Gacha games have become one of the most controversial genres of gaming, but it looks like they aren’t going away anytime soon.

For the unfamiliar, Gacha comes from “gachapon,” a type of vending machine that dispenses high quality PVC collectibles with manufactured rarity ascribed to less-dispensed toys. Gacha games take that concept and apply it to popular "collect ‘em all” style games made popular by franchises like Pokémon. Most of them are free-to-play but require extensive microtransactions to reliably get rare units on a consistent basis.

As an example, I’ve been playing Fate/Grand Order for over two years. I’m a free player and have only spent around $20 on the game since getting it. I just received my first two 5-star units last week (ironically on the same pull!). The odds of getting one specific 5-star unit in the general summoning pool floats around .035%. As a casual Fate fan, I’ve never minded, but for more dedicated fans of series like Fate, Fire Emblem, or Nier, playing their corresponding Gacha games to acquire their favorite characters can be an agonizingly expensive experience.

Perhaps the most recognizable Gacha game is Genshin Impact, which grossed its first billion dollars in March 2021. Players are on record having spent upwards of $5,000 on the game and notable YouTubers have effectively boycotted it because of its “predatory” Gacha mechanics. But despite the manner in which these games prey on gamers sensitive to gambling addictions, they're not going away. Merely telling players with addictive habits not to play them does little material good in the long run, and attempting to reframe the phenomenon into healthier modes or strategies have minimal impact.

In a study published by the International Communication Association on the long-term social and mental effects on young Gacha players, it was found that teen players tend to be more susceptible to gambling addictions in gaming than older adults. There’s a number of reasons for this, including popularity among peers, competitive and cooperative aspects, and (what is potentially the strongest factor) the opportunity for “smaller” bets for “small” rewards. Teens and young adults are potentially hooked by the free-to-play model of most Gacha games, which is an effective way to retain a hefty pool of potential players. Once those players see how much more rewarding it can be to spend even a small amount of money, their monthly expenditure on the game rises.

This is all to say that Monster Hunter Stories 2: Wings of Ruin released into an odd climate for games based on collection. Pokémon Sword and Shield received a lukewarm-to-hostile reception, effectively splintering longtime fans. Pokémon’s dominance of the genre has left few true successors in its wake—Digimon continues to pump out games that sell pretty well, but they remain niche and less marketable than Pokémon with inconsistent styles and design. You could argue Shin Megami Tensei resembles the appeal Pokémon possesses, but the player’s emotional connection to their demons is deemphasized and every SMT game to date has been rated M, limiting widespread appeal.

MHS2 is the sequel to MHS, which was a well-received 3DS game late in the handheld’s life cycle. The game adds a lot of complexity to what was a relatively simple monster-collector title. In the game, you play a monster “rider” instead of a hunter as in the mainline Monster Hunter games, meaning you raise monsters instead of kill them. But make no mistake—there’s plenty of killing happening in MHS2 as well. To obtain new "monsties" (what the game calls a domesticated monster), you invade monster dens and poach eggs for hatching. If hatched in front of a rider, the newborn monstie will recognize them as a parental figure. Putting aside the moral oddity of this system, there’s a few elements of egghunting that mirrors free-to-play Gacha. Instead of catching wild monsties or obtaining eggs through breeding, there’s a random element to what type of egg you’ll get.

