Joker is a movie that loves movies. Director Todd Phillips’ expectation-busting take on the iconic supervillain, on track to become the highest-grossing R-rated movie of all time, bursts at the seams with filmmaking style. Every camera angle, piece of production design, and font choice screams at the audience, “This is a movie!” -- the perfect formal extension of Arthur Fleck’s (Joaquin Phoenix) primal need to be noticed, to be appreciated. While some MCU films feel invisibly directed, this self-contained DC title could not feel more idiosyncratic, more auteur-driven, more unique. And yet, much of the pleasures of Joker’s style comes from its borrowing of films before. Gotham City and its residents might technically exist in a fictional vacuum, but Phillips’ version is clearly in dialogue with other big-screen cities and characters. So if you’ve danced your way through a screening of Joker and want to see more stuff in that style, you’re in luck. Enjoy these 10 films that are a must-watch after seeing Joker.

Spoiler Warning: In discussing the following films, light spoilers for Joker will be revealed. Consider seeing Joker before reading. You've been warned!

Taxi Driver

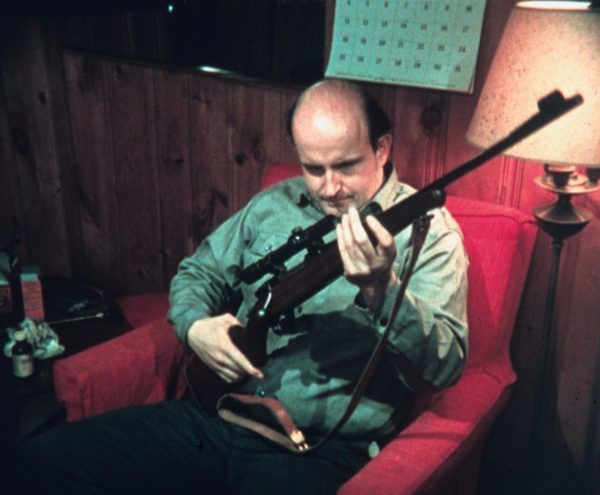

In a startling Joker moment (one of many), Arthur Fleck sits at home and watches his favorite television show, Live With Murray Franklin. He sloppily mimics the physical movements and speech patterns of his show biz hero, like the alien at the end of Annihilation watching Natalie Portman. Then, Fleck pulls out a damn gun and starts asking questions to an invisible guest, waving around his firearm haphazardly. Of course, Fleck’s gun accidentally fires into his wall, putting an end to his brief moment of imagined power. The whole sequence walks the tightrope between psychological and physical terrors, before faceplanting off the damn wire altogether. It’s also a blatant homage to Taxi Driver, Martin Scorsese and Robert De Niro’s paranoid masterpiece of antihero terror. In fact, it might even be a parody. In the iconic Taxi Driver “You talking to me?” sequence, where De Niro’s Travis Bickle points his gun at his mirror and threatens a would-be opponent, the protagonist feels in control throughout -- unlike Fleck’s clownish falling on his face. Taxi Driver is an obvious textual and formal antecedent to Joker -- Fleck is a clear update of Bickle, and Phillips’ Gotham is a clear update of Scorsese’s New York. In a grim footnote, while many in the media were quick to point out Joker as a potential inspiration for acts of mass violence, Taxi Driver did actually inspire a horrific crime -- the shooting of President Ronald Reagan by John Hinckley Jr., who became obsessed with Jodie Foster based on her performance in the film, and committed the act as a sort of tribute to her, just as Travis Bickle did.

The King of Comedy

Is it overly reductive to call Joker a “beat-for-beat remake of The King of Comedy"? Let’s look at the facts. Both involve a mentally disturbed protagonist who aspires to be a stand-up comedian. Both film’s protagonists commit vicious crimes in order to attract the attention of a late-night comedy talk show host they’re dangerously obsessed with. And both involve Robert De Niro in a key role -- the actor graduates from playing the obsessed comic in The King of Comedy to playing the talk show host target in Joker. So is Joker an unabashed bite? Well, if Scorsese is allowed to borrow from himself, making multiple movies about crime and obsession with De Niro, Phillips is allowed to borrow a little bit, too. The King of Comedy is a wild ride of a film, a work of suspense and character exploration that moves with nerve-fraying slowness until it erupts in staccato moments of intensity. De Niro’s Rupert Pupkin plays like “if Arthur Fleck had his shit together just a little more.” He wears a “normal stand-up comic suit” not with the loose, fraying edges of Phoenix, but with a starched sense of stiffness. If you thought De Niro wasn’t quite “fun” enough to play Murray Franklin successfully in Joker, that detractor might play like an asset for you in The King of Comedy. Jerry Lewis, in a startlingly self-aware performance as talk show host Jerry Langford, unfolds and unpacks the thorny relationships between a performer and his constantly needy audience. Finally, a quick “all hail Sandra Bernhard” for her fearless, raucous performance as Masha, an accomplice to Pupkin’s master plan. She steals the screen whenever she appears, and frankly, she should play the Joker in the next self-contained film adaptation.

