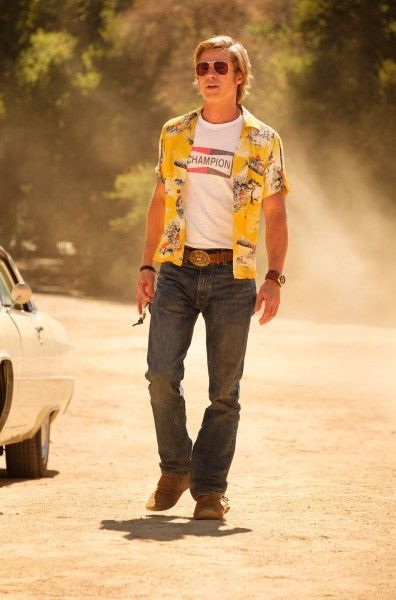

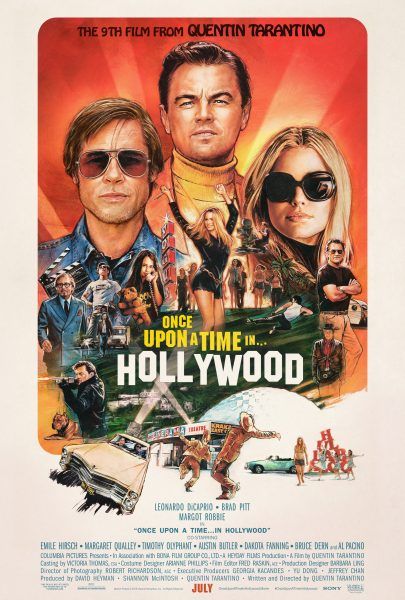

Robert Richardson is not only one of the best cinematographers working today, he’s also one of the closest collaborators of one of the best writer-directors in history. Richardson has worked with Quentin Tarantino on five films now, dating back to Kill Bill, but their latest collaboration is one of their most satisfying yet. Once Upon a Time in Hollywood takes place over the course of three days in 1969 and follows the lives of a fading TV actor named Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio), his laid-back stunt double Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt), and shining star Sharon Tate (Margot Robbie)—Rick’s next-door neighbor.

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood brings 1969 Los Angeles to life in a way that feels vibrant and vivacious, but it’s also a deeply intimate story of these three characters. Richardson’s cinematography at once evokes the epic promise of Hollywood, but also the personal triumphs—and failures—of those trying to make it. Along the way, Richardson and Tarantino delightfully capture life on a Western TV series set, evoke the spookiness of the Manson Family-filled Spahn Ranch, and go dark for a truly shocking (and ultimately touching) grand finale. The striking nature of images onscreen is a testament to both Richardson’s and Tarantino’s talents, but despite the varying locations and landscapes, all feel like pieces of a whole.

With Once Upon a Time in Hollywood now playing in theaters everywhere and continuing to rack up an impressive box office tally on the heels of positive reviews, I recently got the chance to speak with Richardson at length about his work on the film. During our wide-ranging conversation he discussed his close working relationship with Tarantino, how they nearly shot all the Lancer scenes in 70mm, the way in which they approached the film’s driving scenes and Spahn Ranch, working with DiCaprio and Pitt, shooting the scene where Sharon goes to the movies, and much more. Richardson also spoke about Tarantino’s retirement as we commiserated over the filmmaker’s potential exit, and he talked a bit about what drew him to sign on to shoot Venom 2 with director Andy Serkis.

It’s a wide-ranging discussion that’s made all the more insightful by Richardson’s candor and genuine passion for film and filmmaking. Check out the full interview below.

You’ve worked with Quentin a number of times now, but I was kind of curious what your initial conversations were about what does the film look like?

BOB RICHARDSON: Well, early on we also talked about Rolling Thunder, and the look of Rolling Thunder, which Jordan Cronenweth shot, and we utilized it as, "I would like my blacks to be this black," with one sequence. I don't know if you remember the film, but William Devane, there's a sequence inside the kitchen and it's rather gruesome, but the blacks there were raised as an issue in terms of “I'd like to have this darkness and yet make it feel natural.” So that was one of the first things we talked about specifically, in terms of the final sequences of Once Upon a Time. As to the rest of the film, initially he was undecided whether we would shoot it for 70mm, or part of the sequences in 70, and then the rest in 35, and it all ended up going 35mm with what he described as a retro look but yet feeling contemporary.

