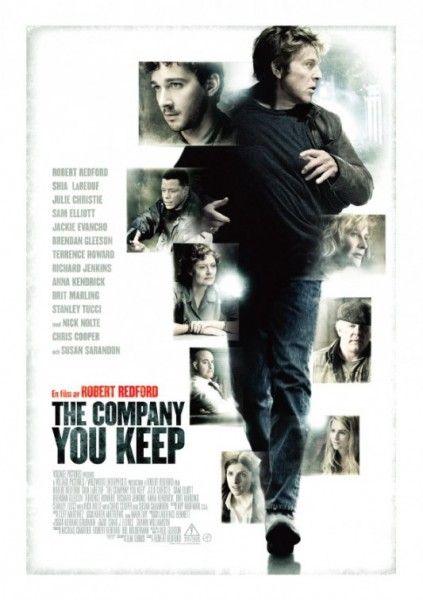

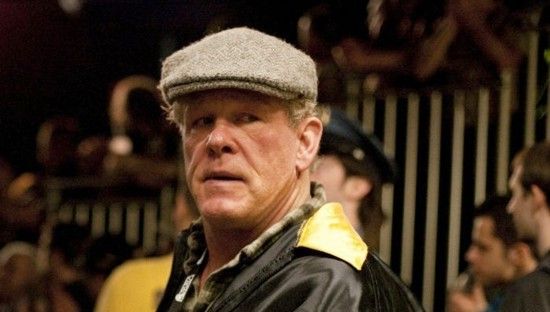

With a 40-year career in Hollywood that’s still going strong, three-time Academy Award nominee Nick Nolte continues to be drawn to diverse and challenging roles, so it’s no surprise to find the Omaha native playing yet another pivotal character in Robert Redford’s political thriller, The Company You Keep. Set in the present day, the film recalls the history and aftermath of the radical anti-war protest movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s, and one of its more violent manifestations, The Weather Underground.

In a wide ranging interview at the film’s recent press day, Nolte talked about working with Redford on location in Vancouver, his thoughts on the Weather Underground, how his childhood experiences turned him against war, why he has faith in the younger generation’s ability to navigate today’s world, and how he believes there will always be change and resistance to change and that every generation will be challenged morally at least once in their life. He also discussed his early work in regional theater, how he met his first wife and wound up doing LSD in the desert, why he likes chanting with Hare Krishnas and felt it was important to reconcile with Martin Scorsese. Read the interview after the jump.

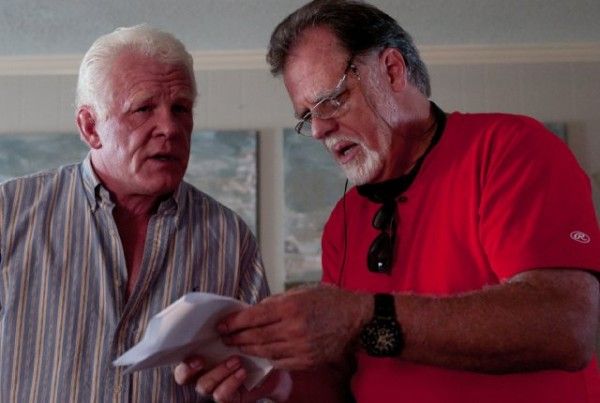

Question: Can you talk about working with Robert Redford? What was it like being directed by him and acting opposite him?

Nick Nolte: Well, I was curious, very curious, about how Bob worked, and I always am when it’s a director-actor. I like working with writer-directors because you can solve problems right there. I felt no tension from Bob at all in rehearsals or in discussing it. There just wasn’t any tension. When I was called to go on up to Vancouver and went up, it went smoothly and everything was fine. And then, we broke for lunch. I went to lunch, and on my way back from lunch, I heard them say, “Roll ‘em!” and I looked down and there was Bob running down the alley. He had gotten paranoid at Donald’s place (Nolte is referring to his character) and thought he had called the FBI. I went in there and said, “Wait, wait, wait a minute. I’m supposed to be driving that car.” And then, all of a sudden, Bob disappeared and the producer wasn’t there. There was just three big guys standing in front of me, and they said, “Do you have a problem, Mr. Nolte?” I thought about it for a second and I said, “No, I really don’t,” because I realized that Bob was going to run that alley, and he only wanted to run it once, and he didn’t want the actor to fuck up the mark and have to run it twice. He’s 75, you know. We tease each other a bit about how many squats can you do and stuff like that.

