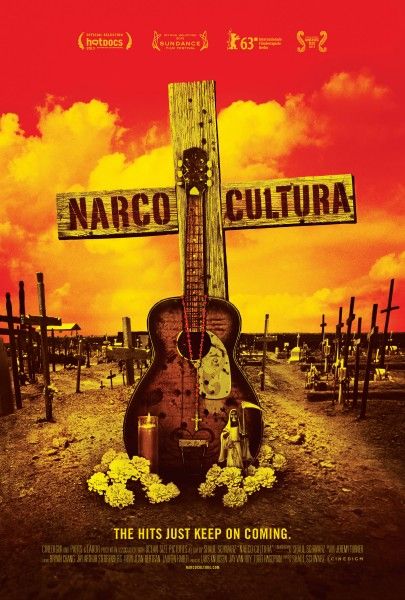

Directed and shot by veteran photojournalist Shaul Schwarz, Narco Cultura is a riveting look at the Mexican drug cartels’ pop culture influence on both sides of the border told from the perspectives of an LA-based narco corrido singer and a Juárez crime scene investigator on the front line of Mexico’s Drug War. The documentary film illuminates how, to a growing number of Mexicans and Latinos in the Americas, narco-traffickers have become iconic outlaws seen as a pathway out of the ghetto and glorified by musicians who praise their new models of fame and success.

In an exclusive interview, Schwarz talked about why the subject of conflicts and their effects on society has always appealed to him, what distinguishes his film from others that have examined the drug culture, how his experience as a war photographer influenced his vision and approach, how he gained trust from people whose lives are on the line to get to the heart of the story, and his thoughts on the narco cultura’s growing influence on both sides of the border. He also discussed his new production company, Real Peak Films, his role in Time Magazine’s new Red Border Films, and two film projects currently in development. Hit the jump to read the interview.

Can you talk a little about how this project came together for you and when did you decide this story should be told as a long-form documentary?

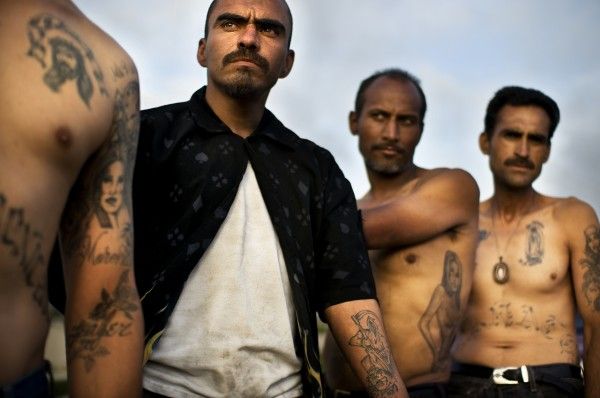

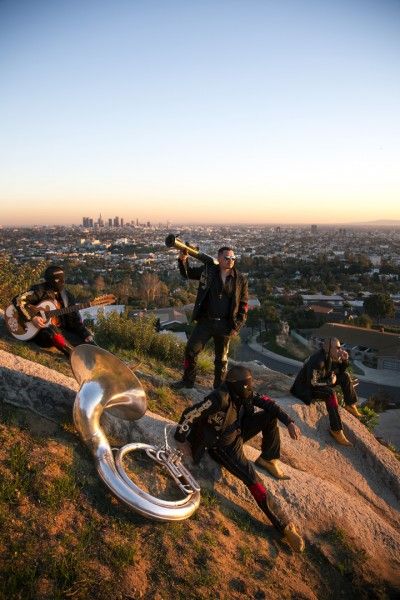

SHAUL SCHWARZ: I’m originally a photojournalist and I started photographing the Mexican-American Drug War in 2008. I’d always had an interest and covered many things in Mexico, and when this spun out of control, people called me to check it out, and I did and I was immediately glued to it. For two years, I just photographed it. I would photograph the violence particularly in Juárez but also elsewhere. As I got deeper into the story, I more and more stopped being just interested in the violence and the cartels, but more in how it reaches millions and millions and affects all of us through culture, through how it is in the hearts and minds, through music, through art. And the magazines, by the way, when I was photographing, I shot for Time and Newsweek and eventually I talked National Geographic Magazine into doing a little bit of a different story about the culture of it all. One day, in early 2010, I woke up in Tijuana during an assignment and photographed two murders, and that night I drove to Riverside, maybe like an hour away, and met Los Bukanas de Culiacan for the first time. That’s when it hit me. The contrast of literally not changing the smelly clothes from a murder scene to driving to a club where the singer parades around with a bazooka and everybody chants the lyrics to these crazy songs. It was just too overwhelming. But when I took those pictures and brought them back to my editors, they didn’t completely get it. They said, “Yeah, it looks like Halloween. It’s entertainment. Tarantino makes violent movies.” But, to me, it was all so connected. That feeling I had of how the deaths have exploded south of the border and how it’s glamorized north of the border, that’s what I wanted to capture, and I understood that that still picture just is not going to tell this story, and that’s when I decided to make this movie. I think that that juxtaposition really stuck through and is kind of the guiding light, if you will, for the film.

