[NOTE: This is a re-post of our review from the Telluride Film Festival; Neruda opens in select cities this weekend; it is also Chile's official submission for Best Foreign Language Film for the Oscars]

Chile's Pablo Larrain (Jackie) is one of the most intriguing directors working today. His films have confronted many of Chile's past and current shames instead of sweeping them under the rug after celebrating Pinochet's ousting. Larrain is a filmmaker attempting to stop history from repeating itself, but he's also pretty rebellious with how he handles his imagery. His largest mainstream success thus far, No, was shot digitally to be as grainy as possible, so as to directly match the TV news programs and advertisements that aired during a time where VHS tapes where used to broadcast pre-recorded material. And thus Larrain could use existing footage from the national plebliscite and also seamlessly recreate footage with important 1988 Pinochet-oppositional professionals intercut with the star of that film, Gael Garcia Bernal. His films generally possess a texture that further illuminates his film's text. And his latest applies a new texture to the staid biopic template.

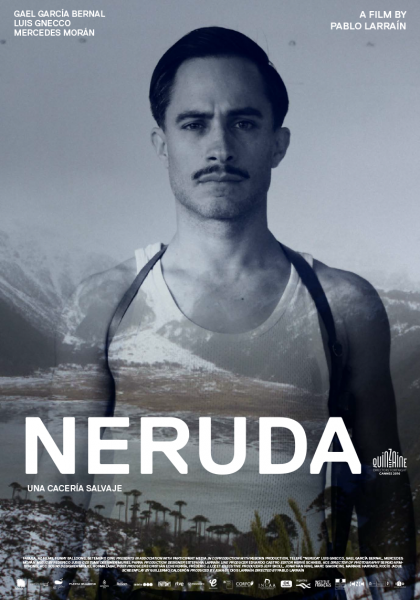

It should come as no surprise that Larrain and his cinematographer, Sergio Armstrong, came to Neruda with a unique color palette prepared. But what is surprising about Neruda is how far it strays from being a biopic about the famed Chilean poet and Communist Senator. What begins as a Pink Panther-esque cat and mouse chase takes a distinct shift midway into an exciting and uncharted Jacques Rivette territory, where what's real and what's imagined and which real people can interact with imagined people begins to unfold. The second half is so strong—and beautifully reveals the film to be about the pulpy desires of a man beloved for his enthralling words of sexual seduction—that you end up wishing the anti-biopic shift started sooner.

Luis Gnecco stars as Neruda in 1948. The poet is shown reciting his love poem greatest hits in a series of bacchanal events with both elites and prostitutes. At this time, he's not published anything new in a while, and serves as a Communist Senator in Chile. He is ordered to be arrested when the Chilean President outlaws Communism, and Neruda and his wife (Mercedes Moran) shuffle between various elite safe houses, while the government plasters poster propaganda that declares him a traitor to the country.

Garcia Bernal rejoins forces with Larrain here, starring as a goofy police investigator who shares the last name of a former Director of Police Investigations because that agent impregnated his prostitute mother and he fought to keep that name, despite the Director's denials of parentage. Oscar (Garcia Bernal) seems extremely unskilled and frequently notes humorous asides in narration, sometimes even responding to things being said in the various safe houses where Neruda resides. This call and response between the hunter and the hunter begins to show a shared conscious state between both men. Neruda leaves Oscar notes in pulp fiction books and Oscar, despite lacking any obvious detective skills, seems to always be in the exact place that Neruda is at, but looking in the wrong direction. This cat is always extremely close to the mouse.

Larrain and Armstrong shoot the first half of the film like 1950s postcards, sepia-toned and over-saturated, with many lens flares entering the frame from sunlight, reminding you that a camera is recording these events. It's a filtered documentary approach for the first half but it gives way to a crisp and grandiose wide shots when Oscar begins chasing Neruda through the snowy Andes via motorcycle and horseback.

As mentioned prior, the first half of this chase is given a near-slapstick approach, as an elegant mind outwits a dimwit as Neruda frequents brothels when he should be under lock and key. This section is nicely shot and features a magnificent scene where Oscar "interrogates" a transvestite brothel singer. Mostly, Oscar just listens to the immense love and respect that the man has for Neruda. You sense that Oscar has immense respect for Neruda, too, but his stronger desire is to live up to his bastard father's name and bring in the poet. But this section is also frustrating because Garcia Bernal is given so little to do other than narrate, look befuddled, and read the pages of the pulpy novels that Neruda has left for him.

Garcia Bernal gains freedom and agency by the second half. And this is when the comedy-noir schtick begins to give way to another dime store novel template: a western. The mountains, snowfall, and horseback riding push this section into a glorious and grand chase. The method in which Oscar begins to take hold of the reins of the narrative is something that's deliciously sly in Guillermo Calderon's script, but it should be kept secret in a review. Needless to say, it pushes Neruda into a narrative territory that's completely devoid of facts and instead dissects the relationship between a detective and a suspect, not in professional terms, but in how it's novelized by someone who generally has no experience in the field. There's still some slight comedic strokes in the mountain range, but as Oscar develops more detective instincts, the scope of Neruda broadens into a vastly creative canvas. And the lens flare and documentary approach gives way to splendid cinemascope vistas.

Neruda is a very deceptive film. It keeps its cards close to its chest for half its run time— even folding on occasion—before revealing a Royal Flush. When the narrative shifts into non-biopic territory, Neruda is still somehow able to reveal the soul of a poet, give new life to a detective, comment on the lunacy of the Chilean government at the time, and play in genres that a writer of odes might have always wished to have done, but didn't. Beginning to end, this might not be Larrain's best film, but it certainly inspires the most awe for his rebellious tendencies.

Grade: B+

Neruda plays in select US theaters on December 16, 2016.