It isn’t just Andrew Sarris and the French critics behind auteur theory whose sympathies lie with film directors. They seem to achieve celebrity more easily than anyone else behind the camera, and they are the figure most responsible for making the movie. It’s easy to think that directors must be the chief creative force behind a picture – or that they should be. That’s certainly the view I tend towards, and not just because of years in film school or long-term hopes and dreams. The plain fact is, however, that filmmaking is a collaborative process. Not even a Stanley Kubrick, a Martin Scorsese, or an Akira Kurosawa is responsible for every bit of good that finds its way into their movies. And there are times, for good as well as for ill, that a director functions more as an on-set traffic cop executing a vision primarily channeled through someone else. If that figure isn’t the director (and if corporate meddling from on high is minimal), it’s often the producer.

There are celebrity producers, figures whose visual, narrative, and thematic tastes are so prevalent that they become as recognizable as any director’s fingerprints. Just ask anyone who worked for Walt Disney whom the final arbiter was on any major creative choice for his movies. In the days of the Hollywood studio system, producers like Hal B. Wallis and William Alland may not have become household names the way Walt did, but they still often set the tone for their productions more than their directors. But are times when a “producer’s film” is, even among hardcore film aficionados, not recognized as such.

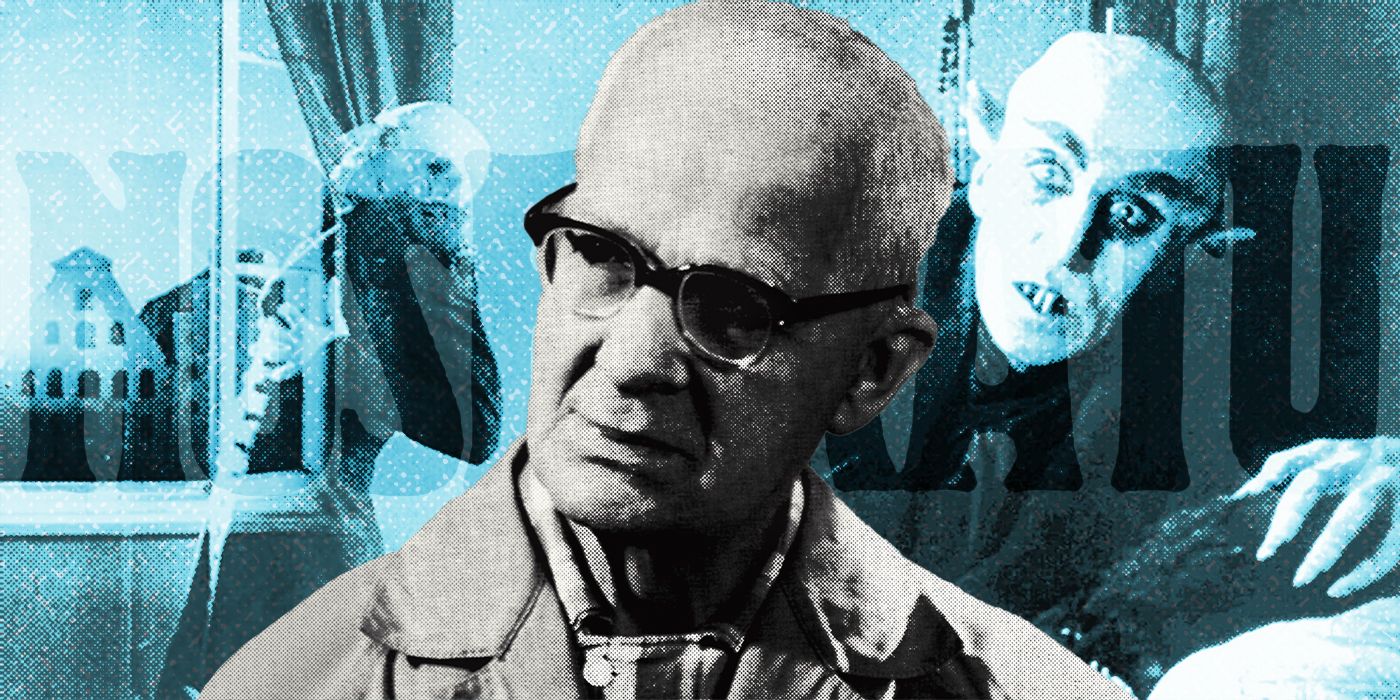

Take Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror, now enjoying 100 years of its undead existence. The rat-like visage of Max Schreck as Count Orlock has been well-absorbed into our culture, as has the film’s reputation as one of the most frightening movies ever made. Besides Schreck, the greatest praise for Nosferatu’s many virtues is given to its director, F.W. Murnau. And why not? Murnau is among the most renowned filmmakers of German silent cinema. In collaboration with crew members, Murnau pioneered innovations in camera and editing through films like The Last Laugh. Sunrise, his Hollywood debut, is still often counted among the greatest movies ever made. While few details about the production of Nosferatu (or most silent films) survive, biographer Lotte Eisner’s efforts uncovered a picture of a meticulously prepared director, working efficiently but with artistic integrity despite a meager budget. And Murnau has generally been credited for rewriting the ending to introduce the notion that vampires can be destroyed by sunlight, a concept new to vampire lore at the time.

