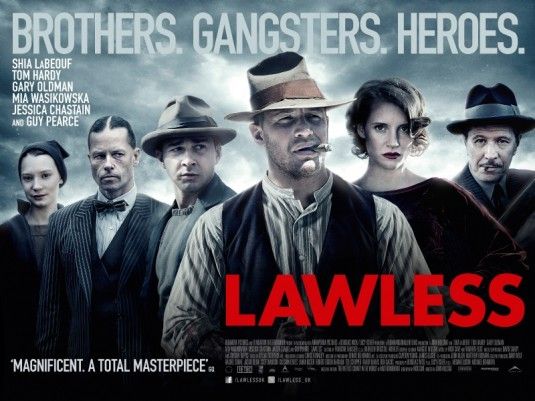

Lawless – adapted from author Matt Bondurant’s fictionalized account of his family, The Wettest County in the World – tells the story of the infamous Bondurant Brothers, three bootlegging siblings in Prohibition-era Virginia. Forrest (Tom Hardy), Howard (Jason Clarke) and Jack (Shia LaBeouf) are entrepreneurs with a thriving local moonshine business, until corrupt and lethal Special Deputy Charlie Rakes (Guy Pearce) shows up from Chicago to take a piece of what the brothers have built, threatening everything that they represent. Directed by John Hillcoat and written by Nick Cave, the film also stars Gary Oldman, Jessica Chastain, Mia Wasikowska and Dane DeHaan.

At the film’s press day, Collider got the opportunity to participate in a roundtable and 1-on-1 interview with screenwriter/music composer Nick Cave, in which he talked about how he ended up as the screenwriter on Lawless, what led him to transition into writing films, how he’s always been a visual writer regardless of the medium, making the villain more flashy for Guy Pearce, collaborating with the actors for 10 days prior to shooting, how his scoring collaboration with Warren Ellis works, detaching from the script to enjoy the finished product, how the original cut was about three hours long, and his reluctant cameo in the film. He also talked about being more interested in collaborating with John Hillcoat than with being a screenwriter for hire, the possibility that he could produce and compose the soundtrack for Guillermo del Toro’s stop-motion Pinocchio, and what happened to The Threepenny Opera that he met with Andy Serkis about doing. Check out what he had to say after the jump.

Question: When director John Hillcoat first came to you about adapting The Wettest County in the World, were you hesitant about it?

NICK CAVE: Yeah, me and John landed at the same time, actually. Doug Wick and Lucy Fisher, the producers, wanted us to do it as a team. So, it was something that we discussed together. We were like, “Do you want to do it?” “I don’t know. Do you want to do it?” “Well, I’ll do it, if you do it.” We were really looking for the next film to do. I had written this other screenplay for him, in between, which I’d turned into a novel called The Death of Bunny Munro, and we loved that one, but we were looking to do another one that would get made. And then, this came along.

Your music has always really stood out as telling stories that are so visually easy to see. Did that make the transition to screenwriting more natural? Had you ever thought about it before collaborating with John Hillcoat?

CAVE: No, I’d never thought about it. The way it happened was that I’d been complaining about John’s scripts for a long time ‘cause he would get me to read them. He was trying to get this Australian western off the ground, and there were a few scripts written. In the end, I said, “This is no good, this script,” and he said, “Well, you write one then.” I went, “All right, I will!” I said, “I’ll just give you a story and you get someone to do the dialogue. I don’t want to do that. I can’t do all that sort of stuff.” And then, I just started writing the story and I thought, “Oh, I’ll throw in a bit of dialogue,” and I ended up writing the script. I just enjoyed doing it. But, sure, it’s from writing narrative songs. That’s what I do. I’m a storyteller. I always have been. Somehow, I ended up in music, but probably should have ended up somewhere else, actually, where the storytelling is more effective. It’s a pain in the ass in songs because you have to listen to the narrative when all you want to do is just listen to a piece of music. So, writing scripts is more of a natural thing for me to do, but it’s not what I want to do. I want to be a musician.

Do you just naturally write so visually?

CAVE: What it’s all about for me is what you see. That’s just the way I look at the world, and the way I write. For my musician friends, it’s all about what you hear. I know when I sit with my band members and we’re playing back a song that we’ve done, I know that they’re experiencing it in a completely different way and hearing stuff that they’re alerted to because the way the interpret the world is through their ears. Mine is through my eyes.

How challenging was it for you to take such an American story and adapt it for film?

