With a never-ending supply of adaptations of spy novels, government negotiations, and undercover operations, viewers continue to be intrigued by the Cold War. The conflict's enduring appeal as a locus of moral ambiguity and psychological violence has spawned both action-packed and dramatic films addressing the secrecy, paranoia, and competitiveness of the time period. Carol Reed's The Third Man dwells on the lingering fear and ideological conflict spilling over from the Nazi years, while Martin Ritt's The Spy Who Came in From the Cold frankly addresses the results of the by then decades-old tension between West and East. With other classics starring Tom Hanks, Julie Andrews, and more, here's how these films, and others like them, have continued to fascinate viewers.

The Third Man (1949)

Director Carol Reed’s The Third Man expertly combines a noirish sensibility with an atmosphere of post-war fatigue and amorality. When American fiction writer Holly Martins (Joseph Cotten) travels to late 1940s Vienna to visit a friend, Harry Lime (Orson Welles), who’s promised him a job, he is astonished to learn that Harry is dead –– or at least, it seems that way. Holly befriends Harry’s bereaved girlfriend, a displaced young actress named Anna Schmidt (Alida Valli), who fears deportation to the Russian sector of the city. As the sinister circumstances of Harry’s mysterious death unfold, Holly, astonished by the knowledge of his friend's activities on the black market, begins to realize that nothing is what it seems.

The atmosphere of trickery pervading Vienna reflects the moral ambiguity of life in post-war Austria, and as it turns out, Holly’s American earnestness is no match for the newly de-Nazified city and its callous outlook, best exemplified by Welles's character. Unpleasant discoveries throughout the tightly paced thriller are made all the more disturbing by shadow-drenched cinematography and hair-raising zither music. The Third Man is both a genre-defining magnum opus and a brave meditation on Austria’s ability to reconcile with its dark past. It conveys an intelligent and nuanced view of post-war Europe, eschewing moralizing and instead focusing on the uncertainty and "gray areas" that many were compelled to accept following World War II.

The Spy Who Came in From the Cold (1965)

In this adaptation of the John le Carré novel of the same name, down-and-out MI6 operative Alec Leamas (Richard Burton) is sent home to London from West Berlin after the death of one of his undercover counterparts. Disillusioned by his fall from grace, he is persuaded to provide intelligence to Communist East Germany, while also befriending Nan Perry (Claire Bloom), who belongs to the British Communist Party. However, the two soon become ensnared in a larger plot orchestrated by MI6. The ensuing tragic ending offers viewers a glimpse into the ruthlessness of both British and East German intelligence operations during the Cold War.

Leamas is ultimately victimized by the amorality of his superiors, and he’s unable to accept their indifference to the consequences of their actions. It’s this sensitivity –– despite his rough exterior –– that is his downfall. He becomes yet another casualty of a conflict that's less about competing ideologies than about the distribution of global power. The Spy Who Came in From The Cold thus implicitly critiques the terms of the Cold War, in which low-level operatives function as pawns in a larger game of high-level espionage that disregards the value of human life.

Torn Curtain (1966)

Torn Curtain toys with the atmosphere of deception, anxiety, and intrigue that pervaded the Cold War years. Sarah Sherman (Julie Andrews), assistant to and fiancée of American rocket scientist Michael Armstrong (Paul Newman), becomes suspicious that her partner is planning to defect to the Soviet Union when he embarks on a secret voyage to East Germany.

Though Alfred Hitchcock’s thriller suffers from a surprising lack of chemistry between Andrews and Newman –– Andrews comes off as too prim when paired with Newman’s all-Americanness, and Hitchcock himself was unhappy with both the casting and the script –– it’s still an enjoyable Cold War romp, albeit with a slightly farcical ending. Torn Curtain expands upon Hitchcock’s creative obsession with near-misses in a world where, evidently, suspicion is the rule of the day.

The Lives of Others (2006)

Florian Henckel von Donnersmark’s devastating romantic drama delves into the lives of sophisticated playwright Georg Dreyman (Sebastian Koch), and his loving girlfriend, actress Christa-Maria Sieland (a luminous Martina Gedeck). Both have enjoyed artistic success, even under East Germany’s Communist dictatorship, but the pair are rattled by a friend’s suicide and the ongoing oppression of creative individuals by the regime. Then, Georg’s work arouses the ire of Minister of Culture Bruno Hempf (Thomas Thiene), whose predatory advances on Christa-Maria prove to be ruinous. The couple is soon unwittingly surveilled by Stasi official Gerd Wiesler (Ulrich Mühe), whose lonely personal life and apparent soullessness seem perfect for his position as an instrument of oppression. From then on, the film dwells on how the authoritarian regime co-opted friends, lovers, and neighbors through domestic surveillance, manipulation, and sexual coercion. Donnersmark's carefully paced work demonstrates the knock-on effects of these undertakings, from depression to shame. And it is frank in its portrayal of how East Germany's security apparatus affected every day life.

