“I think there must be something wrong with me, Linus. Christmas is coming but I’m not happy. I don’t feel how you’re supposed to feel.”

— Charlie Brown, A Charlie Brown Christmas

The quote above is the very first dialogue spoken in the iconic Peanuts holiday special A Charlie Brown Christmas from 1965. It's a very odd way to begin a Christmas special, and especially one aimed at children. Typically, they start with your character that doesn't see anything wrong with hating Christmas, like an Ebenezer Scrooge, or with a character so jacked about Christmas they can't help but to spread holiday cheer to all they meet, cue one Buddy the Elf (Will Ferrell). It is a rarity to see holiday fare that begins with such honesty and frankness, but not if you know the source: creator Charles M. Schulz. The name immediately brings to mind the beloved characters he created for Peanuts, characters like Linus, Snoopy, Pigpen, and, of course, one Charlie Brown. The Peanuts comic strip entertained readers for years, and even to this day the characters are a marketing boon. Yet throughout its history, the cartoons, and, for our purposes here, the seasonal TV specials that sprang from it, would hint at a darker subtext, one that involved obsessive-compulsiveness, narcissism, and depression. And there’s a good reason why it exists: because Charles M. Schulz himself suffered a deep-rooted depression throughout his life.

What Plagued Peanuts' Schulz

To understand Schulz and his work, one has to first understand depression, a mental health issue that is only now starting to truly be understood more deeply. The prevailing attitude simplifies depression as simply being sad and melancholy, something that should be easy to turn off and on, and that is not the case. Having depression is almost unexplainable to those that have never gone through it. You can be happy, you can be sad, but these surface emotions don't express the joyless void inside. It doesn't matter if friends, family, the world at large thinks you are remarkable. You know the "truth," that what you are is not good enough, and if they only knew the truth their opinion would change. Negativity towards you, from a simple "no" to bullying behavior, adds fuel to the fire, and forgiveness is a long shot at best. You do what you can to keep others from falling victim to depression, only knowing it's something no other person should have to live with.

Worse, the relationship with it is toxic: you want to be free of depression, but you can't let it go for fear that doing so takes away the only things that make you special at all. This is what plagued Schulz. He held on to a deep resentment for the school-yard bullies of his childhood, even though Schulz biography author David Michaelis found that Schulz's childhood friends couldn't recall him even being targeted. He found his depression and grief more inspirational than his happiness, refusing to believe the plaudits and love of kith and kin for fear of destroying his creative well. To his credit, Schulz kept a welcoming, kind demeanor at the forefront of his external character.

How Schulz's Depression Shows Up in the Peanuts' Holiday Specials

Schulz's internal struggles would make their way onto paper or screen, sometimes outright, other times subtly hidden, and laying things bare for the world to see made the Peanuts gang all the more popular for it. The Holiday Specials (except for A Charlie Brown Christmas, which we'll get to soon) are a wellspring of mental health depictions in action. Take Lucy's perpetual insistence on Charlie Brown kicking a football. Charlie Brown knows she'll move the ball at the last second, she always moves the ball at the last second. Yet somehow she talks him into trying, like in It's the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown when she shows him a signed document assuring him that she won't pull the ball away. Invariably she does, in this case because the document wasn't notarized. This is fed by Schulz's resentments of those who've wronged him: he doesn't believe they've changed, they convince him they have, but leopards can't change their spots, as they say, and they reopen the wounds. Charlie Brown gets rocks in his treat bag at Halloween, and no Valentine's Day cards in Be My Valentine, Charlie Brown, a karmic assurance that his negative self-worth is correct. Charlie Brown takes the blame for ruining everyone's Thanksgiving in A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving, even though he literally had nothing to do with how the day played out. He's a loser, a blockhead, stupid, and more.

'A Charlie Brown Christmas' Is Schulz at His Most Vulnerable...

It's A Charlie Brown Christmas, however, that deals most directly with depression: having it, misunderstanding it, and labeling it. Charlie Brown's honest assessment at the beginning of the program is followed by a series of events that only serve to justify how he feels about himself: no Christmas cards to show he's thought of, laughed at by his peers, a feeling of how everything he touches is a disaster.