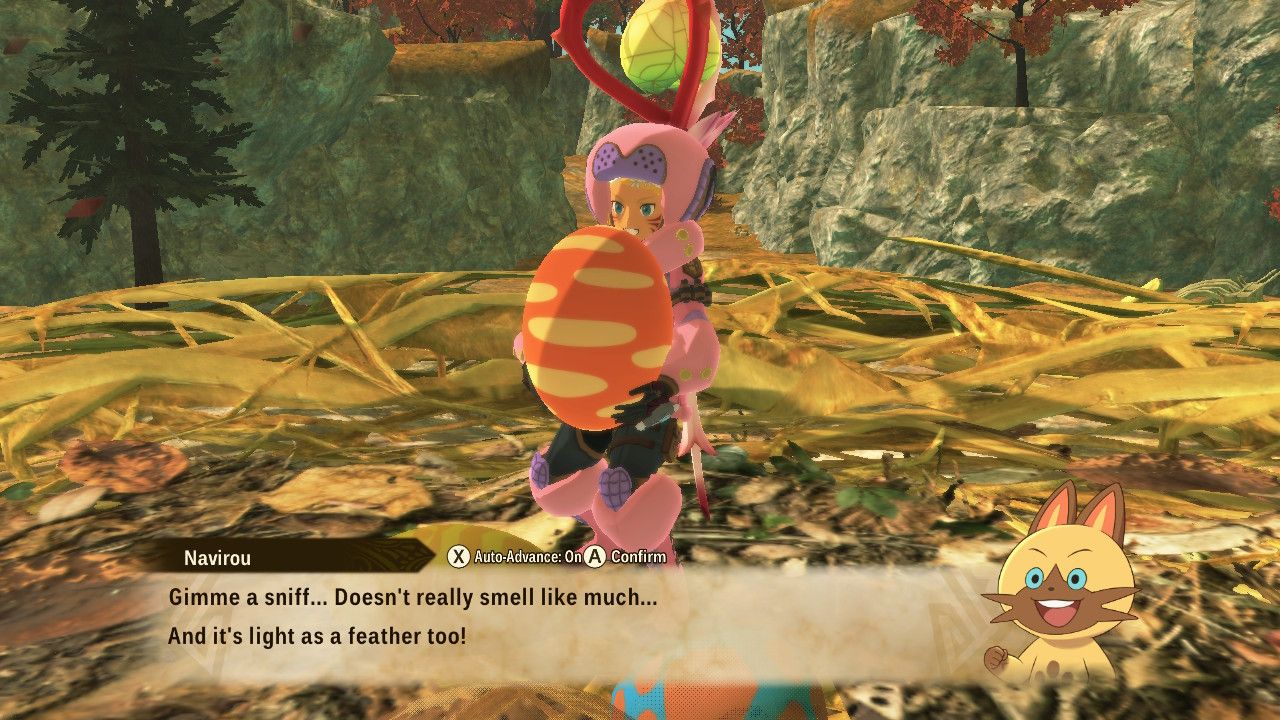

Pokémon players who obsess over the IVs and EVs of their 'mons will find a lot of enjoyment in how this works: When you reach a monster’s nest, you have the opportunity to pick up one single egg. When you do, Navirou (your buffoonish cat assistant) lets you know in vague terms how “good” of an egg it is. You can tell based on the egg’s design what monster it will be, But not what its base stats or “genes” are. Each monster can have up to nine genes that determine the moves it will learn, as well as passive abilities it may have, such as improving head-to-head victory damage or raising its kinship gauge more quickly. If you’re dissatisfied with the egg you get or want to test your luck, you can drop the egg you have and grab another until the nest is depleted.

I was initially skeptical of this because I’m the type of monster-collector who gets attached to the first Pokémon I catch. If I encounter a Oddish in the wild, name it, and travel with it long enough to have a full-grown Vileplume, I’m much more likely to keep it around even if it has a terrible Nature and poorer IVs than a new, “perfect” Vileplume I get from trading. But MHS2 has a system to account for this!

After about 10 hours in, you’ll obtain the “Rite of Channeling,” which essentially lets you expend one monstie to give one of its genes to another monstie. There’s a lot of freedom that comes with this; you can give your monstie new moves it otherwise wouldn’t learn, and also receive “bingo” bonuses that improve some of its attacks if lined up properly. This is a truly compelling system and a surefire way to carry your otherwise mediocre early monsties through til the end. It also incentivizes obtaining new monsties of species you already have in hopes of finding compatible genes for your existing monstie. The way in which you sacrifice monsties to improve existing ones greatly resembles leveling and improving your units in many Gacha games—it’s a familiar experience, and an interesting blend of these two parallel systems.

All of this, of course, applies to the single-player capability of MHS2. A Monster Hunter game wouldn’t be complete without some multiplayer functionality. Players are able to embark on co-op missions both locally and online to explore dens, slay boss encounters, or complete timed challenges. The most interesting one here is the “explore” mission type. For one, you’re able to move around the den alongside a friend and get into separate encounters against monsters (which you may or may not want to assist with). Most interestingly, though, you’re able to come away from co-op dens with multiple eggs, which can greatly expedite any grinding process you may undertake. The game goes to great lengths to make co-op battles special, too. There are a lot of ways to combine your strengths to really conquer boss battles, from flashy double attacks to increased synergy with support skills. The game allows for versus battles between teams of one or two, which can get pretty strategic and long-winded thanks to MHS2 three-life battle system.