Why did you decide not to go 70mm?

RICHARDSON: Well, I think that we decided—first of all he needed zooms for the sequences. He was thinking, for him the primary sequence would have been what is Lancer. So that we would have shot in 70, and then as he went through and developed a shot list—because that was quite early in the process in which we initially started talking about the movie—he felt, "Okay, I need a zoom so that takes us out of 70 no matter what,” so we dropped it.

That makes sense. You guys have worked together a number of times. I was kind of curious how the experience of making this film was either different or similar to your experience on other Quentin projects?

RICHARDSON: I mean, in a similar sense that you're working with the same director, a lot of the same team around, his methodology hasn't altered through the years in which I've worked with him from Kill Bill till now. He doesn't leave the set. All of those aspects of being very close to the camera, never leaving, and keeping a happy set existed in this film. I think the difference is that our relationship has shifted from something that was more at a distance as we learned each other in Kill Bill, and by now we both know and trust each other implicitly. I think we have grown together as a creative family, getting closer and closer. So this is the closest experience I'd had with Quentin from all the other films. I mean, it just for some reason has shifted in the last two films, closer and closer, Hateful Eight and this.

I think part of that is the loss of Sally Menke, who was his primary collaborator and extraordinarily important to him, and that was a tragic death. Somehow I think I partially have filled a bit of the void of Sally. You can't replace Sally, it's a very long relationship, but I think he sees my relationship with him as something which is akin to that, although not at the same level.

Well it's a fruitful relationship to be sure. I've really enjoyed watching that relationship evolve. If you look at the films you can tell it's the same filmmaker, and it's obviously shot by you, but there is a bit of a different style to them all that I enjoy.

RICHARDSON: Yeah, I think that Quentin has... I don't know what it is, but he just feels emboldened. There's really nothing he can ask me to do that I won't make happen one way or another. He's become extraordinarily confident in his work. I think it's clear as you watch each film, whether it's Reservoir all the way to this point, you can see his directorial skills. I mean Hateful Eight is a masterpiece in terms of what he did with actors in a small space, just remarkable work and under-appreciated, I believe. And this film is a fly. I mean, it's just such a beautiful film because it feels as if you are literally surfing Los Angeles.

Well, and to that point, one of my favorite sequences or number of sequences in the film are the driving scenes. You just feel like you're flying down these streets. I was wondering if you could kind of talk to the approach to those scenes. Because obviously Quentin served as DP on Death Proof, but there's something about these driving scenes that feels different and energetic and kind of really puts you in it.

RICHARDSON: Well, I think they're not shot in a way which you would have done on Death Proof or something like that, but what you do have is the underlying score of the film. The music playing from KHJ just gives you this momentum in all those sequences. He has so brilliantly aligned the image with the music that... I mean it's one of the best soundtracks I've heard in the longest time because I'm constantly put into the exact time period of '69, number one, but I just feel as if I'm grounded and he gives me the energy in which to experience that scene from the music, which is coming right off the radio. So of course all those sequences are in my mind, about why they have that sense of freedom that you're talking about.

And of course we were very free. We just shot the best we could and gave it as much energy as possible. When Brad was driving, Brad drove fast; he's not driving slow. He's got this sensibility. He's very competent at the wheel, and we had a very competent driver with the car. So we would push it a little further in terms of letting the camera find its space. Quentin was specific like, "Come about, come around, behind," etc. etc. But I think that's one of the reasons it has that level of freedom, is primarily due to the music.

I also just think the way it's shot. I mean, I agree with you, the music is a huge part of why it works, but I mean specifically the sequence where we follow Brad's character home on that first night. I just love the way that feels.

RICHARDSON: I do too. There's a sense of freedom in it. It's just like you're just rocketing down the streets. It's just that sense of freedom he wanted and we pushed very hard to achieve it. That's a lot of work when you think about, those backgrounds aren't CG backgrounds, but yet he's not focusing on those backgrounds either.

I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about working with Brad and Leo. I mean, when you cast actors as famous as they are in a movie about Hollywood movie stars, obviously there's something the audience is going to bring to it. I think that works in the film's favor, but it's just so incredible to see these shots where you just have two of the biggest movie stars on the planet together in the same shot.

