It’s hard not to be cynical about biopics. It’s true that many of them, such as Gandhi, Malcolm X, and The Social Network, are rightfully regarded as some of the greatest films of all time. But for every legacy-defining masterstroke, there are a hundred glossy pieces of hackwork that endeavor to tell the most boring possible version of their subject’s story. They’re frequently made in collaboration with the subject or their estate, which means they tend to sand down the rough edges and do away with some inconvenient truths. They stick stubbornly to the biography, containing few insights that can’t be gleaned from the subject’s Wikipedia page. The direction and craft is blandly functional in a made-for-TV kind of way. These movies exist mostly so that an actor can strap on some prosthetics, do an accent, and win an Oscar, which would be less frustrating if it didn’t work with such depressing regularity.

But let’s not talk about those kinds of biopics. Let’s not even talk about the best biopics. Let’s talk about weird biopics: the bizarre, idiosyncratic movies that reject the staid formula of traditional Oscar bait. They might forgo a prissy orchestral soundtrack in favor of anachronistic post-punk. They might ignore an infamous mob boss’ heyday and focus on his agonizing, undignified death. They might even have their subject descend from Heaven to kill Hitler. (We’ll get to that in a moment.) Most of these films are good, and some of them are truly great, but all of them are worth watching. In a media landscape that gets more predictable by the day, biopics that make bold, surprising choices should be applauded, even if they sometimes fall short of their lofty ambitions; otherwise, we’re letting Anthony McCarten win.

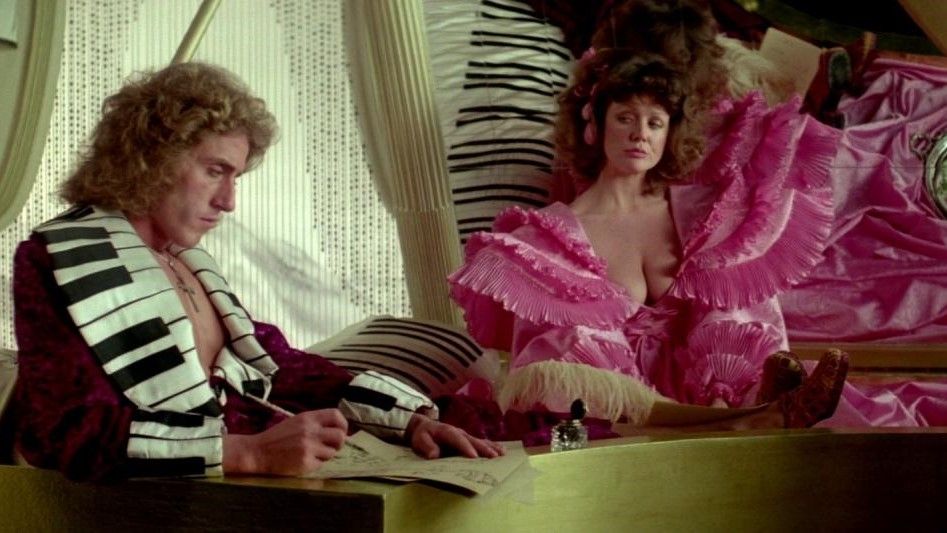

Lisztomania (1975)

Nothing can prepare you for Lisztomania. In a way, it’s unfair to the following entries on this list that this film comes first chronologically; all these movies are weird in some way, but there’s no topping Lisztomania. Directed by that beautiful maniac Ken Russell, Lisztomania takes the vague shape of Franz Liszt’s life, from the pianist’s rockstar-esque celebrity profile to his daughter’s embrace of nationalist politics. But really, the plot is just a carrying case for surreal vignettes involving exploding pianos, vampires, and delirious excess. (And penises. So, so many penises.) Russell’s gift for striking imagery, as well as some subtle commentary on the eternal nature of European chaos, makes Lisztomania more substantial than it may seem at first glance. Still, the surface pleasures are more than enough: Freudian guillotines! Pipe organ spaceships! Ringo Starr as the Pope! Are you not entertained?!

Amadeus (1984)

Is Amadeus a biopic? There are those who believe that it plays so fast and loose with the stories of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (Tom Hulce) and Antonio Salieri (F. Murray Abraham) that it can only be considered fiction. In real life, Mozart and Salieri were genuinely good friends, and there is no evidence that Salieri was filled with murderous jealousy. But while it doesn’t opt for a traditional factual account, Amadeus’ deviations from history are purposeful; in fact, it was meticulously researched. (Apparently, Mozart really did laugh like that.) By telling its own story using Mozart and Salieri as characters, Amadeus honors them both in ways a conventional biopic could never manage: they become avatars, stand-ins for divine genius and hard-working, self-defeating artistic yeomen. In a sense, they become myths; of course, Mozart didn’t need the help, which only proves the film’s point even further.