You might know how difficult it gets in life, and they don’t build things [to accommodate that]. This hotel is awful. I mean, the toilets are so damn low that you damn near can’t get up. It’s just wild. I know what happened. They calculated it. They took the world average of height including all the races, and it comes out to being probably about 5 foot. So it doesn’t work for us. That’s all. It’s tough. It really is tough if you’ve got any damaged cartilage in your knees. If you’re an American boy, you’ve probably played some athletics and failed somewhere along the line, as Pete Champ would say. All American males are failed athletes, and it was big time even if it was Little League. It meant a lot to you. God bless them. But they should do something about the tubs. You can’t get into those tubs and they don’t cover you up. Do you think the hotel owners really think, “God, I’ll save money on these tubs”? Do you think they think about how much water they’re gonna save to make their clientele uncomfortable because they’re going to save two dollars in water? It’s crazy thinking.

What’s your take on the Weather Underground and their opposition to the Vietnam War?

Nolte: When I was a kid, my Dad went to World War II. I didn’t know him. I was born in ’41. We were in Ames, Iowa and not in the college part. We lived in this three-story Victorian house. It looked grand, but a lot of it was rented out. I remember a day when there was a lot of excitement because my Dad was coming home. I didn’t quite know what that meant, but I can remember the feeling of excitement, and then, I remember the image in the doorway which was a skeleton. He was just a skeleton. He was 6 foot 6 and I don’t know what he weighed. He must have been only 140 pounds. They took him upstairs. And then, every day for a little time, I had to go up and sit in the rocking chair beside this skeleton that would just be struggling to breathe. It occurred to me that whatever he went through, I didn’t ever want to do it. That was it. That’s where the idea sprung. I don’t want to be involved in that. Then it goes onto I don’t want to kill anybody. I can’t do that. I just know I can’t. And then, when I read the Colonel’s book on killing, it justifies it. I’m referring to the Colonel who did all the studies on it (referring to On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society by Lt. Col. Dave Grossman). During the Revolutionary War, how many guys pointed their guns dead aim at the enemy? Who can do that? When you get up to the Vietnam War, you’ve got only maybe ten to twenty percent of the guys pointing guns at the enemy. There are a lot of guys that will load them, but they’ll get them before the guys can pull the trigger. They had to come up with a concept to dehumanize the enemy, and that became “Gook,” and then, they raised it to eighty percent. It can be done, but I don’t like the idea of killing. I don’t like the idea of war. Who does? Nobody.

We’ve got a chance to make it as a race if we don’t do another world war. I think we’ve got a good chance and we seem to have learned a huge lesson there. I’m not going to live much longer, so I don’t know what’ll happen 30 or 40 years from now, but it’s really going to be interesting. We’re at the crux of a very important time. World communication is happening. You’re almost skipping the old process of you have to grow up and then maybe you can get to Europe sometime in your life. These kids are communicating directly across, back and forth, and that’s going to open up a lot of things. I think it’s exciting.

I know when I was raising my son, I said to Brawley when he was 12, when he moved in with me, “Do you want an open house or a closed house?” He said, “What’s the difference?” and I said, “Well, in an open house, we allow people to come in, but we have rules. There’s a bedtime rule during the school week and we allow a certain limited number in the open house. But, in an open house, you can have some friends living with you. In a closed house, there’s none of that. You go to school. You can have friends over for playtime, but they go home by 6.” Of course, he chose the open house, and right off the get-go I became the godparent for two kids whose dad had a new wife and wanted to go back to New York.

This film exposes such a vital part of American history that a lot of people don’t know about. When you first got the script, what was it that spoke to you about the film and about your character in particular?

Nolte: It was the yearning to tell the story. I’ve got the bug. I’ve got a distortion in me. I’ve got a love that Katherine Hepburn would say, “There should be a law against you having a relationship, because you love your work, and it’s not going to be fair to anybody.” I’ve got that bug. It’s killing me not being able to talk coherently about the generation of the Sixties that had such a phenomenal impression on this country to change and to accept and to say, “We don’t have to walk out with honor,” to say, “We’ve got to stop. Let’s stop.”

By God, the women throwing away that damn girdle was inspiration. I mean, you replaced it with hair from your ankles to the top of your head. It wasn’t about sex at all. It was about a girdle, that you wouldn’t accept your parents forcing you to wear something that really wasn’t healthy for you. And then, there was the men having to wear the same clothes in school. I don’t know if we could wear blue jeans, but we could wear different color khakis. It could be gray or tan. The only way I got away with wearing something different was I wore one red sock and one blue sock. And the way I got away with that was because I didn’t have a lot of money, and I lost the other pairs, so I only had one red and one blue. I didn’t dare show up with matching socks or they would have had me in detention for sure.

There are a lot of older iconic actors in this movie including you, Redford and Julie Christie, and then there’s Shia LaBeouf. Do you think the younger generation has it harder or easier these days?