RICHARDSON: Well, I can definitely talk to that. I also think there's a third component in that, which is not only do we have Leo and Brad and Margot, but we also have Quentin. Because his public following is so strong in terms of his films, everyone sort of knows where Quentin’s going, or they think they know where Quentin's going. So you have that element that's on top of Leo and Brad, which was an absolute joy and will be impossible to duplicate that again. Will not happen, especially with a script this full of life. I mean we've talked about it before, but it is sort of a very similar world to The Sting or Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. When you put Paul Newman and Robert Redford together, I think Leo and Brad are very much this generation's very finest stars. It was remarkable to have that. I feel so lucky, so fortunate that I'd be able to shoot them together.

Their friendship just kind of drips off the screen, too. That's not something that's super easy to accomplish.

RICHARDSON: No. When you have a relationship in a movie between a man and a woman or a man and a man, whatever it is, even if it isn't sexual, if they don't have the chemical element, then it doesn't work. You can feel when love doesn't work on a screen just as you can feel with a friendship. This friendship works extraordinarily well on a screen because they clearly were at ease with each other and had been doing this in a similar way for so many years. Both of them started in Hollywood at a very young age, they moved up through it, they've had huge levels of experience. To me, whenever you saw them sitting together, it felt like two guys just hanging out at a house. They just were totally comfortable and then they perform and it's just remarkable. It's like, why? Why is this working so fucking well? I don't actually have an answer to it, but it was magical.

I love the scene where they watch FBI together.

RICHARDSON: Yeah, they were great together.

There’s a big Western element to this. Obviously Quentin with Hateful Eight and Django really got into a groove with Westerns and it's kind of like he almost makes his third Western inside of this movie, specifically with Lancer. But I was wondering if you could talk about shooting those sequences, shooting Bounty Law and stuff, and then the decision to present Lancer as if it’s part of the film.

RICHARDSON: Well, I can talk about the fact that when we tried to shoot the Bounty Law material, we went back to Steve McQueen and looked at his films. Basically we tried to emulate them, to a degree, although I think it's clearer or sharper, which is where the sort of modern element on the retro goes. So we did shoot in black and white. We lit it in a similar way, I use hard lights, things I wouldn't ordinarily do in a sequence, to try to get underneath the hats and such. That differed substantially from the way we shot Lancer. I did see Lancer of course, but I also watched Alias Smith and Jones, which was rather influential in terms of the attitude. If you've seen that, I think you will see a comparison that will make sense to you in terms of the attitude within Lancer.

Then you're absolutely right, the only introduction you really have to Lancer, initially, is the walk to the set from the trailer and a bit of it in the background when they arrive initially, but once you start the scene you're in the movie. And I do believe this was Quentin’s desire, just as you have noted, to be his next Western. And we were willing to make more of it and that's why we talked about it initially possibly being 70mm, but decided in the long run it wouldn't work. But I did like the way that it's a movie within a movie, because you are within the characters and then suddenly it's, "Line, line, line." That is such a brilliant break. Anyway, I think that's where Quentin's genius is.

Yeah, it's fantastic. What I also really like about it, though, is that you have Rick on this Western TV show set and you contrast that with Cliff at Spahn Ranch, where he's literally in danger. I was wondering if you could kind of talk about the shooting of the Spahn Ranch scenes. It gets really spooky and kind of terrifying.

RICHARDSON: Well, that was the entire goal, to sort of initially step into this as a large, empty vacant space for him. It's not until you cut to the interior where all the family is lying down watching television that you get a sense that they're watching, they want to know who he is, and then it becomes more about, "All right, he's here. He seems to be okay." And then he, meaning Brad, starts to push the buttons up, "Is that where George lives?" We move that direction with them, and as you moved, the thought pattern between Quentin and I—well, really Quentin—was that as you move toward it you begin to feel that the family's starting to circle around, worried. And they push that attitude further and further till you end up with mama bear right there with Dakota [Fanning] and it's like, "I'm going in that door," and they go in that door.

