We live in a world today where the option to watch a film is literally at our fingertips, where you can download The Super Mario Bros. Movie while waiting for Junior to wrap up soccer practice. In fact, the current generation is unlikely to remember watching films on any sort of tactile format. The generation before it knows Blu-ray and DVD. Working backwards from there, movies were available on LaserDisc, VHS, and BetaMax. Each had their pros and cons, with VHS and BetaMax memorably using those in battle to become the preferred format of the masses. Yet there is one format that predates the lot, and if you had an inkling to watch Casablanca, High Noon or The Bridge on the River Kwai circa 1972, there was one option: Cartrivision.

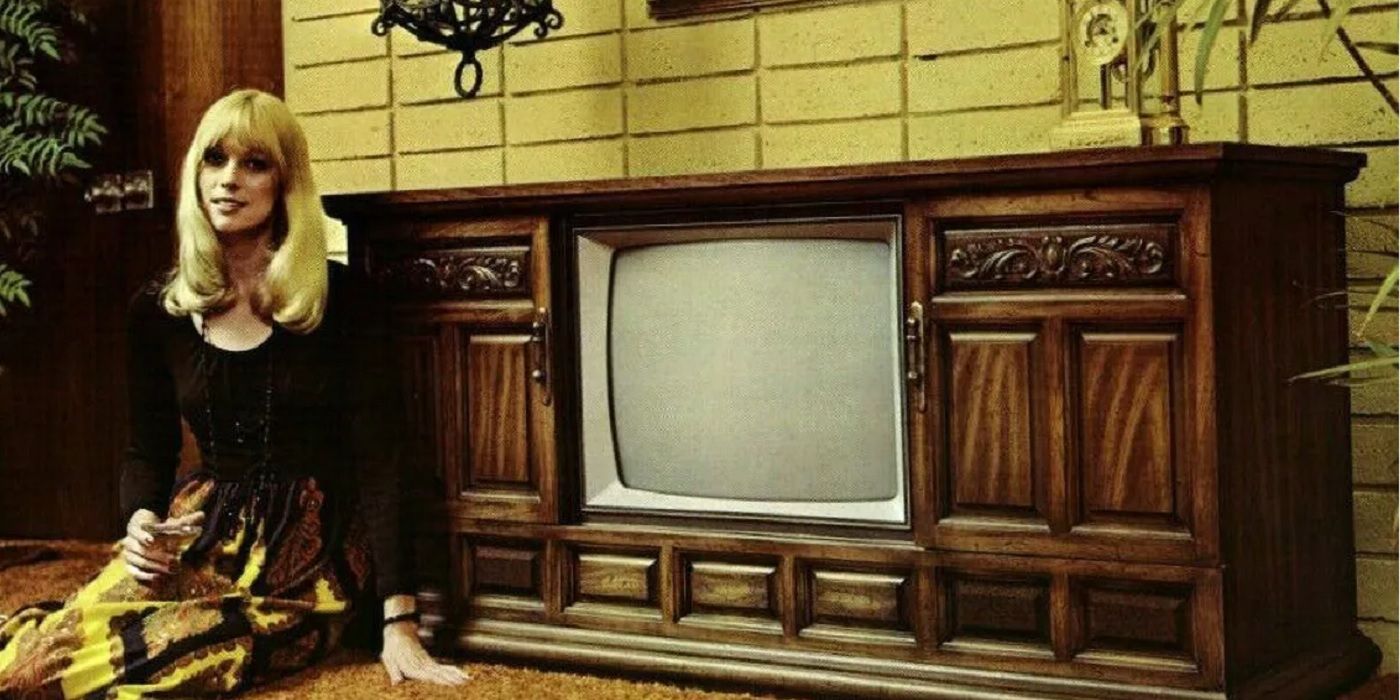

Cartrivision, developed by a subsidiary of Avco, Frank Stanton's Cartridge Television, Inc. (CTI), entered into the marketplace in 1972, a mere three years before BetaMax. Cartrivision offered many advantages that weren't readily available to the average consumer. It offered the ability to record and play back color-TV programs. It could play prerecorded videos, either purchased or rented, as well as play back home movies that were recorded on its video camera (optional). Provided you had the camera, Cartrivision also functioned as a closed-circuit security device. If you were worried that it wouldn't connect to your existing TV set, well, you didn't need to. Cartrivision was built into a 25" color television, and the whole bundle could be picked up at the low, low price of $1,350, which computes to a mere $9,797.61 today. That, by the way, was for the base model.