American Psycho

How can such a nihilistic film be so friggin’ entertaining? American Psycho, the queasy 2000 horror-satire from director Mary Harron and star Christian Bale, continues to successfully punctuate its pervasive sense of pitch-black humor with shocking acts of violence upon contemporary viewing. Politically, Joker is interested in poking the hornet's nest of “1980s American class warfare and rich assholery” from the vantage point of the working class (what Phillips is saying about the working class’ point of view’s capacity for unjustified violence is worthy of a separate article). American Psycho plows through the same issue from the cynical, morally nonexistent vantage point of the wealthy class. In other words, American Psycho plays like Joker if Joker followed those Gotham finance bros on the train as its main characters. Patrick Bateman (Bale, who’d go on to play Joker’s arch-nemesis in three films) exists in a world of superficial, disposable, utterly useless masks. From his lavish skin care regimen to his robotically cheerful dissections of pop music, Bateman wears humanity like a flimsy slip tearing at the seams. To paraphrase the man himself, he simply is not there. Bateman’s only course of action in an inherently pointless world? Like the Joker, he aims to cause chaos and violence in the form of abrupt killings. Unlike the Joker, his targets move from peers (Jared Leto’s Paul Allen gets brutally axed in the film’s most iconic sequence; a foreshadowing of Phoenix brutally axing his portrayal of the Joker) to those objectively below his social status (prostitutes and homeless people), rather than the upward-facing rage inhabited by Fleck. American Psycho’s conclusions about what this all means are, by design, pointless. Somehow, this is a compliment, not a criticism, of Harron’s masterwork.

He Was a Quiet Man

If we’re gonna label “dark character studies of violent white men who are played by former teen stars” as incel propaganda, we picked the wrong one as a scapegoat. We should’ve been looking at He Was a Quiet Man, a little-seen 2007 drama starring Christian Slater. Then again, the fact that we didn’t look at He Was a Quiet Man until it was “too late” is sort of the point of the Frank Cappello-directed feature, an explicit examination of what’s going on behind the tired, polite eyes of a man with mass violence on his mind. Slater’s Bob Maconel, a pitiable white-collar office worker, fantasizes about shooting his coworkers to death (man alive, would this movie not get made today). On the one day he brings a gun to the office to go through with it, another man (David Wells) starts shooting first (He Was a Quiet Man makes a lot of upsetting ideological statements with ironically loud broadness -- one of them being that everyone is this close to snapping). Slater shoots that shooter instead, becoming an inadvertent hero and love interest to an injured Elisha Cuthbert, who had previously ignored Slater’s advances. As a whole, Joker has too much on its mind to coalesce to any kind of easy-to-pin-down thesis statement. He Was a Quiet Man, conversely, is quite blunt with its thesis. If we want to understand the psychology of the men who are prone to behaviors and thought patterns like this, this film offers more toxic insights than Joker by far. Also, if you thought Joker played its ending too fast and loose with the whole “what’s real, what’s imagined” of it all, He Was a Quiet Man’s twist ending will make your guts do a quadruple backflip. Take some dramamine before.

Entertainment

If you’re at all plugged into the Los Angeles comedy scene, you might know about Neil Hamburger, Gregg Turkington’s bizarre performance art take on the worst of stand-up comedy culture’s impulses. If you’re not -- hoo boy, strap yourself in. Hamburger has an aggressively exaggerated combover, Coke bottle glasses, and a cheesy velvet tuxedo. He holds something like five drinks at a time, spilling the liquids onto the floor as buttons to his nasally-shouted, beyond-vulgar mutations of classic joke structures. Seems like the perfect star of a feature film, right? Director Rick Alverson, who previously twisted Tim Heidecker’s persona into a nightmarish descent of detached horror in 2012’s The Comedy, hurls Hamburger into the center of 2015’s Entertainment. Co-written by both Heidecker and Turkington (whose bone-dry comedy is on full force in the multimedia On Cinema At The Cinema universe), Entertainment pits Hamburger against a litany of indifferent, sometimes hostile audiences. Hamburger responds to his uncaring public by, naturally, becoming more and more indifferent and hostile, his jokes cascading from “casual racism and homophobia” to “pretending to murder his audience by miming a mass shooting.” Famous faces like John C. Reilly, Michael Cera, and a wildly against type Tye Sheridan show up to further berate and antagonize our antihero -- in particular, Cera makes a strong case for centering his own horror movie in his disquieting sequence. Hamburger, like Fleck, gets moments of empathy with implications of a missed connection to his daughter, but his journey is mostly one of pure, unadulterated discomfort. If you were fascinated by Joker’s brief foray into the melancholy misanthropy of the stand-up comedy scene, and wanted to dive into that world headfirst, Entertainment will… well, not exactly “entertain” you, but fascinate you for sure.

