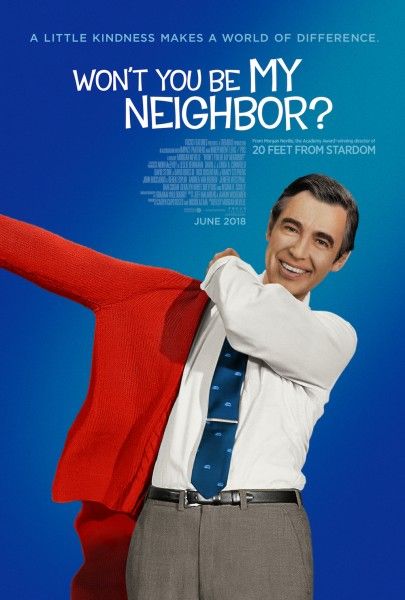

Opening this weekend in limited release is the Mister Rogers documentary Won’t You Be My Neighbor? Directed by Morgan Neville (Twenty Feet from Stardom), the documentary attempts to take a holistic look at the ideas and philosophy of Fred Rogers and why his show and life were so impactful. It will almost definitely make you cry, but in a good way. Click here to read my review from Sundance.

Last week, I got to talk on the phone with Neville and during our conversation we talked about why he wanted to make a movie about Mister Rogers, the editing process, if there was a scene that was particularly difficult to cut, if the film made him cry while making it, and more.

Check out the full interview below.

What made you want to take on Mr. Rogers as a documentary subject?

MORGAN NEVILLE: Because he's a voice I don't hear in our culture anymore. I mean, it was really as simple as that. It's me starting to go down the rabbit hole of listening to Mr. Rogers speeches and just feeling like, "This is such a profound, important message, and I'm not hearing other people speaking about these things." For years, I've been asking questions about, "Where are all the grownups in our culture? Where are the people who are looking out for our long-term best interests?" I'm not hearing anything back. So part of it was just feeling like this is ... If there's a voice out there asking people, "What kind of neighborhood do we want to have? How do we be good neighbors?" That that was something that I just wanted to spend time with and think about and put back into the culture.

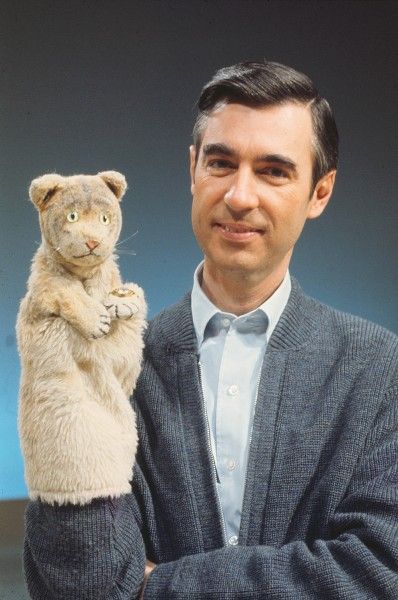

What do you think made Fred Rogers such a singular figure in our culture? What was it about him?

NEVILLE: I mean, he was both a singular person really unlike most anybody else. He also came along at such a perfect time. I think if he'd been born five years sooner or later it would have been a very different story. I mean, he happened to, just at the perfect moment in his life, see television and change his entire life's course. Instead of going into the seminary, he moved to New York, and he worked at NBC to learn the ins and outs of television and dedicated himself to television, he said, "Because he hated it so." But he saw the potential in it, and he knew that this was going to be the most powerful technology of his life and it also had the potential to do the most good. He believed television had incredible potential for goodness, but that it was likely misused. But even by the '80s, he said, "If I came on today, I wouldn't get a TV show."

I think it happened kind of organically in a way that was not only ahead of its time, but I think it's kind of out of time. In that, you know he was doing a show for essentially two to six-year-olds talking about things like death and war and divorce. And I haven't seen anybody do that ever, even before a sense.

I think what his sense of what he wanted to do was just different from everybody else's. And in fact he didn't like television, he didn't like fame. Those were just the necessary byproducts of what he did like, which was being able to communicate to children and try to help them.

Can you talk a little bit about the editing process for this film because one of the remarkable things about it is that there are subjects that feel like they could be spun out into their own feature. Like Mr. Rogers and his faith, or Mr. Rogers and his personal family, or Mr. Rogers and just the television age. This is a very holistic documentary and yet there's so much that feels like it could be it's own film.

NEVILLE: Yeah. I mean, my way of focusing the film, and this is from the very beginning. When I went down to Pittsburgh to meet with Joann Rogers, my pitch was I don't want to make film about the biography of Fred Rogers, I want to make a film about the ideas of Fred Rogers. And she said "Fred would appreciate that because he always said if anybody made a film about his life it would be the most boring film of all time." Which I thought was funny and cute.

But that ... The ideas were the things that he cared about, but also it's really where all the conflict came form. Essentially he was fighting, as he saw it, a battle to try and protect children from the, as he said "The ever ready molders of their world." If television was there to essentially sell toys and sugar to kids, he wanted to be more than that. He understood that there would be generations of kids raised by television and that they needed something more than just what everybody else was giving them. They needed an adult who could look out for them.

I know I'm drifting from your answer here, but I think it was just this idea that he was trying to understand his kind of intellectual mission and spiritual mission that became the through line for the film. And there were so many other things that we had to cut out just because there were over 900 episodes of the TV show, and there were so many other bits of video and things we had. I think I did 30 interviews and we needed up using less than 15. I think part of my process is casting a wide net and then just skinning it down to the bone at the end.