What is it about conflicts and their effects on society that appeal to you as an important subject to explore?

SCHWARZ: Unfortunately, conflicts have always been there and they don’t seem to be stopping. I’m a journalist and a photojournalist at heart, and I think that we have to be there always to cover it, and I’m certainly just one small number of that press corps. But something that is appealing is wars are terrible and ugly and hard and each conflict is different, but of every conflict I’ve ever gone to, I’ve also seen people being extraordinary in a good sense. It’s not just a black and white extreme situation that pushes people to extremes and they do crazy bad stuff. You also see crazy brave stuff. You see humanity in a different light. And so, as a story and as a journalist, I think conflicts are beyond the clarity of important to tell and be the whistleblower and not let people be killed without being noticed. They’re also just extraordinarily interesting and they’re more diverse than meets the eye quickly. So, for my career, and I don’t only cover conflict, but I always thought that these were the important ones. The most interesting thing is to go beyond the direct topic and say, “How does this affect the minds? What does this leave? What are the scars? What are the twists? What doors does it open to change?”

What do you feel distinguishes your film from others that have dealt with narco traffickers, the drug culture, and the Mexican-American Drug War?

SCHWARZ: Well, to me, there are a couple of very clear things. One is the style, the cinema verite, hard-hitting photojournalistic style. Most films on this subject because of the obvious access issue have been talking heads, experts behind desks for the most part, or a little bit of footage from this newsbreak or that newsbreak. My film has a unique access. It’s very raw. It doesn’t treat you. It doesn’t educate you. It really takes you through the lives of two individuals to see how the drug war feels, how it smells. You get a complete front seat. It’s like the old National Geographic slogan about photographers, “We take you further so you feel closer.” Something that was very key to me was my background going into this film and it’s extremely hard on this issue. So that is the first big thing.

And then, the second thing is the way we connect the dots, and the fact that this is not about just the cartels. It’s about the culture. It’s about the culture of fear. Even in our Juárez story on Richie Soto, it’s really a cultural thing to understand how he, to use his words, becomes part of the system. People just say Mexico is corrupt. Yes, it’s corrupt, but I wanted to show a good man that loves his country, loves his city, and how he struggles through trying to fight for it, but also how he ends up being part of the system by just being a bullet collector, by just filing files that don’t mean anything anymore because nobody is going to look at them. And that’s a culture of fear. That’s a culture where that is a product of that. So the way we juxtapose the glorification and the reality of the war is also unique for this film beyond its style. I’d say those are the two main things that are very different from other films.

How did you gain access while at the same time staying safe? How did you win trust from the people that you were working with in order to get to the heart of the story when in a very real sense lives are on the line?

SCHWARZ: The quick answer is: slowly and carefully. We did spend a lot of time and we had a lot of no goes. For every nine or ten murders we rolled out with Richie, we may have shot one or two. We hit a lot of brick walls. The key was getting the trust of our main subjects, and even that took a long time. Edgar Quintero signed on but he didn’t really sign on until years into the making. When I told him I wanted to film him interviewing a trafficker on how he writes the songs, he was just like, “Yeah, right. I’ll never do that with you.” And by the end of the movie, not only does he do our movie, but we go to Culiacan together and we actually spend time together on the other side, if you will. That is really the key to documentary filmmaking, at least in my book, and to good journalism as well. You access, access, access. In this case, it was being very honest about what we’re doing and creating borders of what we can’t do was very important. This was not an investigative. We do not open a file at the CSI and say, “Well how did this guy get murdered?” because if we would have done that, we would be dead and Richie would be dead. On the other side, with Edgar, there were also lines that we couldn’t cross. We got in very far because of our trust, but that was also because there were certain things, and we won’t go into too many details, that had to be left out. That was the delicate balance, both in capturing and taking risks. And then, we did get threatened, and we did leave in a hurry, and we did take extreme measures on the film. Particularly towards the end, it was extremely haunting. It was the same in the editing room. There are two, three, four scenes that I would love to share, but they would simply endanger people, and that was something we certainly did not want to get into.

You’ve been a war photographer and veteran photojournalist for more than two decades producing and creating content under fear and danger. Has your experience in the field been valuable in making this film?