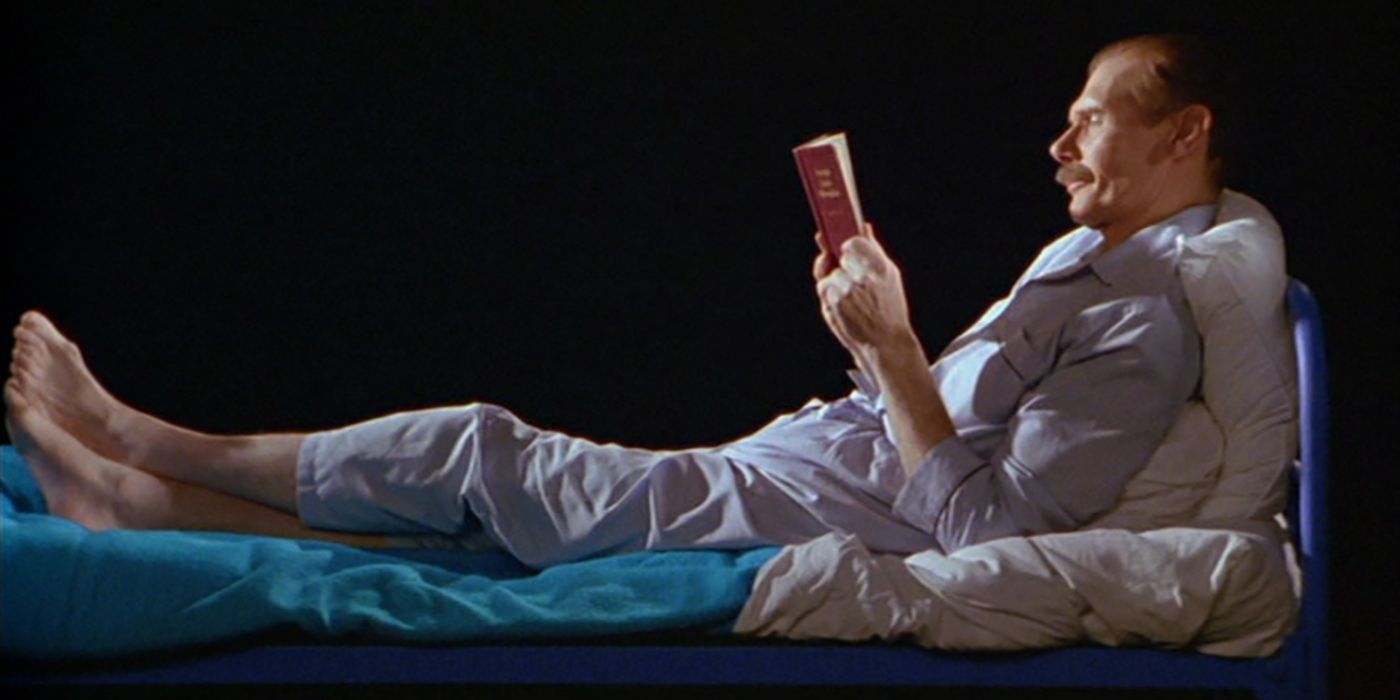

Wittgenstein (1993)

Wittgenstein, Derek Jarman’s sorta-biopic about the massively influential philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, takes place on a black soundstage, the kind where the props really look like props. It delves into the various abstract philosophical ideas Wittgenstein was known for, and while it’s often quite fun it doesn’t particularly try to make itself accessible. (A draft of the script written by literary scholar Terry Eagleton was even more dry.) Wittgenstein isn’t interested in selling modern philosophy to the hoi polloi; it’s a fiercely intellectual movie. But that doesn’t mean it’s a humorless movie, either — this is, after all, a movie where Wittgenstein repeatedly converses with an alien. Its playful use of theatrical conventions, as well as wry dialogue and a delightfully arch performance by Tilda Swinton, make it a biopic experience as singular as Wittgenstein himself.

Thirty-Two Short Films About Glenn Gould (1993)

Glenn Gould, a virtuoso classical pianist with a host of eccentricities to rival his piano repertoire, would seem like Oscar catnip to any actor and/or filmmaker who wanted to tell his story. But while Thirty-Two Short Films About Glenn Gould won its fair share of awards at the Genies (the Canadian Oscars), François Girard (who directed) and Colm Feore (who played Gould) were interested in something deeper. Thirty-Two Short Films achieves a lot over the course of its fascinating, fragmented narrative: it explores the nature of genius, it meditates on solitude, it celebrates Canada. What it doesn’t do is offer much in the way of psychological insight, which seems very much the point. Instead of taking us inside the mind of Glenn Gould, it offers viewers a window to peer through, encouraging them to draw their own conclusions about this singular man. (And yes, this is where the title of that Simpsons episode came from.)