But Nosferatu was not Murnau’s baby. The Expressionist aesthetic, the monstrous design of Count Orlock, and the very idea of doing a vampire picture all came from producer Albin Grau.

To call Grau an unsung hero of cinema may be an overreach. Nosferatu was his only credit as a producer, and his resume for any kind of film production work is scant. Primarily an artist and architect, his poor business decisions put a quick end to his cinematic ambitions and severely jeopardized the fate of the one movie he did get made. But as the man responsible for much of what makes Nosferatu such a milestone, Grau is due his credit.

While promoting Nosferatu, Grau claimed that he was inspired to produce a vampire movie by an encounter during World War I: an old farmer told Grau that his father had been a vampire. Whether there was such a farmer, Grau’s interest in supernatural and occult subjects ran deep. Besides his professional work, he was also a practicing occultist, for a time a member of the magical order Fraternitas Saturni. Nosferatu was intended as but one of several pictures on occult and supernatural subjects produced through Grau’s company Prana-Film. He hired a fellow enthusiast for the subject, Henrik Galeen, to pen an Expressionistic screen adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, and while the extent to which any occult practices or messages made it into the finished film is an open question (one assessment found none at all), Grau did incorporate alchemical and hermetic symbols into a key prop: Count Orlock’s correspondence with his servant Knock.

It was well within Grau’s purview to set the look of a prop like that, and not only because he was producing the film. Grau also served as the production designer. Traditionally, this would mean working with a team of art directors, in partnership with a costume designer. But Grau seems to have personally designed everything to do with Nosferatu. A limited budget necessitated extensive location shooting (unusual for the period, and detrimental at times to the story that established vampires as sun-allergic), but what sets could be afforded, Grau conceived. The grotesque make-up of Count Orlock, Grau designed. And the film as a whole, Grau styled, through many detailed pieces of concept art that often capture the intended nightmarish spirit of Nosferatu more than the finished film. These sketches were paired with a script full of instructions on camera placement and lighting. Murnau deserves credit for overseeing filming (apparently using a metronome to dictate the performances of his cast), but aesthetically and thematically, Nosferatu belonged to Grau. The ending is the only major deviation Murnau made from the tightly designed blueprint given to him.

Grau’s control over Nosferatu’s visuals extended beyond filming. He personally designed and executed many of the film’s promotional materials. The ad campaign ended up costing more than the movie itself, capped off with an elaborate costume ball in the Berlin Zoological Gardens following the premiere. Some surviving posters, like the concept art, are striking depictions of horror and decay, a far cry from today’s stock images of actor’s faces. But blowing so much cash on the ad campaign did nothing to help the finances of Prana-Film, one of many tiny production companies in Weimar Germany, and it wasn’t Grau’s worst business decision.

It's become part of Nosferatu’s legend that the character names and the setting of the story were changed in an effort to mask the film’s debt to Bram Stoker, but film historian David Karat has argued that this is a legend without any sources. The original credits for the film described it as “freely adapted” from Dracula, hardly the sort of claim someone would make if they were trying to get away with plagiarism. More likely, the name and place changes were made to appeal to the German audience. But while the debt to Stoker may have been acknowledged, Grau either did not know or did not bother to obtain legal permission to do any adaptation of Dracula, free or otherwise. Enter the widow Florence Stoker, dependent on royalties from Dracula as her income. Through the British Society of Authors, she launched a suit against Prana-Film to obtain financial reparation. Beset with this legal battle and its unstable finances, Prana-Film declared bankruptcy shortly after Nosferatu’s release. By the time the case was resolved in 1925, Florence obtained a ruling that the negative and all prints of Nosferatu be handed over to her and destroyed, but by then, the film was too widely distributed to be wiped out entirely.

How much Grau was personally burdened by this suit or by the loss of his studio is unrecorded. He eventually left Fraternitas Saturni over internal disputes, and Germany over the rise of Nazism. He returned after World War II to a career in commercial art, his contributions to one of the foundational works of horror cinema overlooked in favor of Murnau’s. When the making of Nosferatu was fictionalized as Shadow of the Vampire, Grau (Udo Kier) was turned into a hapless producer in name only, forever at the mercy of the perfectionistic “Herr Doktor” Murnau (John Malkovich) and the real vampire Max Schreck (Willem Dafoe). Other problems aside, that storyline seems a missed opportunity to me, given the real facts of the production – wouldn’t a frustrated Murnau’s struggles to make the film his occultist-producer wanted, a producer whose magical practices summon the undead to take part in filming, have been more fun? But a century after its premiere, the imagery of Nosferatu, designed by Grau, has a fame outshining any of its participants or descendants. If there is anything to Grau’s occult practices, perhaps his shade can take some comfort in that.