The ending is saved from melodrama due to its utter believability and its unflinching depiction of the cruelty of East Germany’s secret police. The Lives of Others not only reflects the impossibility of creative and emotional freedom under the Communist regime, but also reveals the significant moral damage done to the very architects of the dictatorship. Memorably, Georg’s final conversation with the ever-successful Stasi boss Bruno –– taking place after the fall of the Berlin Wall –– reveals how lightly the film’s chief villain takes his own culpability in the regime's oppression. “To think that people like you ruled the world,” Georg says.

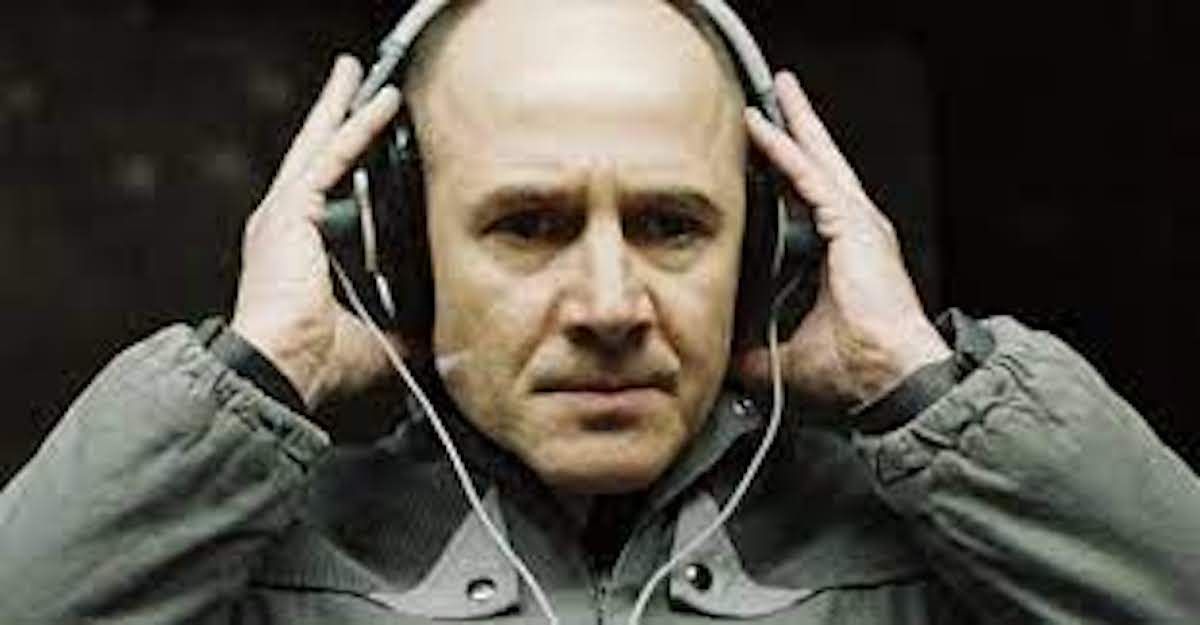

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (2011)

This second adaptation of le Carré’s novel of the same name proves to be much more intriguing than its plodding BBC predecessor, released in 1979. Picture a botched MI6 operation in 1970s Budapest, in which British agent Jim Prideaux (Mark Strong) appears to have been killed, bringing about the retirement of intelligence officials Control (John Hurt) and George Smiley (an excellent Gary Oldman). However, after learning that there’s potentially a Soviet mole in the replacement team of self-impressed MI6 operatives, Smiley takes matters into his own hands and begins interviewing fellow casualties of British intelligence maneuvers.

The fragmented nature of the narrative, and occasionally slow pacing, is offset by a brilliant ensemble cast including Benedict Cumberbatch, Colin Firth, and Tom Hardy, all of whom play individuals uniquely damaged by their roles, whether large or small, in MI6. Moreover, the film’s 1970s palette –– harvest gold, mustard yellow, and a myriad of taupes –– conveys the dreariness of post-war England and the growing sense of failure among the country’s upper-crust intelligence officials. As in le Carré's The Spy Who Came In From The Cold, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy demonstrates how bureaucracy and power games destroy trust among intelligence employees, leaving no one safe from deception or betrayal.

Barbara (2012)

Christian Petzold’s moving drama, set in the 1980s, tells the story of Barbara (Nina Hoss) an East German doctor relegated to working at a countryside clinic after she unsuccessfully makes an official request to leave her Communist homeland. Constantly monitored by the Stasi, she rebuffs the attentions of fellow doctor André Reiser (Ronald Zehrfeld), who admits that he’s required to spy on his colleagues –– including Barbara –– in exchange for the secret police leaving him alone. Barbara softens, however, when she treats Stella (Jasna Fritzi Bauer), a pregnant teenager who has recently escaped from a labor camp.