Then we kind of shifted the lighting into something which we didn't use anywhere else, which is a bit more horror film. One spot for him to hit the light just before he goes down the hallway, then darkness in the hallway. Silhouette at the end. We played more in the horror genre than we did anywhere else in the movie. As you know, the whole scene with Bruce is that you don't know when he opens that door what we're going to find. And then exiting, of course, it's ratcheted at a higher level than it was before. And that was his goal, and I think he really succeeded extremely well. Particularly in a sequence where the guy that has stuck the knife into the tire upon exit, and that movement between slow motion and normal speed, gives it even more power.

I love the scene where Brad's just strolling back to his car and he's just being yelled at by all these hippies.

RICHARDSON: And also Margaret [Qualley].

Oh she’s so good.

RICHARDSON: When she’s up on the car, like Wicked Witch of the West, you know? Hand pointed out. I really loved that little piece. I mean she is amazing in the movie. And Austin Butler too.

Everyone’s so good in this movie. One sequence that everyone seems to be talking about, and is one of the best parts of the film, is where Sharon goes and watches The Wrecking Crew, which is this really wonderful, touching sequence. I was wondering if you could kind of talk about the construction of that scene, because I saw Quentin said recently there was maybe some pushback on including it.

RICHARDSON: I can't even imagine this movie without that sequence. Just to see her watch her own work. I think the insecurity of actors, period, is something that goes on display there. I mean, an actor has to be an actor and you always ponder whether or not your performance is actually achieving what you attempted to do, and to watch it in front of somebody to give it validation is a rather remarkable sequence to watch. It's just to have her sit there and smile and give that, put those glasses on, her feet up and enjoy it, enjoy their laughter when it should be laughter and their applause when it should be applause. I think that scene could not be removed. If we had lost that, I think we would have lost Sharon Tate's character to begin with.

It's pretty impeccable. But in terms of actually shooting that scene, I was wondering if you could talk about how you guys went about that. Was the footage from The Wrecking Crew actually projected on the screen you when you were walking in? Or was that kind of added in later?

RICHARDSON: Yes. Yeah, the only time that there was a digital projector utilized was the sequence for the drive-in theater, when he arrived. But all the others are done with film inside the house, and sort of a projection booth was built to allow us for the best projection possible if necessary when we had to do it. But yeah, it's all film. And same thing with when Al Pacino watches those movies, those are movies that are projected on a screen or captured on film.

Oh wow.

RICHARDSON: So it was no VFX involved.

So did Quentin have it pretty specifically in his mind how he wanted to shoot that? I mean, with her coming in the door and then she starts to kind of dance to the trailers.

RICHARDSON: Yes. We had an issue getting into the position of the seat, so we modified the entrance down with her, following her from behind low, as she sort of swayed her hips to the sound, and then we came up. Because we couldn't get the camera to come in accurately at a higher—if you were too high, it would not allow us to get low enough behind her at the moment she's viewing the film. So we ended up having to go with a low mode on a steady cam to achieve that, and as a result of that, as opposed to aiming up high, we aimed low on her hips which was I think really beautiful. You know, he accommodated that technical problem and that's where you see what you got. And of course all of that's sunk up through the screen.

That’s crazy.

RICHARDSON: Why is that crazy? Cause it's so old school?

It's just really cool. I mean, so many other filmmakers would just have cheated it or used a green screen.

RICHARDSON: No, yeah. Lots of people would just project a green screen and pick what they want later. Quentin specifically picked what he wanted to see exactly at the moment. Quentin is precise. It's not like, "Oh, I don't know what I want." He says, "This is what I want. You make sure I have what I want when I shoot it." He's not, "Oh we're going to wait until later and see what we can do." It's the same reason he shoots with one camera mostly. It's like, "This is the angle I want. I don't need another angle. I don't need two cameras. We're going with one, because I'm a director, I'm not a selector."

So what's that collaboration relationship like with you then? Is he dictating exactly, specifically what every single shot is? Are you guys kind of working together to figure out the shots?

RICHARDSON: No, I wouldn't use the word dictating. Quentin comes in with a shot list, and that shot list is what we shoot. If there's a problem with getting a shot, we talk about the problems that might exist with a shot, and that's it. We go forward. Same as Marty [Scorsese]. Marty puts down a list of shots and that's what you're doing. You're doing his shots. Same virtually with everybody I've ever worked with. Almost everybody has a full on shot list, and that's what you try to accomplish. Now sometimes you do end up working more with people to try to find a blend. But with Quentin it's a list, "These are my 16, my 18 shots for the day and I want these." And that's what you do.

