with traditional grip, whereas almost all the drummers today use matched grip. He angled his snare drum down like the old military style, whereas most modern drummers angle their snare drum up. All these little things were important. He’s the guy who lives in this artistic bubble that almost has nothing to do with contemporary life, which means whenever he exits his bubble and goes to the dinner table, he’s met with indifference or worse.

TELLER: What’s tough for an actor, especially a young actor, is you just want to work. I mean, very few actors I think are truly steering their career because it is tough if that’s all you want to do. Independent films, do they give you the most control over a character, and a lot of times, do they have the most integrity? Yeah, but you don’t make any kind of money from that. I remember Joe Pantoliano came to my class when I was in college, and people were asking his advice on how you do movies. He said, “My advice for you guys is: Do three movies a year. Do one for the money. Do one for the art. Do one for the location. You’ll be happy.” So it is. Hopefully, you can balance it out. You can do some things because maybe you want to be able to go on vacation. Maybe you want to live in a bigger apartment, so you can hopefully do something. You want to make yourself happy, but at the end of the day, we picked art as a job, as an income, so the line gets a little blurry there sometimes.

In the Drum Corps world, we had drum instructors like you and worse, but it made us better drummers and percussionists, so I understand the journey. Damien and J.K., can you talk about that experience and how important it was to convey that?

CHAZELLE: It is interesting, even as a script, the different reactions the script would often get. For people that hadn’t been drummers or hadn’t been to music school or hadn’t been in that kind of competitive world, the immediate question was always, “It can’t be like this?” I remember showing it to drummers, like this one guy who was the drummer for Jazz at Lincoln Center and had worked with Wynton Marsalis. He had a complaint as well, but the complaint was exactly the opposite. It was, “It doesn’t go far enough. It was worse for me.” What’s fascinating is that there’s this whole side of the world that most people don’t know about. A lot of music movies fit into a certain mold. It’s important to me that, if nothing else, this music movie was going to showcase things I hadn’t seen before in music movies, and that was the blood. That was the physicality of it. We don’t think of instruments as physical. We think of dance as physical. We think of sports as physical. But music we don’t. Trumpeters screw their lips up. Violinists screw their backs up. And drummers screw their hands up. So that was really important. And then otherwise, I had a teacher like J.K.’s Fletcher and it made me a better drummer. But also, as a humanist, I can’t condone what he does. I wanted to make the character as monstrous as possible so that it’s as hard as possible to condone what he does. But it’s undeniable that it’s a big part of jazz and music history this streak of tyranny leading to great musicianship.

SIMMONS: Damien and I have very similar philosophies there, and again, that’s the debate. I love that this movie is inspiring that debate. How far is too far? How much is too much? Is it worth it? I’ve made the comparison before. This kind of relentless abuse might be necessary and appropriate if you’re training Navy Seals. I don’t know if it’s appropriate in music school, but it’s there and it can be productive. There’s no denying that. It’s just from my own perspective I’d rather have a pretty girlfriend than go work with this guy and have my hands bleed all the time. I would have made a different choice.

Damien, at a time when every filmmaker or producer who possibly could was writing to New York to get the tax credits for shooting there, why did you shoot L.A. for N.Y. on this movie?

CHAZELLE: The weird answer is that it was actually a budgetary, practical consideration. I grew up in New Jersey. I grew up going into New York every weekend to go to clubs like Fat Cat and Smalls (Smalls Jazz Club) and watch jazz. That’s what I did every weekend. That was my rocking Saturday night. I wanted to shoot there. Even with the tax credits situation, what wound up making L.A. make more sense was that we had an infrastructure in place in L.A. in terms of the crew and cast we wanted to work with. For the limited amount of money and time we had, shooting in L.A. and then doing a day of exteriors in New York wound up making more practical sense. We shot mostly in downtown L.A. and had an amazing production designer, Melanie Paizis-Jones, who’s also a New Yorker. We were very conscious about not just making stuff seem like New York, but because you’re not shooting in New York, you actually have the opportunity to do something a little different. You have the opportunity to create a nightmare vision of New York that’s almost more 1970’s New York, that’s almost more like the New York of The Warriors than the New York of today. So, that was the trick for me, because downtown L.A. when you’re shooting there at 4:00 am can get pretty seedy.

