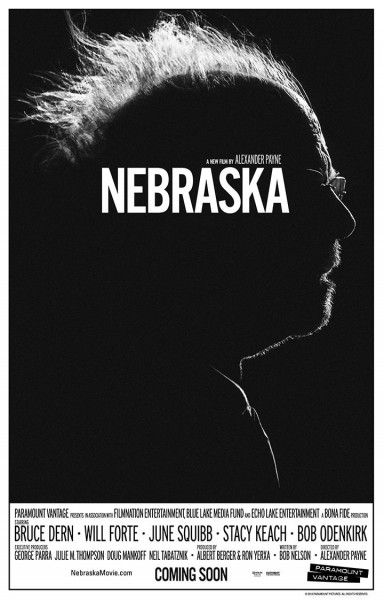

In the past, I’ve made jokes about how progress on social issues is inevitable because the people holding antiquated values will die off soon. Nebraska made me feel a little guilty about those jokes. I don’t feel guilty because I’ve come to agree with their discriminatory viewpoints, and the movie doesn’t address those kinds of attitudes associated with the red-state heartland. I feel guilty because I’ve been so casual with the lives of old people who probably never had much to begin with. With his newest film, director Alexander Payne has created a deeply compassionate picture of elderly life, social decay, economic immobility, and put it into a moving father-son road trip story. Anchored by strong performances from Bruce Dern, Will Forte, and June Squibb, Nebraska is funny and touching quest to find the good life at the end of life.

Woody Grant (Dern) believes he’s won a million dollars in a sweepstakes, and he’s determined to go to sweepstakes headquarters in Lincoln, Nebraska to claim his prize. His wife Kate (Squibb) and sons David (Forte) and Ross (Bob Odenkirk) try to explain the sweepstakes is a scam, but Woody won’t be deterred, and since he can’t drive, he’s determined to walk all the way if he has to. Despite feeling some residual resentment towards his alcoholic father, David agrees to drive his dad from their home in Billings, Montana to Lincoln. The two make a stopover in Woody’s hometown of Hawthorne, and the town’s residents begin to hover when they believe Woody is a soon-to-be-millionaire.

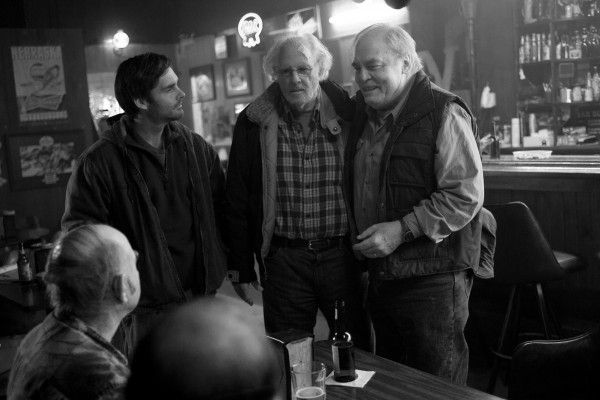

Hawthorne is filled almost entirely with elderly residents, or at least they’re the most visible people. Aside from a kid photographer who comes to take Woody’s photo for the local newspaper, the youngest residents are David’s jerk cousins. The cousins are interested in the money along with some of the other townsfolk, most notably Woody’s old partner, Ed Pegram (Stacy Keach), who believes he’s owed the money for past “support”. But not everyone in town is a vulture and that Woody is their meal ticket. Most of the residents are just happy for him and happy that someone from their desolate, dying town has found good fortune.

The town of Hawthorne has been left behind by America. The parents were tethered to farming jobs and other menial work, and the kids have all probably moved away. It’s almost a ghost town with plenty of ghosts already floating around such as Woody’s parents along with some of his siblings and friends. What’s left is people who are pleasant enough. They drink at the local bar; they take afternoon naps on the couch; and quietly gather around the TV for Sunday afternoon football.

It’s not a romanticized version of small town America. These are people with small, simple lives and those lives are never going to change. They’re too old, and Payne acknowledges their stasis before the movie begins by putting up the old Paramount logo, and filming the movie in black-and-white. Modernity has been removed from the picture. Woody’s “fortune” is so uplifting for them because it’s someone they know and identify with even though they haven’t seen him in decades. David recognizes this need for something more even if it just a fantasy. Woody is in the early stages of dementia and he may not have much time left, so David pleads with his mother to let his father just have the dream even if it’s only for a few days.

