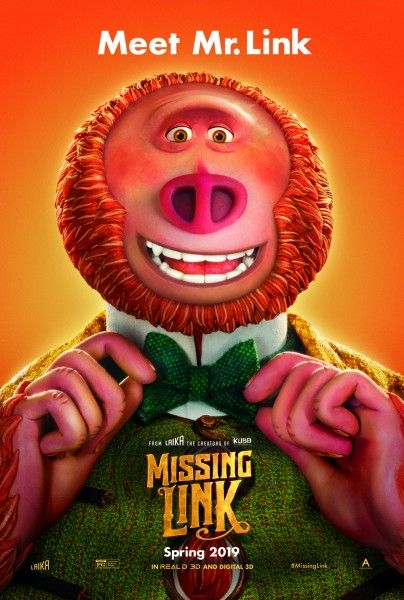

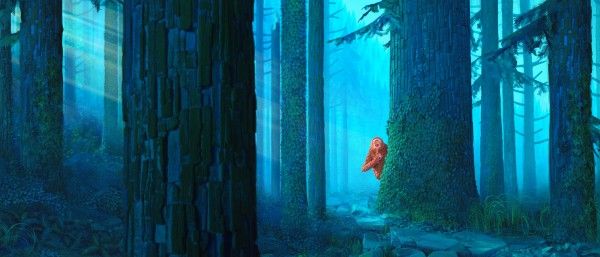

Imagine all the intricacies that go into staging an action sequence: the stunts, choreography, rehearsing, and timing. Now imagine that same process – but in stop-motion animation. A simple ten second shot of, say, Tom Cruise running down a freeway takes hours to set up and shoot traditionally, but in stop-motion: that same shot takes days, if not weeks, to film. This brings us to Missing Link, the latest stop-motion feature from Laika Studios, a globe-trotting action adventure in the vein of Indiana Jones. In the film— self-centered explorer, Lionel Frost (Hugh Jackman), journeys forth to prove the existence of the mythical Sasquatch, setting off a series of increasingly elaborate set pieces as he fends off against a rival hunter (Timothy Olyphant) and a former flame (Zoe Saldana). The action scenes – a ship-wreck, a shoot-out, a bar-room brawl, a collapsing bridge— take on an otherworldly life in stop-motion, the craftsmanship on display quite simply astonishing.

In the following interview with writer/director Chris Butler, he discusses bringing these stop motion set-pieces to life, the scene too difficult to shoot, and balancing the amount of violence in the children’s film. For the full interview, read below.

Starting at the beginning - what was the initial kernel of an idea for Missing Link?

CHRIS BUTLER: I always try to start with some kind of hook. Why make this movie? Why tell this story? For me, I'm a huge fan of Indiana Jones - Raiders of the Lost Ark is my favorite movie. I wanted to make a stop motion Raiders. So it grew out of that. Pretty much everything I loved as a kid winds up in the movies that I make. Zombies, Sherlock Holmes, Indiana Jones, Ray Harryhausen creatures. It all gets used. It's like a mixing pot of the things I loved as a kid.

What do you take away from those movies to apply here?

BUTLER: You learn a lot technically... But you know, I was working with another director on ParaNorman (Sam Fell), so that was good because I got to work with someone who had done it before. On this one, I was all on my own, so it felt like a very different experience. It's like being dropped into the deep end… The answer to your question is I learned nothing. Because what I thought was, ‘Oh yeah, I can make this movie, no problem.” And then I start -- and it's like, “This is the biggest movie that anyone's ever tried to make in stop motion. Why am I trying to do it?’

Why is it so difficult?

BUTLER: ‘Cause of the size of it. The scope and scale—it's a big adventure movie. It encompasses half the globe. I also wanted to approach it with a live-action sensibility. So there are big action set pieces with lots of quick cuts. That's how you make an action sequence in live-action. So I've got ten-frame shots, and you don't do that in stop motion because that ten-frame shot takes three days to set up. Usually, that's the first thing to go. You have to be economical. But you have to approach it that way and have the agency of something kinetic and spontaneous. That's what you're always trying to fight for in stop motion. You've got to really fake spontaneity. I'm proud of the action scenes because I think they're pretty lively.

How do you come up with these action sequences? Do you start with the location?

BUTLER: Yeah -- I knew there had to be action set pieces. So where's the most entertaining place to have a fight or a chase. A couple falls by the wayside. I had a chase sequence in the Indian jungle with an elephant being chased by men on horseback, and then they fell into a river full of crocodiles…

Why did that get cut?

