“Maybe my next movie will be a musical” is a phrase you’ll often hear from film directors who have conquered every other genre under the sun. The musical is no doubt an alluring genre to directors with a certain amount of hubris for the sheer amount of technical mastery involved, since it adds on singing, choreography, and agile camera movement to all the other various skills that go into making a film pop. This degree of difficulty might explain why the musical is a genre that’s often relegated to directors who have the certain skills associated with the musical, take for instance a Rob Marshall, a Jon M. Chu, and, in a different era, a Vincente Minelli.

And yet, there is something about hiring a virtuoso director who has far less experience in the musical genre. Steven Spielberg is a recent example, as his West Side Story was the first musical he ever directed, despite having one of the most varied and consequential filmographies in all of cinema. Despite this lack of experience in directing musicals, what he brings to West Side Story suits the material wonderfully. This isn’t to say that his adeptness at directing a musical is a huge revelation, considering his career-spanning mastery of film language combined with a recent knack for fine-tuned period pieces makes this a great match. Similarly, there have been plenty of other directors throughout the decades who weren’t exactly known for making musicals but were still able to bring something completely fresh and unique to the genre.

James Whale, Show Boat (1936)

As the director most famous for helming the likes of Frankenstein, Bride of Frankenstein, and The Invisible Man, James Whale was an odd choice to direct a lavish adaptation of Oscar Hammerstein’s groundbreaking Broadway musical. The film was also produced by Carl Laemmle Jr., who, along with Whale, helped to establish the gothic style and tone of the Universal Monster movies and by extension much of the horror genre as a whole. Though for all of the shadowy expressionism in Whale’s earlier work for Universal, there is also an unsung element of camp and dark comedy that doesn’t feel so incongruous with the musical genre.

Show Boat was famous for being the first integrated musical while tackling issues of race in a way that the stage musical hadn’t really done before. As you might imagine, not everything about Show Boat’s depictions of this topic holds up, though at the same time, the movie remains fascinating as a landmark in representation and what voices were given the freedom to be heard in the film musical. There’s no better example of this than when Whale’s camera turns away from the film’s white characters to focus on Paul Robeson, singing the iconic “Ol' Man River” while the film overlays images of him living in a post-Civil War South and changing the musical forever in the process.

Dorothy Arzner, Dance, Girl, Dance (1940)

Dorothy Arzner might not have quite the same name recognition as the other directors on this list, but as basically the lone woman filmmaker working in Hollywood during the ‘30s and ‘40s, her perspective on the musical is invaluable. Even more so when Dance, Girl, Dance paints such a female perspective on the act of performing that it’s nearly impossible to imagine a man directing it. The film is very much about “the male gaze,” as it follows two professional dancers (Maureen O’Hara and a pre-I Love Lucy Lucille Ball) in their various ups and downs in show business while having to contend with what men want out of them when they’re performing on-stage.

It’s hard to classify the film as a straight-up musical, as much like Arzner’s earlier films, Dance, Girl, Dance blends melodrama and comedy in a disarmingly modern way. Still, the film is very much a scathing critique of the musical, considering how much it focuses on what men are thinking and feeling when they watch women singing and dancing, whether it’s on the stage or screen. This culminates in one of the film's most memorable scenes, when O’Hara is expected to go up and dance onstage to the entertainment of fawning men but instead gives them a lecture essentially tearing them apart for being gross. Also, the fact that the musical numbers were informed by the choreography work of Arzner’s longtime partner Marion Morgan makes the film a fascinating ode to one of Hollywood’s first openly queer relationships on top of it being an essential early feminist work.

Howard Hawks, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953)

It’s hard to tell exactly why Howard Hawks wanted to direct a musical, other than that, after establishing himself as one of the great genre directors throughout the ’30s and ‘40s, the musical was one of the last big genres for him to conquer. In the book of interviews Hawks on Hawks, he reveals that he had no interest in directing any of Gentleman Prefer Blonde's musical sequences, leaving the directing duties for those scenes to choreographer Jack Cole. Which makes it all the more surprising that the film works as well as it does, especially with its fairly simple set-up of Jane Russell and Marilyn Monroe starring as a couple of friends/dancers who go on a trip aboard a ship while looking for love in vastly different ways.

Though the film is firmly entrenched in the rigid romantic norms of the 1950s, there’s still something incredibly refreshing about a film from this period about female friendship, particularly when Russell and Monroe play off each other so well. In their banter is where you get the Hawks touch, as his background in screwball comedies full of fast-talking dames makes him a perfect fit for the zippy nature of the musicals of this era. While Hawks’ camera is a little more utilitarian than the sweeping visuals of the MGM musicals like Singin’ In The Rain, the musical sequences (like the iconic “Diamonds Are a Girl's Best Friend”) are a joy due to the combination of gorgeous costumes, a brash use of technicolor, and Russell and Monroe being game for anything.

