Throughout his career, Paul Thomas Anderson has made films that are, at the very least, interesting. Sometimes they demand more than one viewing to even comprehend what the director was going for, and they don’t always click together, and yet he finds a way to find a unique spin on a traditional drama and warp it to a completely new purpose. His latest film, Phantom Thread, has the lush, luxurious feel of a Merchant-Ivory production, but seething beneath the surface is a dark and twisted tale of obsession, seduction, and destruction with regards to artists and their art. Although the film suffers from similar problems to Anderson’s recent fare, Phantom Thread remains compelling thanks to captivating performance and exquisite craftsmanship.

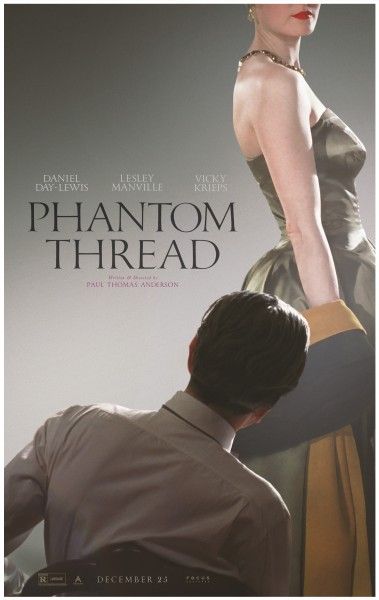

Reynolds Woodcock (Daniel Day-Lewis) is an esteemed fashion designer building exquisite dresses for London’s wealthiest women. His work consumes him, but he’s helped by his sister and confidant Cyril (Lesley Manville). Feeling stressed out by work and smothered by a former lover, Reynolds makes his way to the countryside where he meets Alma (Vicky Krieps), a young waitress whose perfect proportions dazzle the fashion designer. They begin a twisted relationship where Reynolds sees her as another living mannequin, but Alma resolves to be more than something easily discarded, no matter the cost.

Phantom Thread, like most of Anderson’s filmography, invites numerous interpretations, although it’s clear the themes of his film deal primarily with artistry as well as gender. Woodcock (the name is not an accident) is surrounded by women—his sister, Alma, his clients, and the group of ladies who do the actual tailoring of his designs. He’s also obsessed with his late mother, dreaming about her and revering how she taught him his trade. But this dependency on women is also balanced by an ingratitude. Woodcock constantly takes all the women in his life, even his clients, for granted. He would be lost without them, and yet with perhaps the exception of Cyril, he treats them as disposable and replaceable.

Alma is sharp enough to read the room and resolves not to be so easily cast off, and watching her spar with Reynolds is delightful and intriguing. Anderson makes a meal of the gender dynamic, what powerful men expect, and how women must fight to be treated as essential, whether it’s through sheer force of will like Cyril or through cunning like Alma. Although Day-Lewis may be the biggest “name” in the cast, Phantom Thread is really held up by three actors, and the relationship between Reynolds and Alma is the core of the movie.

But where that relationship really grabbed me wasn’t so much in the gender dynamic (although that aspect is fascinating), but how it represents the relationship between artist and art. If you view the film through the lens of Reynolds as artist and Alma, his model and muse, as art, you see an intriguing theme take shape about how much art demands from an individual and what a wondrous and torturous process that can be. Anderson displays that give and take with equal measures whimsy, exhilaration, frustration, and cruelty.

These two themes work hand-in-hand, elevating Alma to more than a canvas or a symbol and turning her into a person with individual thoughts and goals even if those thoughts and goals always relate back to her place in Reynolds’ life. The interplay between the themes—gender and creativity—make for a film that’s constantly interesting if not always emotionally moving (although the film is certainly funnier than expected, constantly trotting out a wry sense of humor). It’s a problem Anderson had run into previously with both The Master and Inherent Vice, movies that are so tightly wound and introspective that they fail to breathe.

Thankfully, Phantom Thread is a more enjoyable experience than those two films (being about a half-hour shorter helps), and it thrives thanks to the craft and performances. The film is a marvel to behold, and would garner no objections if it earned Oscar nominations for Best Costumes (Mark Bridges), Best Score (Jonny Greenwood), Best Cinematography (Anderson), and Best Art Direction (Denis Schnegg, Chris Peters, Adam Squires). As for the performances, Krieps holds her own against Day-Lewis, which is saying something when you consider that Day-Lewis is one of the greatest actors of all-time. Manville is a force of nature, holding all the power in every relationship but never flaunting it.

For Day-Lewis, it makes sense why he chose for this to be his last performance. It’s not that it’s his best work, although it’s at the same level of excellence we’ve come to expect from him over the decades (no one plays a raw nerve like Day-Lewis). In a recent interview with W, Day-Lewis said of Phantom Thread, “I do know that Paul [Thomas Anderson] and I laughed a lot before we made the movie. And then we stopped laughing because we were both overwhelmed by a sense of sadness. That took us by surprise: We didn’t realize what we had given birth to. It was hard to live with. And still is.” Because Anderson isn’t the only artist involved in making this film, and I believe that Day-Lewis sees a kinship with Reynolds, a man so devoted to his work that it corrupts everything else in his life. Phantom Thread is a story about the toll art takes on artists, and Day-Lewis, who completely gives himself over to his roles, is likely well aware of the cost.

The irony of Phantom Thread is that even though it centers on the emotional cost of creating art and the selfishness of men (specifically male artists), it’s not a particularly emotional movie. And yet, like a meticulously crafted dress, it may not move or breathe, but we still marvel at its exquisite craft and stunning design.

Rating: B