Nolte: I don’t think it’s a question of harder or easier. I think it’s a question of, is this generation using the utilities and tools that it has? And [the answer to] that is a rip roaring “Yes.” They are using everything at their disposal, and it’s fascinating to them. It’s too bad we didn’t have the internet in the Sixties. It probably wouldn’t have happened, but there was a while there where our parents said, “These internet games are dumbing our children down.” Harvard did this experiment where they took a mouse and put him in a cage and gave him everything he wanted. At first, they studied dendrite growth in the brain. They did x-rays to see the dendrite growth. Then, they put another mouse in a cage and gave it everything it wanted, but it had to run on a circular wheel. Every time it moved, it would go round. And then, they put a mouse in the third cage, and they would take that mouse out twice a week and put him through a stress test – and not a little maze. I mean, it threatened his life. He had to cross a string (wire) 20 feet above a pool of water. It wouldn’t have killed him, but he would have thought he might be dying with that fall. At the end of this experiment, they killed the mice, and then they sliced the brain up to see the dendrite growth. The mouse that had everything didn’t grow a dendrite. His brain didn’t improve at all. The mouse that had to run, with just the physical activity alone, grew dendrites, but they didn’t hook up. The stress mouse hooked up and he grew tremendous amounts. So, there’s something about life and its hardness. It’s hard and it should be in meeting that and surviving. Like this whole idea of the guy who is the survivor, they always show a picture of a guy who is really strong, but that’s not the survivor. The survivor is the guy that socializes and can communicate with everybody. That’s who the survivor is. We’re social animals. We’ve got to get along together. It’s in our nature. We’re hardwired that way.

We had the Weather Underground in the Sixties and early Seventies, then a couple of years ago we had the Occupy Movement. Did you watch that? Were you encouraged by it?

Nolte: I don’t know what it is. Unfortunately, I just live in a little isolated world of a garden with vegetables and films. I do hang out with the Hare Krishnas, and the reason I hang out with Hare Krishnas is because that movement was started in the Sixties and [Swami] Prabhupada founded it in New York in the early to mid-Sixties. But it’s not because of the religious doctrine. It’s because they chant, and I do like to chant and dance, and they do that. So I’ll hold some Kirtans at the house, or I’ll go down to the Venice temple and do that. It’s hard, the Christian religion. When they were reconstructing the house in Ames, they came to a wall that was fibreboard, and on that wall was my sister’s writing and my writing when we were maybe four. I had written the Lord’s Prayer, “Our Father who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name…” and then I’d trail off. That’s all I wrote. My sister wrote something different. It was very strange to see what you had written when you were young and what was in your mind. I know that I had trouble with church because it went from church, then to Sunday school, and all of this. I finally put my foot down and said, “No, I’m not going.” And so, we went to church but we didn’t go to Sunday school. And then, the next week, we didn’t go to church or Sunday school. And then, my parents never did go to church. I figured out that they just did it because you were supposed to go to church. That doesn’t mean that I didn’t get something out of that church. I’ve prayed and been relieved. I only say that highly personally, but if it’s bad enough, I’ll say a prayer.

From the McCarthy Trials to the Sixties movement to gay marriage today, our country has a history where this different type of thinking generates a huge push back from our government. Do you think in this film that this is a specific witch hunt that Robert Redford and Susan Sarandon’s characters are going through or is it just a moral right or wrong tale?

Nolte: Nobody likes to change. And there’s only one thing consistently true. There will be change, and that’s just the dilemma of it. There will always be resistance to change, and there always will be change. And the quicker you get to that, the easier it is. It’s not such a difficult thing. If you entrench yourself and go, “By God, I will not change. I will not have this.” Then, you’re a dead man. We’re great at adaptability. It’s our strongest suit. It’s not 18-inch arms. That doesn’t do anything for us.

Can you talk about your thoughts at the time in the Sixties regarding the Weather Underground and whether your feelings about them came to change?

Nolte: I didn’t really even know of them. They were such a fringe group. I had heard about them, but violence was something I was trying to avoid. I’ll tell you one case, because I was brought up this way, and I talked and I talked, but I couldn’t do the walk. At Greeley, Colorado, the Little Theatre of the Rockies is a very famous summer stock place. Professor “Lang” (Helen Langworthy) was the director of it. I was a guest artist, so that meant they paid me enough to buy the little cans of spaghetti and stuff like that. It was great. It really was. I had gotten there two weeks early before rehearsals would start. One of the acting members had studied for the priesthood, and there was a Civil Rights march going on down in Mississippi, and I had talked about this the year before. And he said, “You know, Nick, we’ve got two weeks. We can be down in Mississippi and back. Let’s go to the march.” And I said, “No, no. I’ve got to learn my lines.” It took guts to go on a march. It took really stand-up people. That, I do know about. But, the Weathermen, no, I don’t know about them.