Damien, what was your experience like growing up and being a drummer, and how did that inform who you are as a man and channel its way into this film?

CHAZELLE: The one kind of gendered idea that I had that informed some of that was that as a musician growing up, or artists of any stripe, versus the athletes around you, you’re immediately made to feel less masculine. Everything stemmed from that. It’s Andrew and a lot of jazz musicians of his ilk, people who are giving their heart and soul to an endeavor that is not really appreciated in the outside world. A lot of this self-hatred and hatred to other people and cruelty and emasculation stems from that. The only way that it applied to me as a kind of masculine thing -- and there are so many equivalences for women -- the only thing that applied in that sense was this idea of music and of jazz especially being sissy. It’s like you’re already not doing rock & roll, let alone football.

For Miles, in terms of what Caravan means to Andrew in the end, how does that compare to this role and what you hope this may do for your career as an actor?

TELLER: When I read the script, I was very thankful for this opportunity. I had not read a script like this that demanded so much of a character my age, let alone one where I’d get to play the drums. So, I was happy that Damien wrote something like this and that he did have me in mind for it. And then, for the others, we really didn’t have that much prep time at all. It was like three weeks going into it. You never have as much time to prepare for something as you want to. For me, this seems to be a movie where I got to show vulnerability, but it’s really a movie about drive and grit, and it’s almost shot like a boxing movie. There’s like two guys just going head to head with each other and I thought it was cool. It’s got everything in a movie that I’d want to be a part of. When I was in college, this would have been a movie that I’d have said I hope to do. It’s a movie with integrity. It’s a movie that’s unapologetic. It’s a movie that’s pushing the boundaries. And it’s a movie that should leave you talking about it and creating a discourse and having people excited to explore some of the themes in it. So yeah, this is everything that I could have asked for in a project at this point in my career.

How important is the precision that these guys were trying to achieve? How much do you think about that in terms of achieving your own artistic goals? Is improvisation more important than precision?

TELLER: I think that preparation obviously is an actor’s greatest tool, and then once you get there, you just have to respond. It’s not theater where you get to rehearse with these people and feel out beats for weeks and weeks and months and months. For this, I had an idea of what J.K. was going to do, but this movie only works if we’re in that same scene together. Damien has talked about this. It’s showy roles for both of us, but if we’re not responding to each other, then you lose so much of what is happening.

SIMMONS: That’s where the fun is. In order to be able to do that, you do need to prepare, but at the end of the day, we didn’t really prepare in terms of working on the scenes together at all. There just wasn’t time for that. I actually prefer to work that way, if I’m working with good actors who can listen and who come in with their… He had to prepare a lot with the drumming and this and that and whatever the role is. If you’re working on an accent or a dialect or specific skill set that your character has that you don’t necessarily, like playing a piano, then that’s the kind of preparation that I find absolutely necessary. For me, if the words are good on the page, the rest of it comes from spending some time with the script, and not like you’re learning lines but absorbing what the script has to offer. Then, especially with a young writer/director, to be allowed the freedom to occasionally depart from the page a little bit and just throw the ball back and forth and throw each other a curve ball was an added part of the fun, too. The fact that Damien is self-confident enough to not get his ego damaged by, “Oh wait a minute. You didn’t put that comma in that sentence.” Or “You said ‘perhaps’ instead of ‘maybe.’” That’s always a beautiful amount of freedom to have as an actor as well.

MELISSA BENOIST: The few days that I was on set I always loved how collaborative it was and how Damien worked. A lot of times, we would find the moments and the beats that we were looking for through the improv. We’d go from something where we’d say, “Why don’t we say this line?” It wasn’t necessarily rigid, but more prepared. Then the next day, he’d be like, “Okay. Throw it out the window and just see how it feels.” That kind of freedom is amazing.

SIMMONS: Collaborative is the key word there. That’s my favorite word in moviemaking.