Cartrivision Offered Content, and Hollywood Was Okay With It

One of Cartrivision's assets was that it was easy to use. Even though one couldn't set a specific time or date to record, it did offer a count-down timer for recordings. A reusable, 8-inch square reusable cartridge, about $15 for a 15-minute tape, was available for recordings. But the true innovation was having content available for purchase or rent. Between 100 and 200 titles were available for purchase, priced between $13 and $40. Those titles, like the formats that would follow, ranged from family fare, like The Three Stooges or Roger Ramjet cartoons, up to X-rated material like the classic, Oscar-nominated Private Duty Nurses (neither classic nor Oscar-nominated, actually).

Even better, Cartrivision introduced home rental for Hollywood features, from $3 to $6. This marked the very first time movies were released to video. The available films were older classics (true classics this time) like Stagecoach, Dr. Strangelove, and Guess Who's Coming to Dinner, among others, which parent company Avco purchased the rights for (Avco also happened to own Embassy Pictures at the time, so that catalog would have been available as well). What made this development such an important moment in the history of home video is the fact that Cartrivision was able to offer Hollywood releases at all. The movie industry was deeply leery of home video at the time, fearing that it would negatively impact ticket sales. Cartrivision was able to bypass that fear by offering two different types of cartridges. Black cartridges could be recorded over, and had fast-forward and rewind availability. Red cartridges, the ones used for the Hollywood films, could only be watched once before having to be returned to the retailer for rewinding on equipment only available to them. That meant additional viewings were still being charged.

Cartrivision Never Caught On

For all that was right with the system, there were many, many problems with it as well. The video cartridges for the camera couldn't be moved from the camera to the TV console, so playback was only possible by hooking up cables to jacks. Likewise, the player itself couldn't be removed from the TV, so hooking it up to another set was impossible. The system was sold at a number of retailers — Macy's, Montgomery Ward, Sears — but salespeople didn't know much about it, selling it as a large TV set as opposed to a video player/recorder. Tapes for the machines were often not even sold on the same floor as the machines themselves. The cost of the system didn't help matters, priced well outside what the majority of consumers could afford. To add insult to injury, just before Christmas and an anticipated sales uptick, tapes that were stockpiled in warehouses were found decomposing, literally falling apart. This added to the multiple financial difficulties facing the company.

Too much? Not yet. RCA would kick Cartrivision while it was down by making press announcements heralding the arrival of the SelectaVision MagTape system, a separate component that would cost significantly less. Even more insult to more injury? RCA's SelectaVision MagTape was never actually released after all, after RCA heard rumors of Sony's BetaMax. The odds were no longer in Cartrivision's favor, if those odds even existed in the first place, and the entire endeavor fell apart once Avco discontinued production, a mere 18 months after its introduction. Avco ended up taking a $1 million write-off on the project as a whole. Consumers intrigued by the technology didn't have to wait long before the heirs to the throne arrived, with Sony's BetaMax available in 1975 and JVC's VHS format in 1977.

Cartrivision flared brightly for a time and then died quickly, but its short tenure did yield fruit. It proved that recordings of live TV could be done with ease. It taught a valuable lesson about keeping these types of machines as separate components from the TV itself, not as a single unit. Most importantly, it did open the door for Hollywood features to be viewed in the luxury of one's own home. It was still not a clear path forward, and studios fought the blossoming videocassette recorder industry tooth and nail, as evidenced in the 1984 BetaMax case that placed Sony Corp. against Universal City Studios. The first three Hollywood films available for VHS, by the way? The Sound of Music, Patton, and M*A*S*H in 1977.