Marie Antoinette (2006)

Words like “trifle,” “bauble,” and “confection” get thrown around a lot in reference to Marie Antoinette, Sofia Coppola’s hyper-stylized Rococo portrait of a doomed young queen. It’s true that the film is an aesthetic marvel: every frame of this movie has ended up on a Tumblr moodboard at some point, and Coppola’s flashy direction and immaculate art design often make it resemble an aristocratic music video. But beneath the pastel color scheme and post-punk soundtrack lies a thoughtful, melancholic look at a lonely teenage girl drowning in luxury. The exaggerated splendor is necessary to convey Marie’s plight: there’s a difference between not having to dress oneself and not being allowed to dress oneself. When the French Revolution shows up at her doorstep, Marie steps out onto her balcony and bows her head as though presenting it for the guillotine. After all, she had been trained her entire life to be gentle and compliant to the detriment of her own well-being. Why stop now?

I’m Not There (2007)

In I’m Not There, six different actors play Bob Dylan, including Christian Bale, Cate Blanchett, and Heath Ledger (in the final film released during his lifetime). But at the same time, none of them play Bob Dylan. They play splinters of Bob Dylan, fragments of his persona given different names and life stories. Bale plays Jack Rollins (protest Dylan) and Pastor John (born-again Dylan); Blanchett plays the dark, rebellious Jude Quinn (electric Dylan); Ledger plays actor Robbie Clark, who is playing Jack Rollins while dealing with a bad breakup, representing both heartbroken Dylan and Dylan as a performer in general. Todd Haynes understands that making a straightforward biopic about Dylan is impossible, just as it was for David Bowie in Velvet Goldmine; instead, he takes aspects of Dylan’s persona and creates new characters, who feel real and true while also reminding us that no one really knows what “real” or “true” is - maybe not even Dylan himself.

Capone (2020)

Capone is not about the rise and fall of the infamous gangster. It’s not even about the fall. It’s set long after the fall, following Al Capone’s retirement in Florida as syphilis eats him alive. Played by a magnetic, only occasionally coherent Tom Hardy, Capone isn’t just diminished — he’s downright pathetic. He lurches, shuffles, drools, and soils himself. He shouts impotent threats at alligators who steal his fishing bait. When he has a stroke and has to put away his iconic cigars, his family scoffs at the doctor’s suggestion of using a carrot as a placebo, only for Capone to happily chomp away at one without a clue (at least until he chokes on it). Capone was intended to be director Josh Trank’s comeback after his catastrophic Fantastic Four movie, but the pandemic forced an unceremonious release on VOD. It’s a real shame: in its unsparing deconstruction of gangster mythology, Capone is reminiscent of The Sopranos at its most haunting.

Spencer (2021)

Perhaps it’s not surprising that Spencer didn’t receive as warm a welcome as Jackie, Pablo Larraín’s previous biopic about a famous woman. Twenty-five years after her death, Princess Diana remains an intensely beloved public figure, and people are quite protective of her; turning her divorce into a gothic fable where she sees Anne Boleyn’s ghost and hallucinates eating her jewelry in soup struck some as tasteless. And to not only cast an American as this quintessential English rose, but Kristen Stewart? Purists, as well as those whose image of Stewart hadn’t advanced past Bella Swan, were horrified. But while its substantial festival hype only resulted in a single Oscar nomination, Spencer remains one of the best, boldest biopics in years. Boasting immaculate craft, including dreamy cinematography by Claire Mathon and an eerie Jonny Greenwood score, Spencer sets Stewart’s revelatory performance as Diana in a sprawling manor, haunted by history and the weight of expectations. Slowly cracking under the pressure, Diana is almost driven mad by what she’s expected to be - before triumphantly reclaiming her identity, at least for a little while.

Aline (2021)

There are two things that separate Aline, an otherwise quite conventional biopic about Celine Dion, from typical awards fare. For one thing, it’s an unauthorized biopic, meaning the names are changed, and the soundtrack has to weave around copyright, “Jackie Jormp-Jomp” style. Even stranger is the fact that the director and lead actress, Valérie Lemercier, chooses to play Celine (er, Aline) at every stage of her life, from 5 years old to middle age. What this means is that Lemercier, a woman in her late 50s, is digitally shrunk and FaceTuned to correspond with whatever age she’s playing. The result is a deeply uncanny mix of Baby Annette and Isabelle Fuhrman in Orphan: First Kill. It’s an incredibly disorienting choice, and the average viewer will never get used to it, but in its own weird way it’s kind of brilliant. Biopics, after all, are often an exercise in vanity, on the part of either the subject, the filmmaker, or the lead actor. Making such a bizarre creative decision pokes fun at that vanity, and serves to highlight the inherent absurdity of the whole enterprise. Aline knows you’ve seen this movie before, and endeavors to make sure you’ll never see another one without thinking of tiny, cursed Lemercier warbling “Ordinaire.”