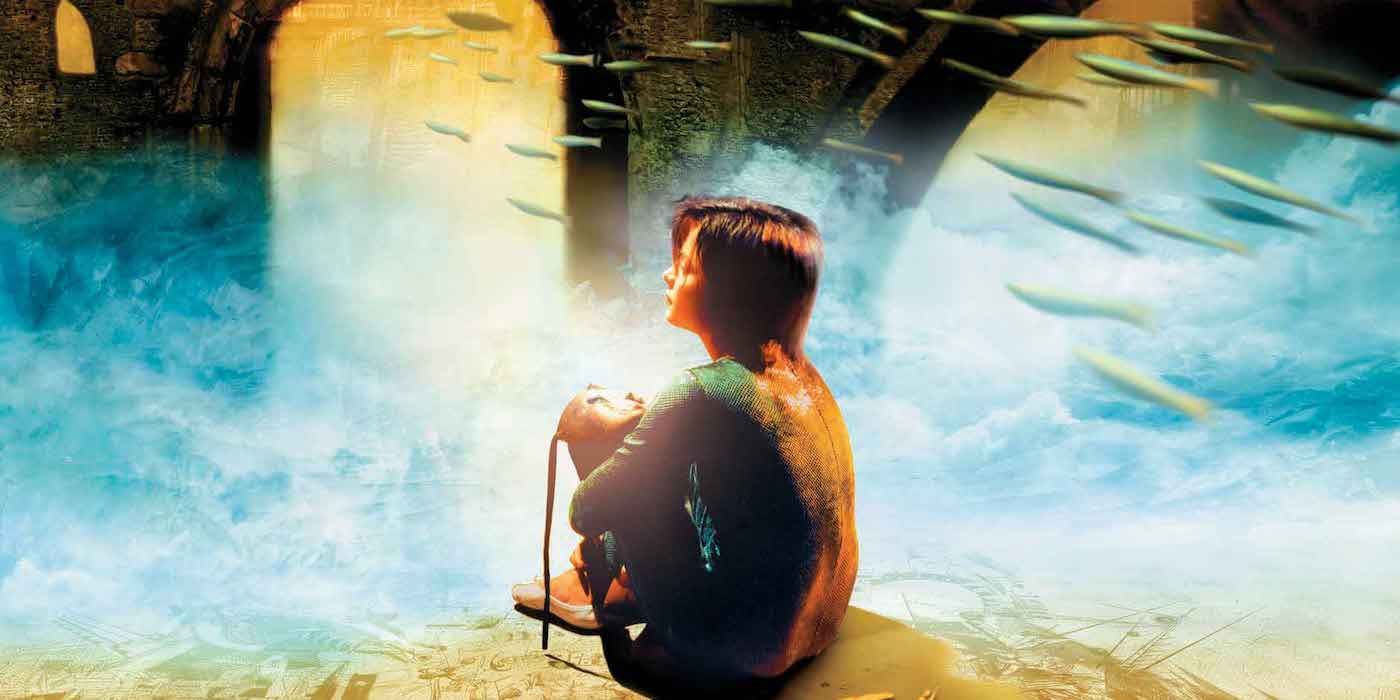

When you imagine a “coming-of-age” film, you likely think of titles such as Lady Bird or Stand By Me. You probably don’t associate them with trippy dream sequences and fantastical floating stone giants. Typically, this genre focuses on the reality and turmoil of pubescence and the protagonist(s)’ struggle to “find themselves”. Director Dave McKean, however, chooses to thrust this trope into uncultivated territory with his artistic film Mirrormask. Mirrormask is the mix of Twilight-esque quirkiness and the mesmerizing daydream-like state of Labyrinth you didn't know you needed.

Helena Campbell (Stephanie Leonidas), a troubled artist with a deep-rooted disdain for her family’s occupation as circus performers, struggles to find a place in the “real” world. Having been forced to join her parents in their traveling show for years, she grows angry and full of resentment. After an argument with her mother in which she screams, “I hope you die”, Helena is overwhelmed with remorse as her mother is unexpectedly rushed to the hospital. As the circus employees ponder what will happen to their tour without Mrs. Campbell (Gina McKee), Helena continues to lose herself within her imagination. What occurs next is a wild, trance-like excursion into a strange new world. By utilizing an alternate universe like setting — complete with Helena's evil twin — along with a devastating black sludge that, in effect, destroys everything it touches, McKean walks his audience through Helena's journey to overcome her feelings of worthlessness, repair the seemingly broken relationship with her mother, and make peace with her individuality.