The loneliness of Petzold's characters is emphasized by their desolate surroundings. Moreover, the film's sickly color pallette and penetrating silence suggest a world stripped of beauty amid an oppressive state apparatus and long-dead dreams of utilitarianism. Petzold’s ultimate reveal –– amplified by the film’s sparse script and unvarnished look at life under the East German regime –– is part pragmatism, part sacrifice, and part romance. Barbara is the tale of one woman’s struggle to do what is right when faced with a series of devastating options. The tension between Barbara's personal desires, and the suffering she’s surrounded by, sustains the film, even when the narrative seems to move at an agonizingly slow pace.

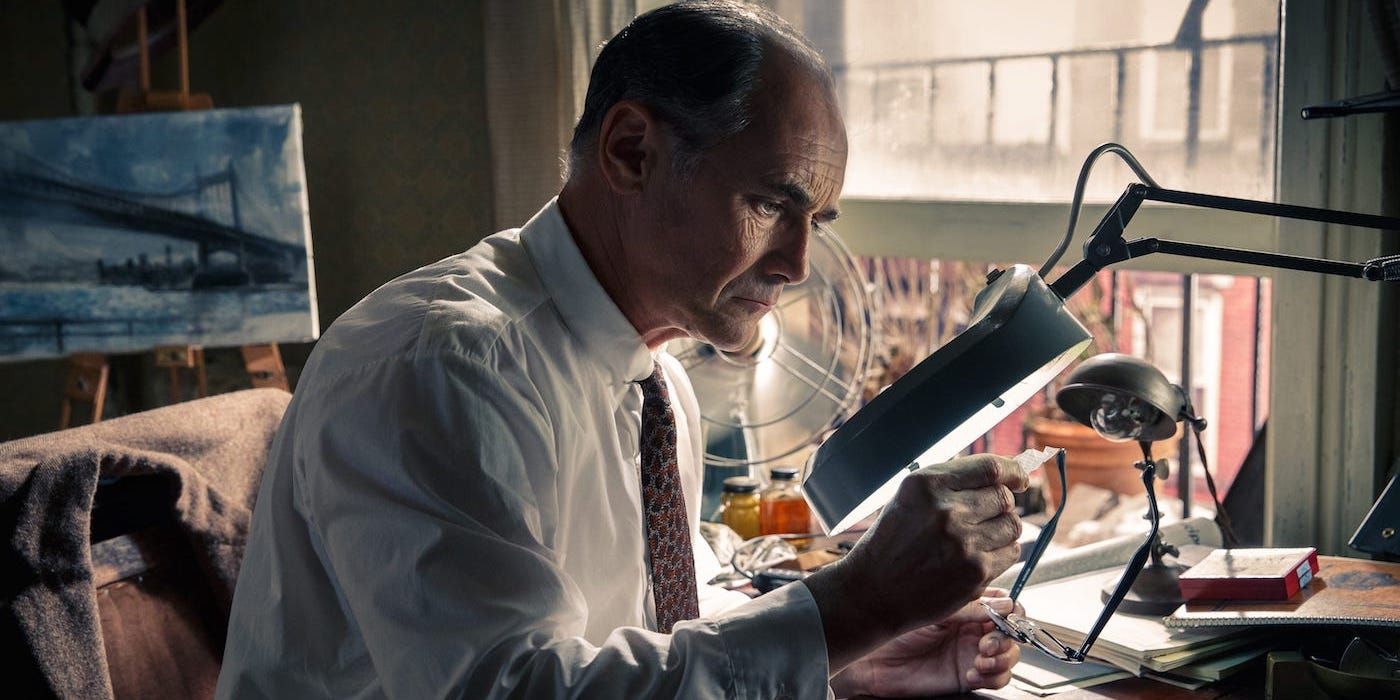

Bridge of Spies (2015)

When lawyer James Donavan (Tom Hanks) is appointed to defend Soviet spy Rudolf Abel (Mark Rylance) in 1950s America, he receives no shortage of public opprobrium –– particularly when he refuses to work with the CIA to pump Abel for information. But when American CIA pilot Gary Powers (Austin Stowell) is captured by the Russians, Donavan travels to East Berlin to negotiate for the release of both Powers and the American graduate student Frederic Pryor (Will Rogers) (imprisoned by the East Germans), in exchange for Abel’s freedom.

Hanks possesses his usual charm and charisma in the film, but the star of the show is Rylance, who won an Oscar for his role as the nearly wordless, albeit diligent, Rudolf Abel. Spielberg’s liberties with the details of the actual exchange –– famously conducted on the Glienicke Bridge between West Berlin and East Germany –– are a boon for the story’s pacing. And however harrowing the context, Bridge of Spies is ultimately a hopeful (and perhaps worryingly wholesome) tale about an agonizing prisoner exchange. Though the handoff was hardly the end to the not-so-covert hostility between the United States and the Soviet Union, the film reflects the at times arbitrary nature of the conflict, and its capacity to ruin the lives of ordinary people.