CAVE: As with all great books, the last thing you want to be is the guy who fucked up the Matt Bondurant book. I was more worried about that than I was worried about getting the Bondurant’s right. I always saw the Bondurant story as a myth, so I didn’t feel that much of a problem about pushing a little further into the myth and playing around with the actual events. But, I felt that I needed to remain respectful of Matt’s talents as a writer and his descriptive talents and his talents at writing great dialogue. It was easy to write, in a way, ‘cause all that stuff was there in the book. The dialogue is incredible. It’s to die for. I could just take these great things that everyone said and take all the credit for it.

Because this is a fictionalized version of the Bondurant family, did you also look at the actual history, of that time?

CAVE: Yeah, I did as much research as I needed to do. John does huge amounts of research. He piles up the research. He constantly fed images, every day, in your emails. He’d say, “Read this and read that,” not that I really did a lot of that reading. The book itself is so rich in detail that I didn’t need to do a lot, to be honest.

Having worked with Guy Pearce before, did you write his character with him in mind?

CAVE: Guy [Pearce] is one of John and my real favorite actors. We loved him way back before we could get him in The Proposition. And we sent him Lawless and said, “Would you play the villain?,” and he came back saying, “Yes, but I want that villain to be memorable.” The villain that was actually there was the Rakes in the book, who was a nasty country cop, and it was a smaller part. I happened to be in Melbourne, at the time, where Guy lives, and we were able to talk a lot about that particular character. We changed it and developed it and made it a more interesting character to play. There’s the sexuality of Rakes, and the fact that he’s a city guy who’s come down from Chicago. That was all fiction, in order to lure Guy Pearce into the role. And then, one day, he sent a picture of his hair shaved down the middle and his eyebrows shaved off, and he said, “What about this for a look?” My 12-year-old kids picked up the phone and looked at it. We have a thing, every Friday night, with my 12-year-olds, where we watch an inappropriate movie together. It’s part of our bonding experience. But, they saw that picture of Guy and couldn’t eat for two days. It’s a great hairstyle, though.

What was it like to collaborate with the cast, once all of the actors were in place?

CAVE: You’re not just collaborating with the cast. You’re collaborating with people you don’t even know, when you’re making a film. You’re collaborating with people you’ve never seen. It’s just a name coming down the way saying, “Mike Harris doesn’t like this scene,” and you’re like, “Okay, I don’t know who the fuck Mike Harris is, but I’ll change it.” So, the collaborative process is very, very different than when you’re collaborating on a record with the musicians you’ve worked with all your life. But, there was a lot of collaboration that went on with the actors.

Once the film was shooting, did the script continue to change?

CAVE: I had 10 days with the actors, before the principal shooting started, and a lot of stuff got moved around, in that time. But, the last day I was there, which was the day before they started, I was like, “All right, I’m shutting the script down now.” John was there, and I said, “Does anyone have any little things ‘cause when it comes to doing it, tomorrow and for the next few weeks, there’s no changes. We don’t want that sort of situation.” But, in that 10 days time, we could look at anything. Some actors were very much like, “I joined on because I loved the words, and this is what I’m going to say.” Shia [LaBeouf] and Dane [DeHaan] were like that. Jason Clarke, who played the middle brother, had a really unique approach where he would not say anything that was in the script when he rehearsed.” I said, “Well, hang on, are you ever going to say what’s on the page?” He said, “No, I’m gonna say that when we actually film. I don’t want to rehearse the lines I’ve gotta say when we film.” That was odd and disconcerting, at the time, but he was amazing and followed the script very closely. Tom [Hardy] wanted to look at everything and every line. That was more of a negotiation.

What is it about screenwriting that sets it apart from the satisfaction you get from writing songs?

CAVE: Well, songwriting is really difficult for me. I write my songs in what I call my office, but it’s a room. I go in there every morning at 9 o’clock and I come out at 6 o’clock, and I just work on writing lyrics. I do that for a six-month period of time, to try to get an album together. And it’s very lonely and isolated and painful. There’s a lot of that classic creative agonizing that goes on, in that situation. Writing a script is something that’s completely different. It’s very much a collaboration. You’re sitting around with other people and you’re talking together about how things can be done, and you can collaborate on a story like that, whereas you just can’t collaborate on a lyric. A lyric is a much more personal, abstract thing. And so, when you collaborate, you don’t have the same doubts. You say, “How about this?,” and everyone goes, “Yeah!,” and then you write it. When you write a line in a song, you think, “How’s this?,” and all you’ve got is your own mind saying, “It’s rubbish! It’s shit! It’s going to be terrible!” That’s what you’re battling, all the time. It’s actually a pleasure, and it’s relatively easy, to write a script.

When you’re writing the script and composing the music, does one come before the other or do you write them together?

