When you think of Michael Bay movies, there are a number of things that might spring to mind. You might consider his frenetic camerawork, his use of explosions, or even his uncanny urge to place slow-motion close-ups of helicopter rotors in all of his films. But whatever your first thought might be, there is something else about Bay's films you may want to consider: They are just plain mean. Most recently, the ending of Transformers: Dark of the Moon, where Optimus Prime brutally executes Megatron, has resurfaced as a monument to Bay’s misanthropic tendencies. But while that is just a single scene, the title of Bay’s most mean-spirited film overall absolutely belongs to Pain & Gain.

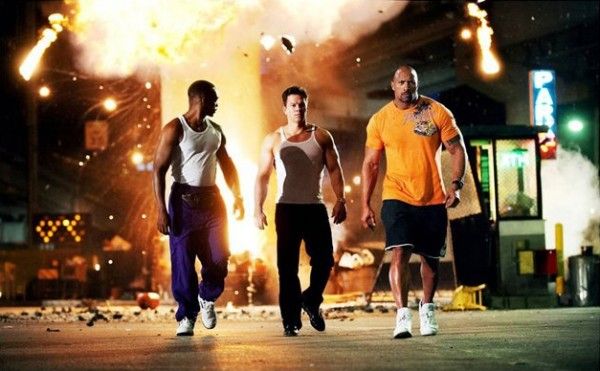

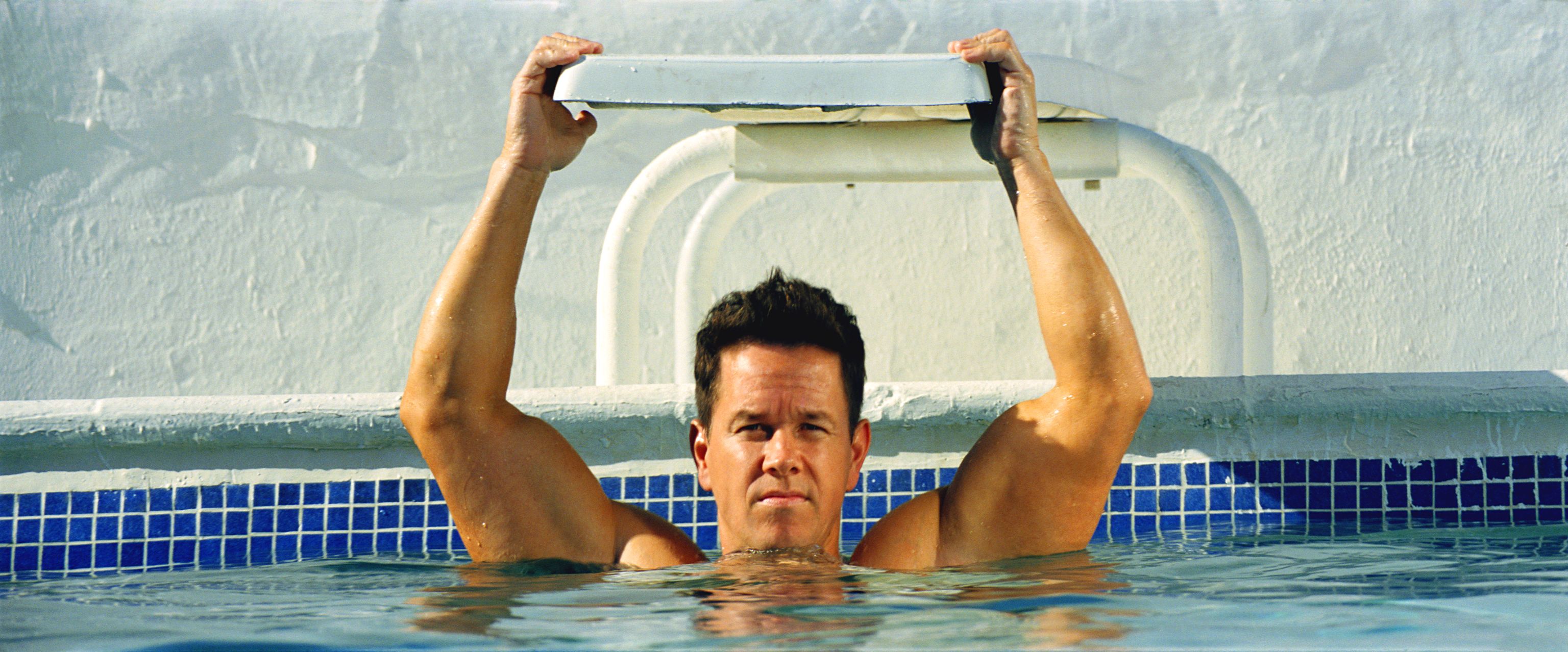

Adapting a true-crime story, Pain & Gain follows Daniel Lugo (Mark Wahlberg), a fitness trainer's self-righteous journey toward fulfilling his idea of the American Dream. In Lugo's view, the world is split into people who do things and those that don’t, and the only way you can get ahead is by holding others back. So when Lugo meets rich client Victor Kershaw (Tony Shalhoub), he doesn’t just want what Kershaw has, he wants Kershaw not to have it. He recruits fellow trainer Adrian Doorbal (Anthony Mackie) and recently released convict Paul Doyle (Dwayne Johnson) to carry out a kidnapping and extortion plot. The premise sounds like it would make for an entertaining film, and Pain & Gain certainly leans into the excess of the lifestyle that Lugo and his gang idolize. However, the reason the film is misanthropic is that Bay clearly thinks as little of his main characters as they think of their fellow humans.

After the trio successfully execute their plan, they gleefully indulge in their stolen millions. Montages of extravagant purchases seem to suggest they are now living the lavish life anyone would dream of having. But the aspect that elevates Pain & Gain beyond some meathead daydream is a tricky balance that Bay is able to strike. While Bay doesn’t exactly condemn the lifestyle Lugo dreams of, he doesn’t glamorize it either. At every turn, the film is clearly laughing at Lugo and his buddies, not with them. Where Lugo tries to justify his entitlement through some warped interpretation of the American Dream, the film is more than eager to point out his contradictions.

Remarkably enough, the film does this primarily through its use of narration. In most films, the voiceover of a particular character is used to inject a dose of sympathy into the film’s narrating characters. The characters use the narration as an opportunity to be vulnerable and express something they wouldn’t say to anyone else, and as a result, they become more humanized. However, Pain & Gain does the exact opposite. Even as several characters take over the narration of the film, Bay manages to maintain a singular point of view.