Brian De Palma, Phantom Of The Paradise (1974)

It’s hard to say if Brian De Palma spent the majority of his career working in the thriller and horror genres just because he felt most comfortable there, or if Phantom Of The Paradise kept him there. The rock musical was a both a critical and box-office failure, but it has gained a cult following in the years since for how distinctly strange it is. Anchored by the original music (and an unlikely leading role) from pop maestro Paul Williams, the movie is a glitzy riff on The Phantom Of The Opera about a disfigured songwriter who lives inside a theater owned by a benevolent record producer who — as the immortal tagline states — sold his soul for rock ’n’ roll.

Despite its lofty ambitions as a modern-day Faust or Dorian Gray (in addition to Phantom of the Opera) that seeks to satirize the music industry, the movie is perhaps best viewed as a wonderfully gaudy spectacle that would make a great double feature with The Rocky Horror Picture Show. De Palma’s success with his next film, Carrie, launched him into the stratosphere of great genre directors, and though De Palma would never direct anything this zany again, Phantom Of The Paradise still has plenty of the director’s trademarks. Though his films often have a kind of meticulousness that lends him to the obsession of many a movie nerd, he’s also prone to the kinds of bombastic flourishes (see John Cassavetes’ entire body exploding in The Fury) that make this such a cult-y delight.

John Landis, The Blues Brothers (1980)

For a period of time, John Landis was synonymous with a very particular kind of anti-authoritarian comedy that we now tend to associate with the 1980s. Landis combined this aesthetic with John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd’s SNL-born blues duo in a way that is a surprisingly loving ode to the soul and R&B music of the ‘60s as well as the city of Chicago. You’ve got some great performances from soul legends James Brown, Aretha Franklin, and Ray Charles, while Landis’s flair for the over-the-top sees every background extra shouting and dancing wildly in the kind of musical sequences that makes you wish you were there to revel in all the exuberance.

The over-the-top nature of these musical scenes also feels weirdly appropriate for the film’s multiple car chase scenes. Considering Belushi and Aykroyd’s Jake and Elwood spend most of the movie on the run from the police, the movie is this irreverent hybrid of musical and road movie. Appropriately, there’s something vaguely musical about the way Landis shoots his car chase scenes, where vehicles are crashing into each other from every direction in what could only be described as a ballet of destruction. Though Landis’s eventual exile from Hollywood was perhaps deserved (he was in charge the night three actors were killed on the set of Twilight Zone: The Movie), you still can’t help but marvel at the way he was able to make the big screen comedy into thrillingly orchestrated entertainment.

John Waters, Cry-Baby (1990)

After watching the parade of filth and debauchery that is Pink Flamingos, your first thought probably isn’t “Hmmm… could’ve used more singing and dancing”. But somehow, John Waters’ unlikely rise to relatively mainstream success after his earlier low-budget sleaze-fests led to him directing a Hollywood musical. Cry-Baby also makes a lot more sense when considering that it was the follow-up to Hairspray, a very film that's very musical despite not quite being one and which also indulges Waters’ fascination with the kitschier side of ‘50s/‘60s fashion and pop culture ephemera. That film was a surprise hit that tempered Waters’ more provocative instincts and, in the process, resulted in a studio bidding war over Cry-Baby, the first (and unfortunately last) time that would happen for any of Waters’ scripts.

Despite the number of musical sequences that make the director's high trash aesthetic a little more palatable, Cry-Baby is still pure Waters. The film’s plot revolves around a group of cool greasers known as “drapes” and their clashes against the squares inhabiting their little corner of 1950s Baltimore, before a scuffle between them sends the titular Cry-Baby (Johnny Depp) to jail. The whole straight society versus the weirdos feels like a perfect extension of Waters’ counter-cultural tendencies as well as his affinity for misfits. Meanwhile, the songs affectionately indulge the era’s doo-wop and early rock sounds, which often makes Cry-Baby feel like Grease’s snottier younger brother.

Mike Leigh, Topsy-Turvy (1999)