Joe (1970)

Cinema of the 1970s and ‘80s, of which Phillips has cited as being a huge influence on Joker, saw a very particular subgenre explode. We’d call it something like “The Normally Normal Man Becomes a Violent Vigilante Because of the Horrible State of the Corrupt, Violent World.” Come to think of it, this is sort of Batman’s origin story, too. But we digress. Notable titles in this subgenre produced during this era include Death Wish (1974), Cruising, Hardcore, Dirty Harry, and Straw Dogs (1971). You can draw a line from any of these films, aesthetically and thematically, to Joker. But we’ll argue in favor of 1970’s Joe, starring Dennis Patrick, Peter Boyle, and Susan Sarandon, as being the most complicated and important to this subgenre. Every film mentioned (including Joker) is ideologically murky as a viewer because of its protagonist’s simplicity regarding his choices. The world is violent, so we must be violent to the world -- never mind the dubious politics behind who’s committing the “original acts” of violence versus who’s committing the “revenge acts” of violence. These films tend to show a sensitive middle-class man tapping into their dormant, “correct” modes of aggressive masculinity to lash out against a group of new-thinking folks -- often marginalized communities like poor people, people of color, hippies, or gay people. Joe, on paper, follows this mold to a T: After losing his daughter (Sarandon) to a hippie commune hellbent on pumping her with drugs and revolutionary politics, the normally buttoned-up Bill Compton (Patrick) teams up with the bluntly hateful Joe Curran (Boyle) to enact revenge. Where Joe differs from its vigilante brethren is in its attitude toward its characters and actions. From its brutal first attack, to the ugly, gut-punching twist of the climax, Joe gives you the action-packed street justice its title character would love, but complicates everything with brutal consequences. In other words, we’re definitely programmed to root for Charles Bronson and Clint Eastwood; we’re definitely programmed to find Peter Boyle vile. Joe thus makes for a curious companion piece to Joker -- does Phillips’ film like or dislike its central character’s actions?

One Hour Photo

In Joker, Arthur Fleck fantasizes about domesticity. About normal relationships. About love. These intense desires physicalize directly in confrontations with Thomas Wayne (Brett Cullen), whom Arthur believes is his father based on a narrative told by his fragile mother Penny (Frances Conroy). More elliptically, these intense desires inspire an abrupt relationship with Sophie (Zazie Beetz), Arthur’s down-the-hall neighbor. Sophie is there for Arthur as a source of comfort and release during even his lowest moments, from bombing at the comedy club to acts of murder. Until Phillips yanks the rug from under our feet, revealing that Arthur and Sophie’s “relationship” was a delusion, an empirically false manifestation of Arthur’s abject loneliness. One Hour Photo is interested in this formula of human behavior: Loneliness leading to desperate acts of fantasy leading to criminal activity. Plus, like Joker, it’s got a helluva central performance. Robin Williams commands the screen as Sy Parrish by paradoxically retreating into the screen’s negative space. You’ve never seen Williams be this quiet, this polite. And yet his work, like Phoenix’s work in Joker, functions as an extension of Williams’ more typical screen persona (which we’d loosely define as “Please like me!”). It’s just funneled into an exact opposite energy; interior instead of exterior. Sy develops photos (remember developing photos?) at a SavMart. He develops an affinity for the Yorkin family through their pervasive customership, to the point where he secretly makes copies of their photos for himself, and hangs them on the wall in his own home. We learn through brief allusions that Sy’s family situation was miserable -- through the Yorkin family, he has found a new family, no matter how one-sided. But when Sy discovers the Yorkins aren’t as perfect as their photos appear to be, he becomes a kind of “nuclear family vigilante,” making unforgivable decisions to rectify what he views as sins. From its constantly sliding scale of protagonist empathy to its exploration of "loving" obsession, One Hour Photo plays like a muted, cerebral version of Joker.