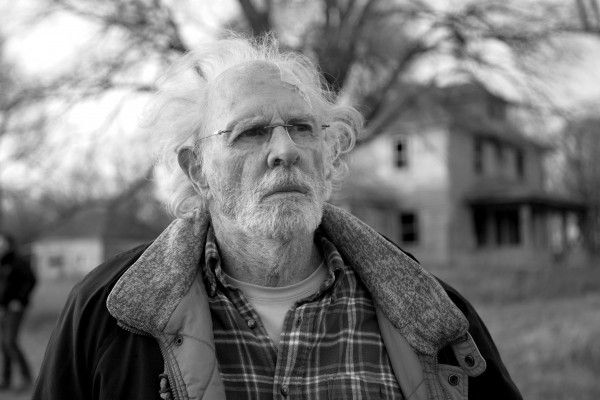

Payne rewardingly unfolds his film by gradually showing new facets of his characters. Early in the film, we see Woody criticized by his family for being neglectful, a fool, and a drunk. He’s not a coot or an ornery old man. Dern plays Woody with a great deal of quiet sadness. He’s constantly staring off into the distance or dozing off. Part of it is the old age, but part of it is a need to escape. He doesn’t hate his family, and despite their resentment, especially from Kate, they don’t hate him either. They’re frustrated, and perhaps they’re frustrated with more than just Woody’s behavior. As life progresses, options become fewer and fewer, and those options dwindle even further when the economy tanks. David is already seeing his life dry up. He works at a speaker store and been dumped by his girlfriend.

Forte’s kind and gentle performance is the tether all audiences can have to the elderly characters. Traveling with his father and spending time in Hawthorne, David gets a look at a future he doesn’t want, but he’s not raging against either. He’s concerned—both about his own prospects and for his father. David is a good son almost to the point of where his actions are difficult to believe when we consider his father’s past behavior. Like Dern, Forte gives a restrained performance and matches his veteran co-star in temperament and tone. These aren’t big performances full of big, cathartic emotions. It’s a relationship of patience and tolerance, which in some ways is more rewarding than weeping and wailing.

The “loudest” performance comes from Squibb, and it’s almost unbearable until we begin to have a better understanding of Kate’s relationship with Woody. As I said, the movie is about a slow, gradual reveal of the character’s lives and what they mean to each other. Kate’s insults towards Woody are so vicious, and they’re made even more hurtful by his refusal to respond. She seems like a particularly vindictive woman not only towards Woody, but also towards her old acquaintances in Hawthorne whether they’re living or dead. But Squibb’s comic timing and ferocity are a powerful counterbalance that never overwhelms the movie. As the story progresses, we begin to reevaluate her character just as David and the audience comes to reevaluate Woody and the people of Hawthorne.

Payne has painted a beautiful, emotionally moving picture by using small touches. Phedon Papamichael’s cinematography is more than gorgeous—it’s thoughtful. Rather than indulge in the all the beautiful shots black-and-white photography can provide, he wisely chooses to make daily life in Hawthorne look plain and unglamorous. But then in the private moments between the Grant family, especially between Woody and David, Papamichael will provide some stunning shots that make uses of the rich contrast between night and the few lights sources of Hawthorne’s main street. Mark Orton’s score follows suit by using subtle instrumentation consisting of guitars, a violin, a piano, and an occasional trumpet, but then, when necessary, can build to something surprisingly stirring. Payne always finds a way to be effective without resorting to shouting or shoving his audience towards emotional moments.

I’ve lived in cities for almost my entire life, and it’s easy to brush off the people in the heartland as political enemies or backwards hayseeds. Nebraska ignores the surface differences, and finds something far more captivating by showing the need for more when there’s not much left in life. When a restaurant full of people in Hawthorne applauds Woody for his good fortune, we see that this may be the first time he’s ever had respect and recognition. It’s such a simple moment, but it’s incredibly memorable, particularly in the scope of his whole life. Nebraska is filled with these kinds of moments where a small triumph or a big laugh or an emotional bond comes along unexpectedly and makes the movie even richer. For Woody Grant, Nebraska is the Promised Land where even the welcome sign reads “The Good Life”, and although there may not be a million dollars at the end of the journey, the promise of a better tomorrow is exceptionally moving when there aren’t too many tomorrows left.

Rating: A-