When I walked out of John Wick back in 2014, I thought to myself, "I need to know more about this world." John Wick as a character (Keanu Reeves, of course) is a primal character, symbolic of a streamlined, professional form of terror and mayhem, so stripped of any unique, human qualities that he's known literally as the Boogeyman. As such, I found myself gravitating to the film's impeccable world-building for sources of inspiring imagination. Lance Reddick runs a neutral assassin hotel? Coins are currency for the most unspeakable acts? There's a cabal of ruthless bounty hunters who are activated at a moment's notice, all with badass skills and scowls? I had so much fun guessing what all these specifics meant for the world of Wick, and had even more fun seeing them blown out in Chapters 2 and 3.

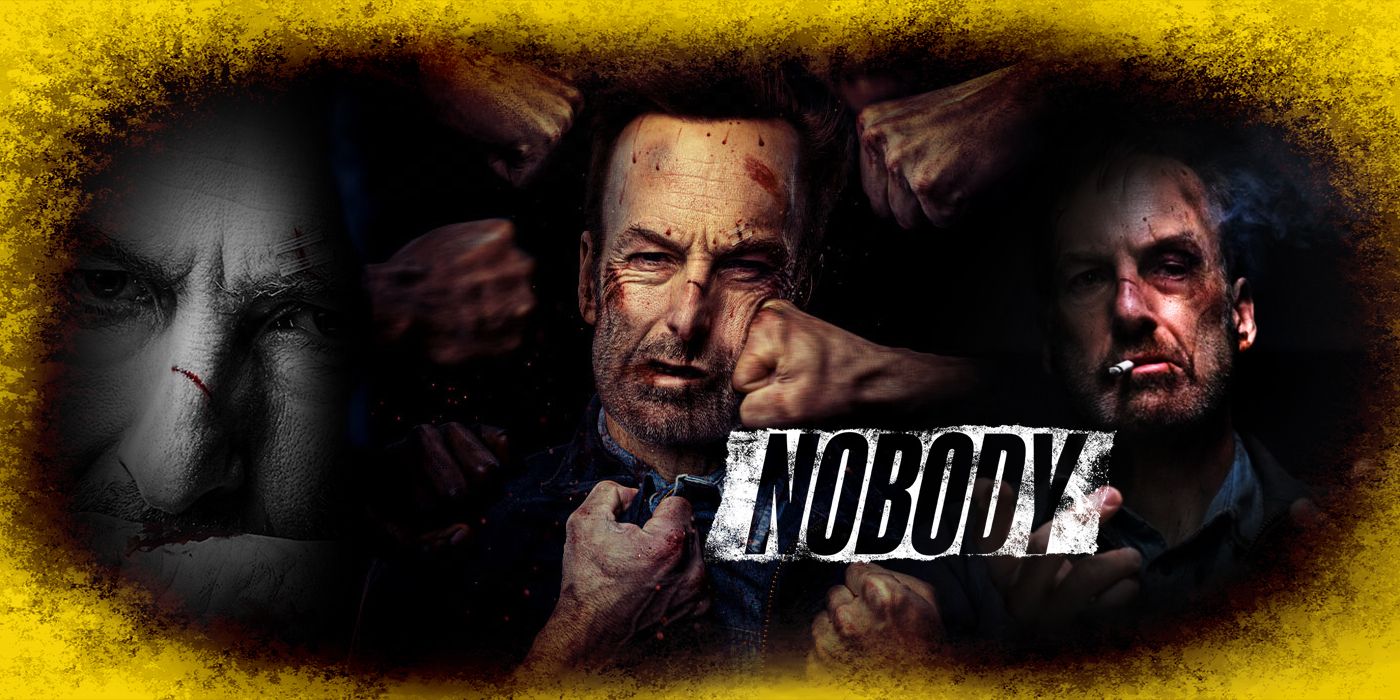

2021's Nobody is written by Derek Kolstad, who also wrote John Wick. The films are both brutal action-thrillers with shady organizations and capable warriors; given these genre similarities, the same screenwriting source, and the cultural love of all things Wick, folks were more than wanting to compare these two. Kolstad himself commented, quite effusively, on these comparisons to us: "I fuckin' love that comparison, man... I'm not here to reinvent the wheel, I'm here to make a really good wheel and you're like, 'I wanna fuckin' ride on that wheel.'"