Christine (2016)

No, not the one about the evil car (although we’d love to see someone Photoshop that Joker meme into John Carpenter and Stephen King’s vehicle). Christine, an unfortunately underseen 2016 drama from director Antonio Campos (Simon Killer), dramatizes the real life tragedy of Christine Chubbuck, a depression-suffering newscaster who committed suicide on-air at the age of 29. Rebecca Hall (Iron Man 3) plays Chubbuck with nuanced brilliance. Her work is transformative, giving much-needed context to the tragedy of Chubbuck. As the Joker howls in his eventual appearance on Murray Franklin, our society has a long way to go in the fight against destigmatizing mental health struggles. Christine shows, in agonizing detail, what can truly happen to someone struggling when they’re constantly ignored, dismissed, and vilified. Particularly when they’re working in an industry powered on attention and respect; particularly when that industry is rife with broken sexism. Alongside an incredible cast (Michael C. Hall, Tracy Letts, Maria Dizzia) doing incredible work, Hall gifts us with equal parts authenticity and sensitivity. Chubbuck was a difficult person to get along with. Hall pulls no punches in portraying these difficulties. But they never cross the line into exploitation, even as Christine reaches its miserably violent conclusion. Joker may dance in and out of various lines like Arthur jumping down stairs, but Christine is always in patient control. Also, if this story fascinates you, and you want to delve even deeper into our culture’s troubling fascinations with and blurring of media representations and obsession, check out Kate Plays Christine, a mind-bending meta-documentary about an actor’s troubles playing Christine Chubbuck in a separate, unproduced biopic about Chubbuck.

Dog Day Afternoon

Todd Phillips name-checked many 1970s and ‘80s “gritty New York classics” while talking about inspiration for Joker. In discussing Dog Day Afternoon, the seminal Sidney Lumet/Al Pacino film, he said he found it helpful “because of how the anti-heroes become embraced.” Indeed, like Arthur Fleck, Dog Day Afternoon’s protagonist Sonny Wortzik walks the line between dangerous pariah and saint. In the same scene, he’s threatened with police-holstered guns on every building ledge right before getting an increasingly volatile public to scream “Attica!” with him. But there are a few key differences between Lumet and Phillips’ work, differences that make the two curious companion pieces. From a textual standpoint, Wortzik (based on a real criminal named John Wojtowicz) is inarguably more sympathetic than Fleck. While Fleck’s descent into violence is justified via a litany of potentially understandable triggers -- mental illness! Celebrity obsession! The rich get richer and society keeps society-ing! -- Wortzik’s plight can be boiled down to a pretty sympathetic motivation: Love. Well, okay, he’s choosing to express his love by cheating on his wife and committing a violent crime, but still. Relatively speaking, Wortzik > Joker. From a formal standpoint, Phillips and cinematographer Lawrence Sher are certainly interested in borrowing Lumet’s hard-boiled warts-and-all look at American cities. But they’re also interested in heightening, polishing, and even fetishizing the Lumet vibe into an aesthetic sheen. In Dog Day Afternoon, the camera simply points at NYC, with no additional flourish or gussying up. In Joker, the camera drinks in just how showily gritty Gotham feels, with Instagram-ready color correction and impeccably composed vignettes. If you dug Joker (or if you didn’t dig Joker), it’s worth watching the OG unvarnished source.

Batman: The Dark Knight Returns

Believe it or not, Joker is not the first feature film adaptation of the Batman mythos in which the Joker murders a talk show host live on the air. That dubious honor belongs to Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, a two-part animated film that adapts Frank Miller’s acclaimed and influential 1986 title. While parts of the DC Universe Animated Original Movie (y’know, DCUAOM) are somewhat sanitized, it still packs an appropriately disturbing, violent punch. Plus, when we talk about feature-length Joker performances, Michael Emerson (Lost, Saw) needs to be included in the conversation. His nervy, understated take arguably feels the closest to Phoenix’s performance. He always feels seconds away from either catatonia or psychotic explosion, and we get a lot of the latter in the aforementioned talk show sequence. Played, of course, by Conan O’Brien, the sleazy and deceiving David Endocrine (drawn as David Letterman in the comic) welcomes the Joker on-air to explain his murderous ways (much love to De Niro, but there’s a good chance O’Brien would’ve played Murray Franklin with more accuracy). Like Phillips’ version of Gotham, Miller and director Jay Oliva are particularly interested in making unsubtle comments on how 1980s consumerism, glitz, and fame distorted, amplified, and ignored our most underserved members of society in favor of cheap thrills and aesthetic violence. And what does Endocrine and his audience get for their sins? I won’t reveal exactly how they meet their demise, but the gruesome sequence plays into the iconography of both the Joker and late night talk shows. Also -- the adaptation is a nice reminder that Joker and Batman are usually in the same movie at the same time, and it’s fun to watch ‘em fight and stuff.