I did get upset when the LAPD shot up the SLA (Symbionese Liberation Army) in that house. It wasn’t that they shot them. It was the way they did it. They had them surrounded. They didn’t need to shoot. It would have been so civilizing to have that kind of action happen rather than the house jumping with bullets. It was shocking. A lot has happened in our time. We’ve seen a lot. 9/11. I would say that every generation will be challenged morally once in their life about their government and their way, and they’ll have to say where they stand. It happened in the McCarthy hearings, which Marty (Scorsese) took great offense from, but I didn’t applaud that, and for quite some time, he wouldn’t speak to me. (Nolte is referring to their rift which stems from the 1999 Oscars when Nolte refused to applaud when Scorsese presented Elia Kazan with a lifetime achievement award, even though Kazan had named names for the House Committee on Un-American Activities.) Then, he put it aside and we’re friends again. I couldn’t stand not being a friend of Marty Scorsese because of the artist he is.

You began your career at the Pasadena Playhouse, then you started doing some Quinn Martin shows before your breakthrough role in Rich Man, Poor Man. What were your acting dreams at that time? Did you have the acting life that you imagined?

Nolte: What I was aware of was that you have to act. You need to act. So, go act. I did regional theater for 14 years. I had a whole circuit. I’d work in Phoenix. We developed quite a few repertory companies out of there: the Southwest Ensemble Theater, Actors Inner Circle. Then, for a job so that you had money, I would go up to the Old Log Theater. Bob Aden, this older character actor who was a marvelous actor, took me up there, and Don Stolz hired me. Don Stolz was always telling me that if you want to really be a man, you’ve got to get your college degree. He had the problem of keeping these actors up there in Minnesota, so he would try to maneuver you into staying. He would go to Broadway and find some lead Broadway actor that was on the skids and offer him a job for life, and that was John Barnum. So I had that circuit, and I would run that for four or five months, and then I’d scoot back to Phoenix. I had the Inner Players in San Francisco. I went to New York on a Prestone antifreeze commercial. I was married at this time. I was married at 22 to a 32-year-old woman (Sheila Page) who was the most beautiful woman in Phoenix. She was. There’s no question about it. We were doing Miracle Worker. She was playing Annie Sullivan, and I was playing the younger brother. The whole company would go out to the restaurant to eat. There would be a line of businessmen from Phoenix just lined up waiting to say hello to Sheila and she couldn’t take it. One day she reached under the table and grabbed my hand and said, “I’m taking you home with me.” And I said, “Okay.” And I never left. She went through some harrowing situations.

One of them was … I think I can tell this story. I had this photography professor that I was working with, Allen Dutton, who was a friend of Minor White’s. We were shooting what they called “equivalency,” and that’s your relationship to an object and where you intersect with that object and try to find that as your focal point. We have relationships with every object. If you really look hard, it’ll just spring out at you, and that’s what you want to shoot. But, even beyond that, you want to shoot, if you can, where you leave off and the object begins. That’s your focal point. It was amazing, fun stuff to do. Allen got a letter and some little chips from Larry, Professor Halpert, and he didn’t have anybody to do this with, so he showed me the letter. We’d go out in the desert and take LSD. I did this for about 8 trips with Professor Dutton who was 40 years older than me, which was fine. It was no big deal. On the eighth trip, we were coming back, and I guess Allen had gotten into a little bit of a struggle, some kind of ego struggle or something, because he turned to me and he said, “You know you wouldn’t make it without me.” And, in one sense, that’s absolutely true. And, in another sense, it’s absolutely bullshit because we will all make it. We’re alright. His teacher came out for a second, and he saw it and I saw it, and that was the last trip I took with Allen. I think he went on to take another couple hundred trips, and his photography changed tremendously and brilliantly in a way.

That’s another thing. A lot of the vision, the way we see things, were changed from these psychedelic trips. It’s not that that was a new thing. That had been around for thousands of years with mushrooms and things like that, and it’s always been assimilated into the culture, either religiously or in storytelling or in some way. What gets me is the attack of a plant when it obviously has a symbiotic relationship with human beings. All these plants are part of us. If you started out trying to eat broccoli in the wild, you couldn’t have eaten it. But somewhere along the line that plant said, “Hey, listen. I’ll make a deal with you. You take care of me and I’ll be your food.” There is a relationship going on there. I mean, we don’t have the senses to know it, but they’re beginning to find it in labs, and they know there are emotions.

Did your third nomination for an Oscar for Warrior in 2011 change anything?

Nolte: I never liked the Oscars. They didn’t do too much for me at all. I felt like a big, vulnerable hunk of baloney being used to sell some products. They asked me once to be a presenter, and I said, “Yeah, I’d love to be. You give me one quarter of one half percent of profits.” “No, Mr. Nolte, everybody does this for free.” I said, “Yes, I know, and you’re the biggest show on TV, bigger than the Super Bowl. You can share one quarter of one half percent.” And that was it.