CAVE: I was writing a script, but also knowing that I was gonna do the music and talking to John a lot about the music. And we knew, early on, that we were going to have songs in this film. So, I was writing scenes thinking, “We need a scene that’s long enough to put a significant amount of song into this particular scenes.” I was deliberately writing scenes that were stretched, so that we could put music into it. The last thing I wanted, if we were going to use songs, was to have tiny snatches of songs ‘cause that’s just distracting and irritating, on every level. So, we were deliberately thinking about that. There were long descriptive passages put into certain scenes, which were stretched, in order to get a decent amount of song in there. But, the way it’s filmed has nothing to do with me. I know that John has a lyrical way about the way that he films, and I know he’s very much interested in violence, and the ramifications and reverberations of a violent act through a story. That’s one of his things. If you look at all his films, they’re all like that. Part of that lyricism is to confront you with beauty and to lull you in that way, so that he can hit you suddenly with a piece of violence, and then lull you back down into it again. That’s the way I’ve always written, and I write songs in that way, too. I guess that’s why he likes the way I write, and why I like the way he directs.

How does your collaboration with Warren Ellis work?

CAVE: The way Warren and I do scores is that largely the music is written while we’re doing the score. We’ll have some little ideas, but largely we just sit in the studio and make it up, as we go along. People hate that. They really hate that. There’s all these strange guys in the studio, with dark shades and ear pieces on, who go, “I don’t know what they’re doing now.”

Is it weird for you to see the finished project? Can you detach from it enough to actually enjoy it, as an audience member?

CAVE: Initially, there’s always things that you think, “ I wish they hadn’t have gotten rid of that.” But largely, the edits that were done, I think made a better film, in the end. There were some things I wish they had left in, but just because I wish they had been left in doesn’t mean that, if they had been left in, they would have made it a better film. They were just scenes that I thought were really cool. It was three hours long, or something, when it first got assembled, so it had to be cut. I’m not precious about the stuff at all, but it is weird. The things that usually get cut are the things that aren’t pushing the story, and it’s actually those things that, as a writer, you’re more interested in, like the peripheral details and the atmospherics, and how nature might be echoing the human drama. That stuff gets weeded out pretty quickly. All artistry and originality is the first thing to go. No, I don’t mean that.

Were there any specific scenes that you hope will be on the DVD?

CAVE: Really, I’m not sitting here, as a screenwriter, complaining about the edits. I’m not. The film works great. I guess the only edits that really worry me are edits that are done because someone somewhere down the line thinks I’ve been offensive. They are the ones that piss me off, when they get edited, like when it’s too long of a piece of sustained violence or something. That always feels, to me, like it’s pandering to the taste of the audience, and that can piss you off.

Since you have inappropriate movie night with them, have your kids seen this movie?

CAVE: They’re in it! It goes to a Chicago scene, in the montage in the very beginning, and there’s a dead gangster with bullet holes in his face, which is me. And there’s a couple little kids who pick up a Tommy gun and look down at me, and those are my kids. They were like, “Gee, dad, you look great!”

Whose idea was it to put you in the movie?

CAVE: It was John’s, actually. He suggested that. It wasn’t my idea. The idea of acting is something that absolutely repulses me. I just can’t do it. I’m terrible at it. I get roped into films, every now and then, and it’s always a disaster.

Because you have such a great collaborative relationship with John Hillcoat, does it make you nervous when other filmmakers approach you about working with them?

CAVE: Yeah, actually. It’s weird. The thing is that I’m not that interested in being a screenwriter, but I am interested in working with John. But, I do get loads of people asking, these days. On one level, you think, “Well, do I want to write a script for someone whose films I don’t really know, or whose films I don’t really like, just ‘cause it’s a job?” It really depends on who’s asking, I guess.

Guillermo del Toro has said that he’s interested in having you produce and compose the soundtrack for Pinocchio. Is that something you’d be interested in doing?

CAVE: We’ll have to see how that goes, but the story is amazing. Everything has changed around, but if it’s the same script and he’s doing it, then yeah, of course.

There was talk that you and Andy Serkis were working on bringing The Threepenny Opera to the screen again. What happened with that?

CAVE: I don’t know about that one. I know we had a meeting. It’s amazing how these things get around, but we did have a meeting. I don’t know if anything happened. There’s a million of these ideas running around out there, that people are trying to get to happen. It’s kind of a miracle that anything ever gets made, really.

How do you find the one that’s going to be worth your time?

CAVE: Well, scriptwriting is not my main job, so I can just work on things that I want to work on and that look like they might get made.