So what was the most tricky for you to pull off then? Was there a particular sequence or a shot that was really tough?

RICHARDSON: Well, the most complicated shot, as you can probably well imagine, are the two shots at, number one, the one that ends the film and then the one that pulls back from the pool. You know where Leo's in the pool and it comes over the roof and comes into a medium shot of Sharon and Roman.

Which is incredible.

RICHARDSON: I mean that was a very hard shot to accomplish, took a very large crane, it required a zoom to be attached. It fell into place much easier than I anticipated it would, but we struggled for a long time in solving what would be the right piece of equipment to achieve that. That, and the other shot where they're behind them and you see them walk up and then you go up through the trees, and you can sort of pick them up the whole way through till they end up in an overhead of, as they all come up, then you end up with as you know, the ending, “Once Upon a Time…”

Yeah, which is beautiful.

RICHARDSON: So those were the most complicated.

Well, I was gonna ask about that first one because it's a really breathtaking shot, as is the final one. I'm not supposed to get into spoilers, but I was wondering if you could kind of talk about, for the third act, there's a big change in lighting, you're in the darkness. I was wondering if you could kind of talk about that approach and kind of working in those scenes that way.

RICHARDSON: Well, that's exactly where when we first started off this conversation, and we talked about a film, Rolling Thunder. That's what we were searching for, so it was lower key, it was dark or underexposed, not a lot of lights, and meant to be that way. And from the car to the house, etc., that's… We're not doing spoilers, I won't go in to the issues of specifics, but what you're looking at there is the reference was Rolling Thunder and the result was what you have seen inside the house in the sequence. I mean, in terms of negative and no real backlight to edges, we tried to work with really low light levels. We pushed the film stock, get more grain.

You see a lot of films that are period and they're set in the past and they try to find ways to tell audiences that you are in the past with the camera. This is a film that feels very, very much like it's leaning on production value as opposed to trying to use camera tricks or softening the image or something like that. I was wondering if you could kind of talk about just bringing 1969 Los Angeles to life visually in a way that made you feel like you were there with the characters.

RICHARDSON: Well, I think you're right. I mean, there's always the option of trying to make this film stock appear to have a time element to it, whether it's grain or this or that, and we have that. But what you're leading towards is, the reason it's as successful as it is, is because costume, production design, hair and makeup give you the reality of the space. Production design gives you the physical and the broadest element, which tells you where you are. The cars, of course tell you where you are. The wardrobe tells you where you are. The hair. I think our reliance upon reality and not doing things in camera to try to fool people, "Oh, we're in a time period," no, just dress and play it. And it's as if we are in that time period, period. Just like in Django, we are in this time period, whichever one you want. It's like all of his films, Inglourious Basterds as well, just enter the time and create an environment that supports it. The better the production design is, the better the cinematography will be.

Something that really struck me about the film when I first saw it, I mean, it's exceptionally well written, but it struck me as possibly Quentin's most directorially or visually driven film to date. And I don't know if that's just coming off of Hateful Eight, which was so talky and dialogue driven, but there's so much visual storytelling in this film. Was that something that you guys had talked about? Was that something that struck you as well?

RICHARDSON: That strikes me as well, yes, because I do agree with you. As I look at the film, it's not what I saw when I read the script. But when I watched the movie, I feel that because there's less dialogue-driven sequences, there's more of this motion between sequences. There's the way he structured the film, which basically is almost a third to quarters of like Leo by himself, or Brad by himself, or Leo and Brad together, or Margot. It's like all those elements have their own separate time that they seem to be pretty equally broken. And because he weaves between them, he's created a road that is allowing us to move very rapidly down. And I think you're right, there's a sense of freedom that he had.

But if you really go back, in my experience with Quentin, if I go back like to Kill Bill, highly visual film, highly visual, because it's so much about swordplay or fighting in some capacity. I mean, it’s more visual than I think people remember. If you go back and watch Vol. 1 or Vol. 2, it's a very visual movie. I would think all the films are pretty visual, but obviously Kill Bill has, if anything, more similarity to Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. But then again, you have to do the Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is close to Jackie Brown and Pulp Fiction. They're all LA-based stories. They fit into a really nice trilogy, and there's a breadth in the way he directed all of those films that is similar. I think, I don't know if you agree.