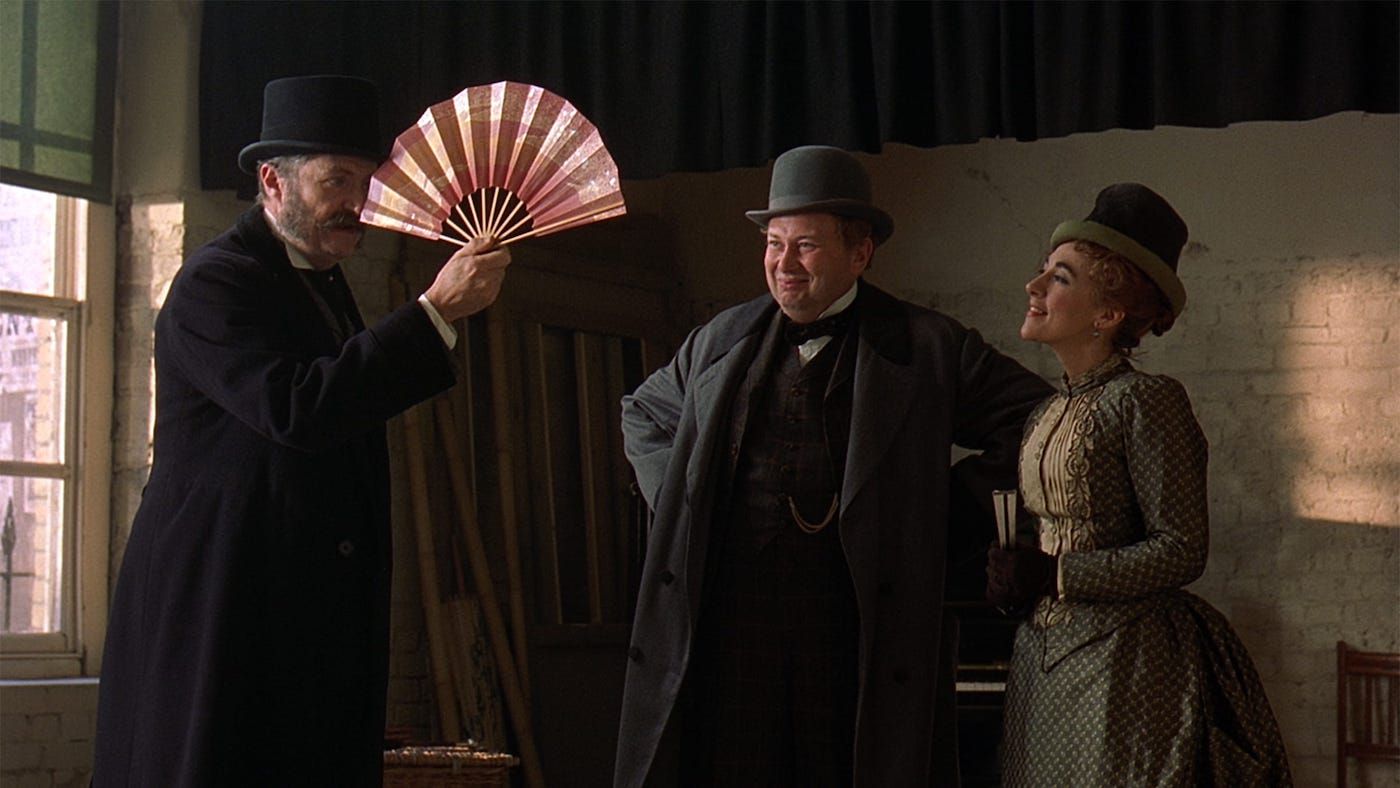

Known for his obsessively character-driven dramas, Mike Leigh might be the most unlikely person on this list to direct a musical. Though with Topsy-Turvy, Leigh tackled the musical in a very Mike Leigh way, where the film is less about the musical sequences themselves and more about the work that goes into making a musical really sing. The movie centers on the songwriting team Gilbert and Sullivan and a period that sees them struggling to top their earlier comic operas, which eventually leads to the conception of their most beloved stage musical, The Mikado.

There’s certainly a stuffiness factor to get over while watching the film, partly because Gilbert and Sullivan’s musicals feel a little detached from the modern musical, even if the film shows that there are some Victorian-era bangers in their arsenal. Additionally, Leigh goes out of his way to depict its late 19th-century time period in fine detail, featuring scenes of substandard dental care or characters struggling to use that new-fangled device, the telephone. Even though the film is more of an ensemble piece than you typically get from Leigh, it’s these details embedded within the film’s 160-minute run time that give each character a disarmingly lived-in feel. You could also look at Topsy-Turvy as an ensemble movie about creative ensembles, as it shows all the different actors and musicians and their various egos that go into making a musical.

Leos Carax, Annette (2021)

Another film where the director’s previous effort hinted at an interest in the musical, even if Leos Carax’s bonkers style of filmmaking doesn’t at first seem like the most natural fit for the genre. Holy Motors focuses on an actor jumping from character to character and in the process from genre to genre, one of them being the musical. With Annette, Carax commits himself solely to the musical, while still evoking a variety of tones and visuals that will occasionally lead you to question what the hell it is you’re watching exactly. It’s a musical that comes pretty late into Carax’s fairly sporadic filmography, which feels appropriate that it sees him collaborating with the band Sparks, who had been trying for decades to get a big-screen musical made.

Though it’s hard to call a film that goes in so many perplexing directions “perfect,” Annette nonetheless feels like a pretty perfect collaboration between these two creative forces with a taste for the absurd. On its surface, Annette doesn’t sound all that unusual, considering it’s a story of two famous people falling in love and having a child who one of them then harbors into show business. Though that doesn’t take into account that their child is a creepy marionette doll that stands among the most haunting cinematic inventions of 2021. While it’s debatable how much Annette works as drama, Carax’s striking imagery, Adam Driver’s intensely committed performance, and Sparks's songs make for a musical that’s hard to compare to anything else — which is something you'd only get from a director venturing into uncharted territory.