SCHWARZ: Extremely. I mean, it’s literally in my DNA now. Again, that’s what we set out to do. We wanted this raw feeling. We always said we wanted to make you feel how it feels like. I don’t want you to understand the details. To feel how it feels, you just have to be on the ground with the people. That’s where photojournalists have a lot of magic. I think, from all forms of photojournalism, we are the ultimate surfers. We really do go further to make you feel closer. The trick was to change that into filmmaking because we have a visual sense and we have a great journalistic sense. We’re photojournalists, but you still have to make a good film and understand the art of filmmaking. I do believe, in general, that photojournalists adapting to documentary filmmaking would make outstanding filmmakers because of that access, not only because of their visual skills but more because of how willing they are to throw themselves so deep in the story. You always see that when you go to traditional conflicts. You see the TV reporters. You see the filmmakers. You see the written press. And then, the next level is always the photographers, that crazy one that just gets in and puts himself on the line, that hitchhikes to Haiti during the earthquake instead of waiting for a chartered plane. It is something that I’ve done for a long time and it is something I love to do. It’s so deep in my DNA that I don’t think I even question it anymore. I just do it. I love what I do. My mom loves it and is proud, but gets very scared and always asks me, “When are you going to make a film about flowers.” I guess it’s just so much in my DNA.

How has your cultural background and personal experience covering the Israel-Lebanon War and the Gaza Conflict influenced your vision and approach as a filmmaker?

SCHWARZ: To a degree, it’s also just about the experience of being in different places. But I think that covering a conflict that is personal, that influences your very own, your family, gives you some perspectives. As a journalist, when I fly in, I care about every place I go including conflicts, but the stakes are just different. In the Lebanon War, I remember that I walked around on the border photographing soldiers coloring their faces and walking across the border into this hell. And suddenly, out of the bushes walked my cousin who I didn’t even know was there. It just hits a note that is not your usual, and that is something I take with me and I try to be careful. Be careful, be careful, be careful. You can see how foreign journalists sometimes fly in and adrenalin’s kicking, and they mean well, but they dumb something down or take a quick side, and I try to be really careful with that. I try to understand that everything looks a little bit different from the perspective you look at. One day you could look at one side of the border and another day from the other side, and things just smell, see and look different although you might be staring at the same picture. That’s how we built complex reality and complex storytelling. So that’s one thing.

The other thing that’s more personal that kicks into play is that on most conflicts, Middle East or others, when you have a big hot story as a journalist, you will meet the same people to some degree. If I go to a typhoon that just happened or to an earthquake or to a war that just broke out, there usually are a couple of hotels of different fixtures, of different people, and it feels a little bit like we’re working together. When I went to Juárez, there was only local press. I literally landed in El Paso, mind you the safest city in the U.S. at that point, and walked across to perhaps the most dangerous place in the world at that time. That was a very stark reality, and the fact that I was there alone with some Mexican journalists who are so much more limited in what they can write because of their vulnerability. That’s how they could get killed so easily. It’s something that I try not to take lightly. I felt some kind of – I don’t want to sound cheesy in saying a mission – but at least some responsibility on my shoulder and I liked that. It definitely touched something that I felt. You know what? This counts. This time it’s important.

What are your thoughts on the narco cultura and its growing influence on both sides of the border?

SCHWARZ: When I first saw it, I was so angry because I spent two years seeing a country I loved being torn, and I blamed it, and I tried to understand how you literally could be dancing on the blood. But, as I lived in the culture for a couple of years, and I’m not going to defend it too much, but I also understood it. I understood where it comes from. It comes from the reality. It comes from things as simple as in the U.S. we call this thing the Mexican Drug War and not the Mexican-American Drug War. I think our policy has kept us pushing our head in the sand for way too long. And what this culture is, is a little bit more complex. They are chanting these songs, but who are the teenagers in that club when Edgar sings? I’d argue that 99 percent of them are just good old Latino kids working hard and trying to make a living and having a scene to hang out, some bad boy music scene to be a part of that right now seems to have become the pop culture. It’s not a good pop culture. My film wants to show they’ve got people in this culture and say, “Be careful. Look at this mirror because this is deeper in our hearts and minds, and this influences and this pushes kids to join cartels. They are not heroes and careful if you portray them as one.” What I did understand, and this is maybe the most important point, is it’s the reality that created the scene, not vice versa. Yes, the culture pushes the reality back, but it’s really the reality that creates this -- if there was not this cycle of death, if we didn’t let the bad guys win, if you will, with such a failed drug war and such a failed policy and continuing to stupidly say, “More guns, more money, a military solution is going to fix this,” instead of talking about it. It really is the policy that is so wrong to me, and when I spend time in it, I always get emotional and upset about it and that it creates this reality. To me, it’s the fact that teenagers these days, that a girl could tell me, “I’d love to date a narco. I’d love to marry one.” It’s not saying, “Whoa! She’s crazy,” because too many girls say that. It’s saying, “Holy shit! How did we get here? How did we get to this place where kids think that?” The answer is the policy, and it’s pretty much driven by an American policy and a Mexican policy, but first and foremost an American policy of pretending that this is far away, that this is not ours. It’s the Mexican Drug War. Well where does the $50 billion-a-year industry come from? Where do the guns come from? Where do the drugs go to? What about legalizing? What about talking about different solutions instead of just throwing money and guns at it? Without that, we wouldn’t be making this movie or talking about this reality. What I do think is this reality and this culture is not something to be taken lightly, because at the end of the day, there will always be crime and there will always be drugs. I don’t want to be naïve and I understand that we need to be serious to implement the law. I think the most important thing is always the next generation. If the next generation thinks El Chapo Guzmán is a Robin Hood, and if the next generation wants to marry a narco and doesn’t think it’s a cancer in Mexico and to some degree the U.S., we’re in trouble and we should think about how to, if not completely wipe that out, then at least change it.