No, I would agree with that as well. I very much got Jackie Brown vibes from this one, just in terms of kind of that wistfulness of the characters. It's a very sweet film, which I liked a lot.

RICHARDSON: Pretty emotional actually,

It's super emotional, and just very touching and tender, which, after the ending of Hateful Eight, which is just so kind of shocking, but this movie is very different. I think that just speaks to his versatility as a filmmaker. I don’t think he’s made a bad movie. He's clearly one of our best filmmakers and most original storytellers, and the fact that he's able to make such different stories every time is, I think, a testament to his talent.

RICHARDSON: I completely agree with you. We just have to make sure he doesn't retire quite yet.

I know. Can you talk to him about that?

RICHARDSON: Well, I think you should talk to him in the article because I'm going like, "Quentin, you're not going to retire. You've got to do one more film, you promised. There's no retiring and we've got at least one more, so let's, let's not give up yet. You're not making quote unquote old man films," which is what he said he's worried about in the press. But I think in truth Quentin is not going to make an old man movie. I don't know how he would make an old man movie, he's not even an old man.

I mean, he made Jackie Brown in his early thirties, which is insane to me. That's the kind of movie that a filmmaker in their fifties would make. And Jackie Brown is one of his best films, I think.

RICHARDSON: I do too. I love it as well. I love it.

He said he wants to do Bounty Law as a TV show on Netflix now. So I mean, who knows?

RICHARDSON: Yeah, he said that and he also has mentioned the fact that, I think, that's one of the arenas he will walk into. He mentioned Star Trek at a point. I still don't know where that is. He's got to do it. I mean, I would love to see an R-rated version of Star Trek. With Quentin Tarantino dialogue. Hello?

Or just a Quentin Tarantino sci-fi film. I mean that would be great.

RICHARDSON: (Laughs) Yeah, exactly. I think it'd be great. All right, Quentin. Let's see what you do here.

Switching gears for a minute, I was very much looking forward to potentially you doing a Batman movie with Ben Affleck, and now we'll get to see your take on the comic book genre. I was wondering if you could just maybe speak to kind of what drew you to Venom 2?

RICHARDSON: Yeah, well, I mean the thing was, for me, I was looking forward to entering into that arena with Batman years ago with Ben. I thought, well this is something I haven't done that I would love to try to do. And then Andy Serkis, who I worked with on Breathe, gave me a call a month ago and said that he was up for this and would I be willing. And I'd seen the film. I watched it again, then they sent me a script and I felt like, yeah. I would say yes anyway to Andy just because I would say yes to Andy, but I also think it's unexplored yet, and it's going to explode, and this film, I think, will help it explode, because you have a remarkable central character with Venom, but now you've got Woody Harrelson, who's going to obviously make his own little entrance here, and we'll see what else comes in with the Sony Marvel collaboration. I look forward to it. It's a massive change for me, but I'm excited. I think Hardy is one of our best.

Yeah, he's incredible.

RICHARDSON: He never misses. I so look forward to sitting with him and watching him perform. Because he's playing two characters, and that threw me to this in a way. Which is because Venom is really, he's inside. Two people have to cohabitate and I have a few people that are cohabitating in me. I know that they're in there and they come out at times, I'm sure you have friends that come out of you that you like, "Oh no, don't believe that happened. Did I really drink that much tequila and make that phone call? Did I just act that way?" I mean, we have multiple personalities that live within us, but he's got to perform with those multiple personalities. I look forward to that.

Visually, are you kind of picking up from Libatique's work on the first film or are you guys kind of going in your own direction?

RICHARDSON: That actually hasn't been determined in a lot of ways, but I do think that you have to honor what Matty did. You can't not. We're going to use locations that are already established. They're going to be lit in what I hope is exactly the same way, so that you don't feel that there's a disconnect from that film to this film. In terms of the rest, that's yet to be discussed because I haven't yet sat with Andy in London. He's over there now. I don't go until the beginning of September. I'm in the process of getting my visa, and then when I go over all that will be discussed with someone at VFX, with storyboards. We get more into, "Well, how do we think we're going to make this look?"