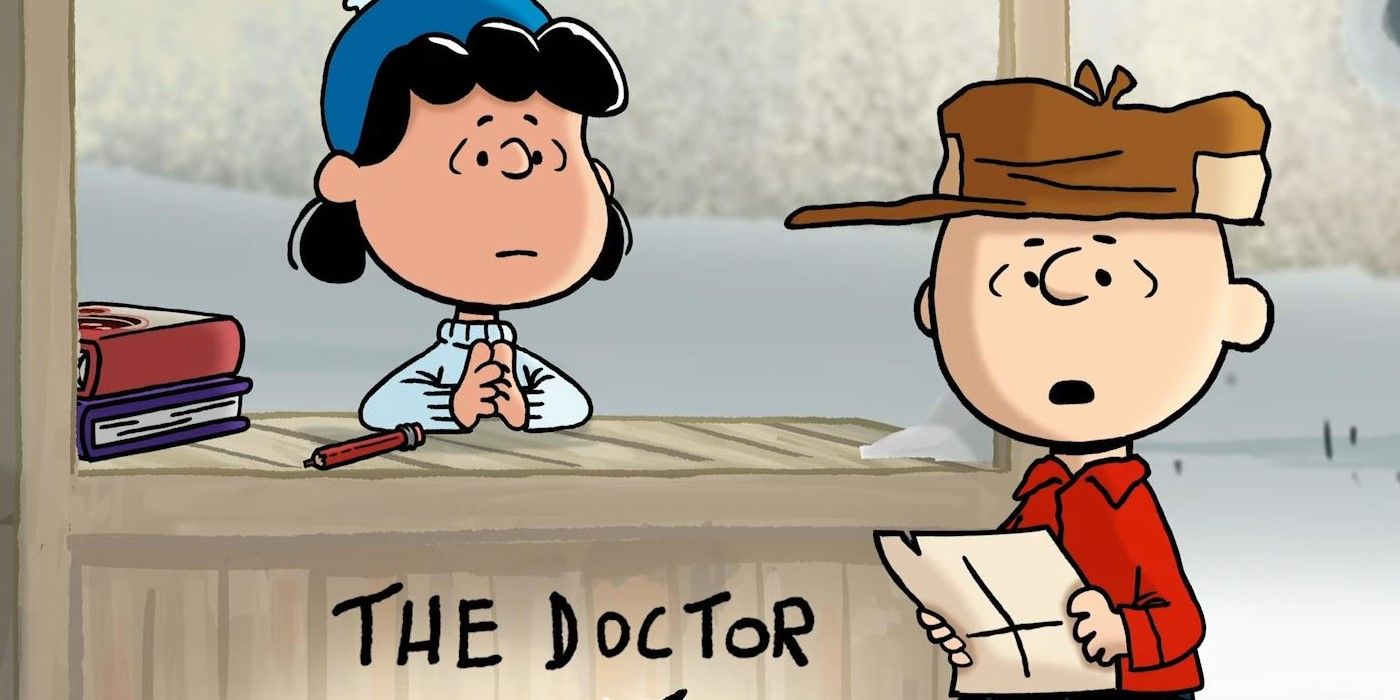

Additionally, Schulz does a masterful job of showing how depression is misunderstood in the special. Linus says, "Charlie Brown, you're the only person I know who can take a wonderful season like Christmas and turn it into a problem," a clear shot at those who believe it can be turned around. Lucy's vain attempt at understanding is her linking depression to not getting the gifts she wants at Christmas. It's through Lucy how we also see how depression is handled by so-called professionals. Her psychiatrist booth is a means of getting money, and her insistence on giving Charlie Brown's depression a label shows just how little was known at the time about depression as a mental health issue on its own.

... But Also At His Most Hopeful

What the revered classic does better than its kin is to show Schulz's hope in spite of it all. Schulz's Christian faith was something he found strength in, and it's through Linus' telling of the Christmas story that two very important things happen in the story. First, Charlie Brown finally understands what Christmas is about, finally "gets it." Secondly — and this is a very subtle touch — it is the only time Linus let's go of his security blanket, showing that even he can find security apart from the tangible. Then there's the poor, pathetic Christmas tree, the one that prompted the backlash and taunting of his friends, but ultimately the one that pulls the group together to turn it into something beautiful, just as the poor, pathetic and depressed soul can also become something beautiful in the end.

If you or a loved one are struggling with depression, please reach out. There is help. In the United States, call 988 to access the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline. In Canada, call 1-866-585-0445 or text WELLNESS to: 686868 for youth, 741741 for adults.