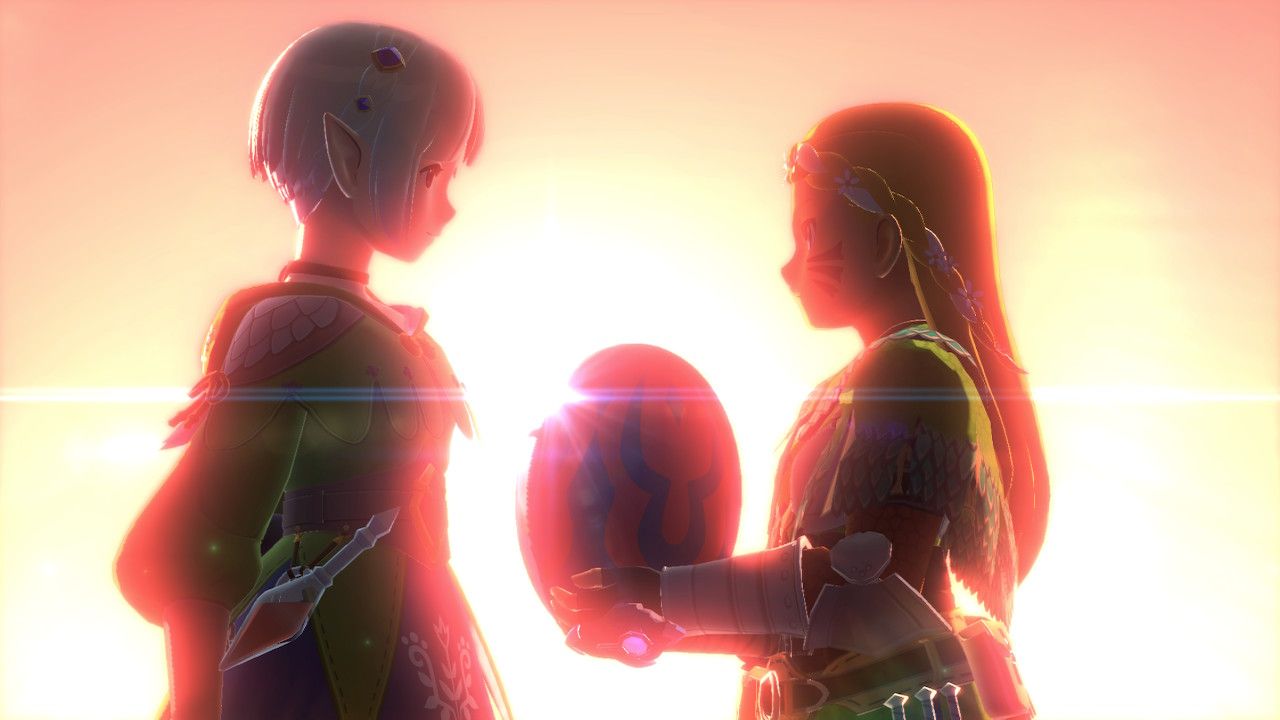

While MHS2’s plot isn’t anything revolutionary, it has enough heart and decent-enough writing to keep players invested. As a new rider, you’re sent to investigate strange occurrences making otherwise docile wild monsters go feral. Eventually you meet Ena, a Wyverian (read: elf) girl who is almost assuredly based on Zelda. She protects a Rathalos egg, which is a rare and revered type of monster that has mysteriously gone missing in recent times. The Hunter Association fears the coming of the Rathalos possessing the “Wings of Ruin,” so you wind up on the run from them as they try to capture the Rathalos. It’s all very "Saturday morning cartoon," but the gorgeous environments and lovingly rendered character models give the game a lot of heart that is often missing from games with more kid-friendly plots.

At the end of the day MHS2 is still a consumerist product, not a cure-all for any problems plaguing the gaming landscape. MHS2 includes a ton of tiny in-game purchases (most of which are outfits and hairstyles), and Capcom has announced plans to add a lot more. These kinds of minor purchases can lean toward predatory, especially for players who feel a connection to their character, Ena, or Navirou. Nevertheless, I can't help but think about how the current gaming model of continually monetizing and sustaining games well past their release date will morph in the next few years.

MHS2 seems to suggest a brighter (or at least less wholly dismal) way of doing this, and a style that I truly hope catches on. It's not the first game to include a Gacha-esque feature in a mainstream RPG—the first I can remember seeing is Xenoblade Chronicles 2, but there's surely instances before that in licensed games for Yu-Gi-Oh or the like. It is, however, probably the most mainstream and accessible example to date, and one reason I'm counting on it to instill some actual change.

While it doesn’t innovate on anything in particular, MHS2 is a game with a clear vision and an equally strong presentation. It has one of the best character creators I've encountered in a cartoon-style game, and a whole lot of heart to account for its few-but-noticeable flaws. It’s undoubtedly the best monster-collecting RPG out there right now, and I hope it attains enough popularity to stand alongside Pokémon and Genshin Impact—or, at the very least, inspire something that can compete with them.