At the beginning of her trip, Helena awakens suddenly in the middle of the night to the sound of violin music. She decides to investigate, thus leading her outside the apartment to a group of three performers. One rests against the cement wall playing an eerie melody, while the others juggle a few feet away. The three men are wearing masks that obstruct their faces entirely. Right off the bat, audiences are greeted with the first element of Helena’s internalized struggle with identity. The age old cliche of “wearing a mask” is given a very literal representation in the form of paper mache.

As Helena converses with the violinist, he is quickly turned to stone as a black mass overtakes his body and their surroundings –we’ll revisit this substance soon. Helena is grabbed by one of the men and pulled into a strange library as the tar envelopes the third stranger. Inside, the blackness is kept at bay while Helena and her rescuer brainstorm an escape. Eventually, they discover another exit that leads to an impressionistic city, almost resembling that of the afterlife in What Dreams May Come starring Robin Williams. There, Helena enters the dreamland in which she will ultimately discover her true self.

While lost in the alternate dimension, Helena soon realizes that she has been replaced by an evil-twin that is now jeopardizing her life back home. Every time Helena looks into a mirror or window, she catches glimpses of this villain masquerading as herself. McKean seemingly uses this element to depict Helena’s dissociation with what she sees in her reflection. Essentially, Helena feels she is constantly simulating another self in her day-to-day life; her twin is a visual representation of this. What her peers and family see on the outside is but a mask Helena wears to please them. Moreover, Helena’s twin is her selfishness and adolescent angst manifested into a tangible form, one that she must conquer and quell.

As the film progresses, viewers are met with the main conflict Helena must tackle. Within her “dream” sequence, there exists both a white and black queen (portrayed by McKee), governing two separate kingdoms. The daughter of the black queen –Helena’s twin– runs away in an attempt to escape her mother’s control, thus uprooting the entirety of her realm. Through this dissension, McKean depicts Helena’s dismay over her parents’ desire to oppress her. The black queen –representing the dominering nature of Helena’s mother — unleashes utter wrath over the kingdom to reign in her misbehaving child — Mrs.Campbell’s argumentative behavior personified. Magically, the queen produces this black substance and releases it into the world to destroy the adjacent realm of the white queen, as she believes the queen is harboring her fugitive daughter. This sludge illustrates Helena’s perception of being consumed by an identity not her own. She feels an immense sense of loss beneath the ever increasing weight to fill a certain mold; in this case, a circus performer.

As the story unravels further, Helena realizes she must retrieve a “Mirrormask” stolen by her twin to awaken the white queen –another version of her mother, but instead as Mrs. Campbell’s loving side. Essentially, Helena must find this “mirror” –her confidence in herself– before she can help save the queen –repair her relationship with her mother. As she journeys further throughout the strange kingdoms, she is greeted with a number of conflicts in which she must utilize her skills as a performer to escape or ward off villains. Through these instances, Helena finds she can thrive as her true self while embracing the talents taught to her by her parents. She understands that she can embody more than one identity at a time; she’s more than a performer, she’s whatever she chooses to be.

Finally, after discovering the key to escape — retrieved from her own reflection — Helena escapes to the real world following a final showdown with her twin. To defeat her, Helena must wear the mirrormask in order to summon the twin back into the dream realm. In this sequence of events, Helena is literally accepting her true face, thus vanquishing her internal struggle to conform. Once reinstalled as the real Helena, she quickly adjusts with a new grasp on how to begin discovering her own path.

While deviating from the standard visuals and elements of the genre, McKean’s portrayal of adolescent discovery and growth is both memorable and unique. Steering audiences away from the steortypical depiction of youth — not every teen deals with the same boy-drama as John Hughes' characters — makes for a mesmerizing and immersive viewer experience. It provides a dreamy look into a fifteen year old’s expedition through painful personal growth, familial turmoil, and her ultimate succession into self-affirmation. Helena enters her fantasy as a hurt, wounded girl, but exits an entirely fresh person, ready to be the best version of herself. Through a world of whimsical scenes and thought-provoking plot points, McKean gives audiences a story they won’t soon forget, and possibly resonate with themselves.