BUTLER: Because that's another thirty million right there. So some things fall by the wayside. But I wanted to approach these action sequences in a ‘Spielbergian’ way. Because what I remember most from the Indiana Jones and Star Wars movies is that there's a narrative to the action sequences. There's a beginning, middle, and end. It's not just a montage of chaos. There's a shape to it - so I wanted to approach this the same way. I wanted to choreograph them. I even wrote the action sequences into the script. That's not something you're supposed to do. That's a big no-no for screenwriting. Normally people will say, "And then they fought." One line, but mine was eight-pages of dense 'Then he hits him in the side of the face, and then he falls...’ It was better written than that. They were very elaborately set up...

Did you build the script around these action sequences?

BUTLER: There's a little bit of that. I always start with the ending because I feel like it's always good when you're telling the story to know why you're telling it. It's always surprised me in animation how many times you'll work on a project where no one knows what the ending is. Then why are we telling this? So yes, on ParaNorman and this one – I started with the big climactic scene and then worked backward.

So the climactic bridge sequence – that was the first thing you came up with?

BUTLER: More or less. I knew I wanted that big sequence at the end. It was also that interaction between Piggot Dunceb and Lionel—where Lionel finally does something decent for once.

What is the balance for violence in these action sequences given it’s a children’s film?

BUTLER: You have to be very careful about that. It's certainly something we spent a lot of time on. You always have to remember who it is you're making this for. It also helps to remember yourself when you were that age and try not to get too clouded by time. Because there was a lot of stuff I enjoyed as a kid that didn't do me any harm. It's a playful tone. You can nod at something in terms of violence without it becoming grotesque. You never want it to become grotesque. You never want it to become off-putting. I think of it as a roller coaster ride. You can have tension and stakes, but you want to have a shape to it that's not just all that. It helps to lace in the comedy. If there's plenty of comedy in it than it kind of bursts that bubble and takes the edge off it. You just have to be really careful.

Was there anything that was too edgy you had to take out?

BUTLER: Probably - There's always stuff you try…

Do you test these movies with audiences?

BUTLER: We did with this one… but we probably don't do it as much as other studios. That's possibly because we're more creator-driven, more director-driven. I knew what movie I wanted to make – and it’s important to realize that and not have it become something else because of a test screening. But we did test it. Sometimes you're surprised by what people respond to.

What did people respond to?

BUTLER: The chicken.

Of course.

BUTLER: I was like, ‘really?’ The chicken's a prop. Why does everyone love the chicken so much? So I added a couple more chicken shots. I actually really like the added chicken shots. At first – I was like, ‘I'm not adding more chicken shots,’ but then I did, and I liked it.

Are there any deleted scenes?

BUTLER: It's not quite like live action in that sense because you have to be very conscious of what you're shooting. So it's more shots getting trimmed— frames here and there, rather than whole sequences of shots.

I was going to say stop motion seems so exacting – is there any room for improvisation during the production?

BUTLER: I like to say—all our improvisation is meticulously planned. I do feel for animators because that's what you want -- you want to convey a feeling of spontaneity, but it's faked. They are working on that spontaneity six weeks at a time. You have to be able to step back. It's the same for me as working on a joke. You storyboard a joke and people laugh it. And then by the eighth time that you've seen it, you're not really laughing so much. And then two years down the line - you're still working on that joke, and you're like, ‘I hate this joke.’ But you've got to be able to step back and see it for the first time. It's very difficult, but you've got to maintain that sort of distance from it.

The movie seems to be about forging your own family unit. What was it about that theme that spoke to you?

BUTLER: We've always told stories that have elements of that – finding your place. It's not uncommon for kid's movies because children don't know how they fit into the world and that's quite compelling for a kid to watch a story where someone is figuring that out, especially if it doesn't fit into the norm. That's why you often have outsiders as main characters in kid’s movies. That kind of storytelling appeals to me. What was more interesting to me in this one - was that it was from the point of view of adults, so it was more about friendships, about choosing your family. Your friends are your family. It's this collection of people who really don't know how they fit in, and maybe they don't need to. That's always been important to me as a message.

There's also some interesting gender identity politics in the film (the male sasquatch identifies with the female name Susan) -- what spurred that and how important it is to have these messages in a children's film?

BUTLER: Going back to fairy tales and the messages that are conveyed in literature in any entertainment for children, they do have something to say… I personally think it's great - giving something for kids to think about is wonderful especially if you do it in an entertaining way. It's important to me. I don't want to tell a story about nothing. I want it to have some meaning. For me, you can lose sight of why you're doing something because these things are hard and it takes so long -- and then after they're finished -- this happened on ParaNorman -- you'll get a letter from a kid who's struggling with gender identity and saying how much their movie meant to them and you're like, 'That's why we do it!'

Missing Link is now in theaters.