Both films work as wheels, driving furiously from set piece to set piece. But when I recently revisited Nobody on brutally gorgeous 4K blu-ray, I walked away thinking, "I need to know more about this person." The film hints at darker shadows of underground organizations and what Bob Odenkirk's Hutch Mansell means in the context of a wider mythology, no doubt. Primarily, though, it's a character study, purposefully limited in scope, zeroing in on the journey of one human being, rather than the shiny coins around him. Nobody's the wheel of a Smart Car versus Wick's wheel of a monster truck.

Hutch's status as our action movie hero, our guy who's gonna beat the bad guys up, our reason for engaging with this genre, inherently has a personal, unique arc baked in. Our opening moments, chopped with ruthless efficiency by director Ilya Naishuller and editors Evan Schiff and William Yeh, reveal a person completely broken down by the banal demoralization of life. He's bored, boring, unable to do the most basic things like offer a worthy enough financial deal or take out the trash or physically comfort his wife (Connie Nielsen). Thus, when the first hints of action kick in, there are an immediate sense of personal stakes that yield a character-driven sense of audience suspense. We don't know if we're about to watch a guy kick the shit out of people or get the shit kicked out of. The best fight sequences in Nobody feature an equitable slide between both sides of the continuum, constantly surprising us, constantly aligning us to the emotional journey of the character beyond the craft of his action (compared to John Wick's cartoonishy invincible but inherently removed "somersault gun-fu"; not an insult, just fundamentally different from Nobody's intentions).

In fact, our first whiff of action does not end in action. When goons invade Hutch's home and threaten his family, Hutch stops himself from fighting back, instead whimpering for a détente. The movie's response to this choice is comical in its righteous demanding for Hutch to become an action hero already. The arriving police officer (Gabriel Daniels) muses aloud "if this was my family..." His obnoxiously mid-life-crisis-laden next-door neighbor (Paul Essiembre) wishes the goons invaded him, because he "could've used the exercise." His brother-in-law/co-worker (Billy MacLellan) calls the interaction "child's play" right before pointing a gun at Hutch's head and insisting he "keep my sister safe, bro." There's not much world-building that needs to be done. The world is ready for Hutch to engage in it, to fuck it all up and be our Boogeyman brawler. But Hutch doesn't want to engage in this brutal, bloodthirsty world, let alone expand it out even further. The film predicates on his interior conflict between backsliding into a Boogeyman or freezing as an everyman, a unique tension that forces us to zoom in on him with a tight lens rather than check out the world with a wide one.

And when Hutch does answer his "hero's call" and begin his bloody rampage of revenge, his engagement with a "criminal underworld" is less an intentional, boot-shaking choice, and more an idiosyncratic, boot-scraping stumble. Instead of reconnecting with his fellow anonymous assassins in seductively encrypted messages, he talks to his family, father Christopher Lloyd and brother RZA (even his allies in arms are kept at a personal, emotionally-bonded, character-driven range). Instead of trading coins and quips with a dashing concierge, he fakes an old FBI badge and bumbles his way through intel by sweat and dumb luck. And most tellingly, instead of electing to take down the Russian crime boss Aleksey Serebryakov, he is accidentally thrust into his atmosphere by virtue of an accidental bus fight (whoops, one of the goons was his son). Not even the introduction of a crime boss does much to "blow out the world," as it's established Serebryakov's character is an isolated, eccentric duck; a fittingly personal, emotionally, and performatively compelling foil to Hutch.

Two things happen when Hutch slows down in an attempt to explain, explicitly, his backstory and mythology; to "build out his world." The first time he does so, the person (Araya Mengesha) he's telling his compelling tale of agencies and "auditors" and high-stakes global espionage to just kinda dies in the middle. It is a laugh-out-loud moment, a pulling of the rug that works as an ironic reversal of what this world seems to want from Hutch — first it demands him to be a shady action hero, now it can't be bothered to listen to his badass speech? — and as a reminder of what's the most important goal for Hutch's personal journey. As he explains in his second world-explaining story (which he actually gets to complete), Hutch doesn't want to annihilate the criminal enterprises that bind him until his sense of vengeance is satiated — at least, not too much. He recognizes its an inherent flaw in him, this quest for violence and vengeance, this pressure to exist in an expanding world of intrigue and mayhem. Instead, he wants to live life like the random mark he let go so many years ago. Bored. Boring. Happy.

The ending of the film gives us our bloodshed, and gives Hutch a sense of closure. Despite the winking button that hints at a sequel, you can feel the book close on his world. However, the author's voice, no matter how anonymous it insists it wanted to be, remains powerful.