I was intrigued by Andrew’s willingness to destroy someone he’s been so smitten with. Melissa, could you talk about your role and how you worked on that? And Damien, where did that come from? Was that a personal part of your experience?

CHAZELLE: I’ll go first just on the latter part. No, not specifically, but it certainly raises questions that had been in my mind about it. The one thing that I was looking for in this character and with Melissa was to see a little bit, like we talked about, of the human casualty of what this movie’s about and trying to remind people that other people are affected by this. It’s one thing to have Miles or Andrew strip things away in their life and devote themselves and everything, but at a certain moment, you have to look at the face of someone who’s affected by that, because it’s very easy the same way we blot out any kind of collateral damage as faceless, on an individual basis or on a political basis as a country, and that’s where it gets really troubling. On a very small micro level, it was important to me -- and I think I knew right away and we talked about this – that the breakup scene would live on her face and that Miles would look as though he had practiced this thing to a white wall, and in his mind he might as well be delivering it to a white wall, and there’s nothing there. We’re seeing what he can’t see, which is a good person being totally mistreated the same way that Fletcher mistreats everyone, and that we’re going to be on her face as close as we’re on the trombone player in Fletcher’s class or any other musician who gets utterly abused, and that he’s becoming a Fletcher. That’s how we talked about it.

BENOIST: For me, a lot like these guys, the second I read the script it was a no brainer that I wasn’t going to let myself not get the part because I knew how special it was. For me, Nicole is not necessarily that much of a departure from things that I had experienced when I moved to New York and didn’t know anyone and was going to school. I knew what I wanted to do, unlike her, but I understood from the get-go the longing for a real connection. She’s so attracted to the passion he feels because she’s lacking in a lot of ways. She doesn’t know where to put what she has inside of her. That’s a really tragic thing about her and what makes her casualty even more depressing.

CHAZELLE: We hoped that it would be a sad moment, but also the message of the movie seems to be that if you don’t know what you want to do in your life, screw you. It’s like Andrew going to the dinner table and those people are sort of assholes and you’re like, oh good for Andrew to stick up for himself there. To me, Nicole represents an approach to life that is just as valid as Andrew’s and perhaps even more valid. So it’s sad when those two things come to a head.

Damien, jazz has kind of an esoteric entry point where you get to a certain level and the only people who can really appreciate it are other jazz musicians. Can you talk about that a little bit?

CHAZELLE: It certainly makes it tricky to make a movie about someone where part of the point of the movie is that they become really good at something. I wanted to make sure at the end of the movie that we weren’t going to cut to the audience and see them going, “Whoa!,” the way some movies do to tell you that someone is suddenly good, or hear the single clap starting. We shot to nothing or maybe we had the one guy. (Laughter) It’s true that my dad’s a mathematician and I grew up on the same street as Andrew Wiles who solved Fermat’s Last Theorem, which is this game-changing event in math history. I remember when the headlines were about this 200-page proof coming out that literally five or six people, and I’m not even exaggerating, in the world can thoroughly understand. Those five or six people have to determine whether it’s accurate or not. And if it’s accurate, this is literally one of the greatest intellectual achievements in human history that five or six people on Earth can actually understand. That’s the extreme of it, but I think it’s fascinating. How do you judge what’s good or not based on that? So, there’s a little bit of my fascination with that when it comes to any sort of pursuit, especially artistic. But with Andrew, there are different kinds of drumming, and it was also a decision early on that Buddy Rich would be the style of drumming that he’d be playing. There are a lot of jazz drummers who are more subtle and whose greatness is a little harder to [assess]. If you listen to someone like Sid Catlett who drummed with Louis Armstrong, it sounds very simple at first. You have to listen for a while to realize what a genius he is. Buddy Rich’s genius is right there immediately. So, for the purposes of this movie, that was the kind of drumming that we had to go for. It’s no less valid. We definitely thought a lot about how to communicate that greatness, and not just through the music but through how it’s shot at the end. You should be able to watch the final drum solo style and still get that he’s an amazing drummer.