Just to get a sense of the scope and complexity of the project, can you tell me how many days you shot, the amount of footage involved and your production process?

SCHWARZ: Again, in terms of time, the first three years were spent on still photography. We didn’t film, but it was obviously very, very useful to get the whole backdrop to the story. And then, we shot over the next three years. We basically shot from January 2010 and the movie premiered in January 2013. During those actual shooting days, it was somewhere between 130 and 150 days out in the field. And again, a lot of them were just sitting tight because a lot of it is a waiting game. There is a lot of that. And also, because of security, we didn’t want to be in there for long, so we’d go for a couple of days and then get the hell out frankly. So it took a lot of trips. In terms of hours of footage, we were actually quite precise. We shot somewhere around 100 to 120 hours by the time we left which for that amount of time I think we did fairly well. So that’s kind of the overall technical and I shot everything in 5D. We were always a two-man crew, me and my sound man and associate producer, Juan Bertrán, and we really stayed very minimal. That again was access stylized, one camera, no boom pole, no rigs on the camera, flat out 5D with just a viewfinder. We really crumbed it down and looked and felt very, very minimal and very quick and very run and gun style.

Is there anything you wish you’d known before you started shooting?

SCHWARZ: To be honest, looking back, if you know how to edit, you’re like, “Oh! I didn’t have to go on that trip.” But you can’t know that, and because I did shoot for two years intensely as a still photographer, the quick answer is no. I knew a lot and I actually knew what I wanted to do in the film when I started filming because I’d already spent so much time [researching it]. In a way, it was such an intense research for the stills and doing so many magazines stories that when the film started I was already burning to tell the specific story we ended up telling. Of course, the reality is we took tons of trips and tons of scenes didn’t make it, but I wouldn’t change that. It was part of the process.

What did you learn about yourself in the process of making this film?

SCHWARZ: It’s always harder than you think to make a good film. Feature films are a hell of a marathon to say the least. It’s kind of your endurance. How much can I push? How much do I care? How much time it takes is a nice reminder. I saw a lot of colleagues that did three films while I was making one. But I think now I’m happy and proud of that. It’s just the nature of it. This is a hard, hard film. It’s harder than it looks to infiltrate this world.

What are you working on next?

SCHWARZ: Two main things. One, I started a production company called Real Peak Films for people like me, photojournalists and photographers moving into film. I do believe we have a special talent. We keep it very raw. I’m working with photojournalists and particularly with a new branch of Time Magazine. Time Magazine has launched a new film department called Red Border Films and I’m an executive producer. We have three executive producers on that. We’re doing a lot of online shorts and remaking the brand of Time Magazine into a film department. So that’s an ongoing, long term project.

The second thing is a very, very different film that I’m directing with my brother about a family story that happens between [inaudible] and Canada about an uncle I have who at the age of 68 learns that he was an adopted child. He learned just a month ago that he actually always had a brother and a father which he didn’t know of. So, a very different film, and yes, my mom is pleased with me. (Laughs) I’m also researching a similar, edgy subject that I plan to start sometime next year which will be the trafficking of animals and poaching out of Africa. Trafficking seems to have become more in my DNA.

I am done with Mexico for a while, both because I’m tired and I think it’s time to pass the torch to others. After five years, it’s just so much that I want to move on from this Mexico story and because I’m banning myself on a safety level for a while. I gave this film so much. I hope people buy tickets. My only wish is that people really go out there to theaters. I think people were very skeptical always when they said, “Oh docs, they don’t work. When you make depressing docs that don’t have ‘save this or save that,’ they just can’t do well.” I fought very hard to say, “No. This is important. I think people care and I think it’s interesting.” I hope people go see it.

Narco Cultura opens in limited release this weekend.