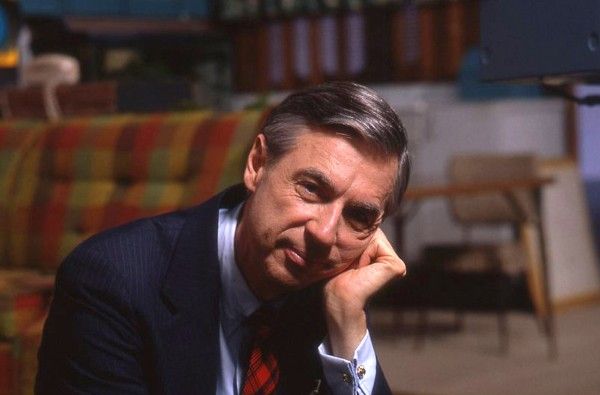

And essentially I feel like Fred's message was always simple and deep. People thought ... I think the misreading of Fred is he was simple and superficial. But he was profound in so many ways. And so really in honor to that I think we wanted the film to be simple and deep. To appear really straight forward, but to carry that profundity with it.

Was there any scene that was particularly difficult to cut?

NEVILLE: I mean there were a couple things that I liked that we cut. I mean there was a number of different things. There was a scene about how he used to go back into old episodes that he thought he hadn't aged well, because he had maybe made a comment that has presumed that a woman may be working as a secretary or that he'd used a personal pronoun of he when it should have been they. That he would go back and dress up in the same clothes and shoot inserts and fix all old episodes where he felt that he hadn't been sensitive enough. Which is kind of remarkable.

I've never heard of anybody doing that. I kind of wish that that was in there. There's a whole other great story that's not told about, you know his dad was always interested in music and also try to stay connected with his teenage boys. And he said his dad always wanted to know what was happening so he said he'd give his dad Frank Zappa and Fred would find it very interesting because Fred loved composition. But he said that the artist my dad loved the most of anything I gave him was Bob Marley. He loved Bob Marley's music.

If you think about it, the Bob Marley message is very similar to Fred's message. But he said "Of course I didn't give him the ganja song. Just the love songs."

Was this a film that make you sort of cry as you were making it?

NEVILLE: It did. I mean, even when we mixed the film we did our final mix and then we sat back to watch the final mix, and I started crying. And I'd made it! So, it was something I found personally very emotional. But I honestly had no idea how that would translate to an audience. In my experience of screening it in theaters of people, is that surrounded by people it just heightens that experience. And I thought a lot about why that is. And one answer I have is that Fred speaks like a child. And I mean that in the best way. It's just that children are very direct. They'll tell you what they think. They'll ask the questions they want to know. And as we grow up we don't ask. We mask intentions and hid emotions. But that Fred would have none of that. That he always wanted to zero in on exactly what it was that troubled you or what you wanted to know or what you felt.

And as a viewer spending that much time with him, then ultimately he's going to win. Ultimately he is going to get beyond your adult defenses and ask some question that's going to get to the core what it is you really are grappling with. For me that's, yeah it's that emotional directness ultimately will melt the most cynical of hearts. And we live in a cynical age too, it's very easy to be cynical about somebody like Fred Rogers.

But I actually feel like he is kind of a good antidote to cynicism.

I agree. I wanted to also talk to you about the animated sequences and your decision to sort of integrate those into in film, and how those came about.

NEVILLE: Yeah. I mean part of it was trying to avoid the film being a bio doc in the traditional way. And really think about Fred's childhood is the place that inspired his work. And so looking at his childhood less as the facts of his childhood and more what were the feelings of his childhood that he pulled on and used as an adult.

And as you learn in the film Daniel was the perfect avatar for seeing Fred as child. And Fred himself would say that. So Daniel kind of was the embodiment of the young Fred. And had all those insecurities. All those insecurities Daniel talked about all the time. And Daniel from it's earliest days, we talked about it some in the film, but that Daniel is a tame tiger. Which means that Daniel started with some sense of rage, that there was something to tame, and that for Fred there was something to tame too. So it just felt like, for me, that was a way for talking about his childhood but keeping it kind of in Fred's ... Keeping it with his feelings and his ideas and less kind of from the outside.

One of the things I love about the film is that it's not about what would Fred Rogers do, it's what would you do. Was that something that you came in with at the beginning or was that something that you found along the way?

NEVILLE: It's from the beginning, absolutely. Because I felt like Fred was always about asking questions. And I feel like what I do for a living is ask questions too. I feel like it's more effective politics, it's more effective ministry, it's a more effective film making if you challenge, or you could say empower, the audience to fill in their own answers. And I felt like this was a film that I really wanted to challenge the audience with and make them fill in their own feelings to answer those questions. So, yeah that was something that was there from the beginning. Before we even started making I knew that that was the note I wanted to end on.

To follow up on that: Did you know then that you would end on that question then? And I don't want to spoil it for people who haven't seen the film yet, but there's a very profound question at the end of the film. I was wondering if that was always there?

NEVILLE: I didn't know that was going to be the ending. I mean I shot every interview like that, but I didn't know even if it was going to make the film. But it actually, for me, just happened to work perfectly well. And I feel like it's keeping in line with the idea of the film transitioning from Fred to kind of transitioning into the world. And of course that was something Fred did in his own speeches. It was always trying to get people to be mindful.

I mean now in out culture there's this whole kind of ... People talk about mindfulness now. And I feel like that was what Fred was always doing. He was asking people to take the time to be mindful. Because there's so much thoughtlessness everywhere. And so in that way. Yeah I think it was ... I'm all for more mindfulness.