No matter if it’s Lugo, Kershaw, or even Ed Harris’s private detective Ed DuBois doing the voiceover, the effect of the narration never delves into the inner psyche of the characters. As Lugo and his friends use the narration to try and justify their self-righteous crusade through a myriad of hollow reasons, there is not a single ounce of sympathy wrung out of the narration. Instead, Bay uses the technique to underscore how wildly misguided these souls are. There are moments where, through the narration, it appears as though Lugo is going to admit that he took things too far, but every time, he doubles down on his feeling that he earns everything good that happens to him.

At the end of the day, that seems to be the key reason Bay drives home about why his central characters are so despicable. They all suffer from a mindset that conflates entitlement with their aspirations. Like Lugo, Doorbal and Doyle also feel as though they earn everything good happening to them, but more importantly, they never acknowledge that anything bad that happens is of any fault of their own. Through this, Pain & Gain becomes a cautionary tale of the ultimate weaponization of the American Dream.

And all of this is before mentioning the content of the characters’ everyday conversations. When Lugo and his gang are not physically assaulting their clients, they are spending the remainder of their time together insulting them and making offensive remarks. Another reason the film is misanthropic is that, ironically enough, these remarks are flung out in a nondiscriminatory way. The individual instances of the insults are certainly racist, sexist, or some other type of offensive comment, but the reality of the situation is that Daniel Lugo hates and thinks less of anyone that isn’t named Daniel Lugo. And Bay is more than happy to paint Lugo in the way that he views everyone else. It’s a vicious cycle of misanthropy, but the absurdity of the crimes makes it incredibly entertaining to watch.

Throughout the kinetic camerawork and enjoyment of seeing these massive men flail around when their plans inevitably fail, it’s easy to forget that Bay is indeed trying to tell us something through this story. When things seem like they couldn’t possibly be true, he inserts title cards to remind us that, in fact, all of it is. The events of Pain & Gain happened and, for all we know, could happen again. After all, Lugo was not someone with an extensive amount of resources. He was just a fitness trainer with aspirations and a boatload of confidence.

It’s in his simplistic examination of Lugo that Bay broadens the reach of his cautionary tale. If Pain & Gain is a story about the American Dream gone awry, then Bay is essentially side-eying anyone who may use the American Dream to justify their own actions. Sure, it may be the most pessimistic interpretation of the American Dream ever committed to screen, but the movie impresses because it never feels like homework. The film truly is a blast to watch. Through his highly stylized aesthetic, Bay proved himself to be a perfect match for this story of excess and entitlement. It doesn’t matter which character is doing the voiceover, Bay’s misanthropic point of view completely commands the entire film. And that ability for the film to retain any form of agency, especially against the likes of Daniel Lugo, is a remarkable achievement.