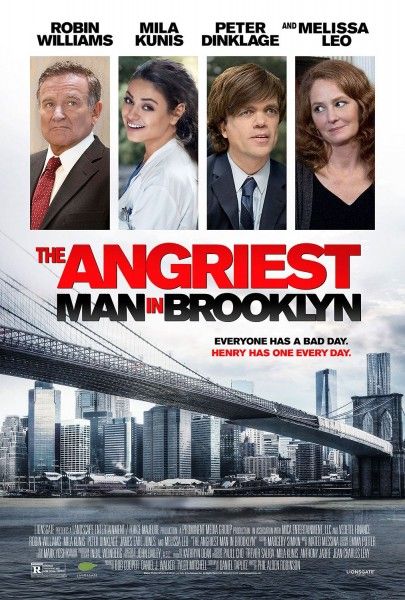

Opening May 23rd, Phil Alden Robinson’s dark comedy, The Angriest Man in Brooklyn, marks his first directorial effort since his 2002 action thriller, The Sum of All Fears. Robin Williams stars as Henry Altmann, an unhappy man who is suddenly forced to reassess his life after his doctor (Mila Kunis) gives him an unexpected diagnosis. What starts out as a bad day turns into something far worse as he struggles to right all his wrongs in what he believes are the final moments of his life. The impressive cast also includes Peter Dinklage, Melissa Leo, James Earl Jones, and Hamish Linklater.

In an exclusive interview, Robinson spoke about what inspired him to direct again, why he was drawn to the riskiness of the project and thought it was a gamble worth taking, how he attracted the strong cast and what the actors brought to the film, what he discovered making his first indie film, the challenges of finding the right tone, the contributions of DP John Bailey and composer Mateo Messina, what he learned about the creative process from director Sydney Pollack, his thoughts on the 25th anniversary of Field of Dreams and Kevin Costner’s performance, and his cool, upcoming projects including The Jazz Ambassadors with Morgan Freeman, two recently completed spec scripts, and a pilot for a new cable TV drama. Hit the jump to read the interview.

Question: How did this project first come together for you?

PHIL ALDEN ROBINSON: There was an Israeli film, The 92 Minutes of Mr. Baum, that an American producer had bought the remake rights to, and he hired Dan Taplitz who’s a wonderful screenwriter. Dan had had a similar experience to the main character in the film. When he was in his twenties, he was given six months to live. Thank God that turned out not to be true. He’s fine now, but he did in fact have a similar experience and related to the dilemma of the character. He did not watch the Israeli film. Neither did I. I’ve never seen it. He said, “I really want to write this, mostly because the premise is so powerful for me. I don’t want to have someone else’s take in my head. I really want to do my own.” So, he wrote this. This was long before I came on the project. When he finished the script, Bob Cooper, the producer, sent it to me. I’ve known Bob a long time and he said, “I’ve got this great script and I want you to read it.” I was on page 3 or 4 when I realized that I had already laughed and cried, which is pretty great. I kept thinking, “Oh please let the rest of it be as good as this.” Sometimes your heart gets broken when you read a screenplay, and it’s got a great premise, and then it just falls apart. This one kept getting better. It kept surprising me.

I always look for that in scripts. I want to continually be surprised and it did that. When it was over, I had a bunch of reactions, and not just to the premise of the essential question of what would you do if you found out that you only had a certain amount of time left to live, which is very powerful. It’s a question we should all ask ourselves, because it’s healthy to think about, “Well then, why don’t I just do that?” I had another issue which was I’d been thinking a lot about how much anger there is in our culture and our society today. The public discourse has gotten really ugly and I think much to our detriment. When I read the script, I thought, “Thank you. Somebody wants to write about this. Somebody wants to start a discussion about what I think is a real national problem, both political and personal.” He did it in a way that never preaches. He never talks about the society at large, and he does it in a way that is extremely entertaining. The script is hilarious and it was very touching, but it did point out how poisonous and self-defeating anger is and how important it is to figure out how to get rid of it because it’s just toxic. That’s one of the big reasons that I was attracted to this, plus the fact that, as I say, it was hilarious, moving and surprising. I thought it had great roles for actors and this would be really fun to do.

This film marks your first film in 12 years since The Sum of All Fears. What was it about this particular story that inspired you and made you say, “I’ve got to direct this”?

ROBINSON: It was really the screenplay. The screenplay was so funny and touching, and it was about something that I cared about. I read a lot of scripts and many of them are terrific. There are a lot of great writers out there. A lot of them I would feel, yeah, it’s wonderful, but it’s not a subject that I want to devote a year or a year and a half of my life to. Other times I’ll read something and I’ll think, yeah, I really like this, but there would be other people who would do this so much better than I would that I shouldn’t take up somebody’s time by saying let me do it. This one just felt like a match. I liked the issues. I liked what it was about. I liked what I thought I could bring to it. Also, I try not to repeat myself. Every director gets offered versions of films they’ve already done, and this was something I hadn’t done. As a friend of mine said to me once, “You get bored easily, and that’s why you do that.” There may be some truth to that. I thought the tone was something I hadn’t done. The subject was something I hadn’t done. The style was something I hadn’t done. It’s a relatively low budget, independent film, and that’s kind of the new world, and I wanted to experience that, too. A lot of things about it felt fresh to me and felt like it would keep me on my toes, keep me scared, and keep me focused.

You’ve got a fantastic cast with Robin Williams, Peter Dinklage, Mila Kunis, Melissa Leo and James Earl Jones. Can you talk a little bit about how you attracted these people and what they brought to the film?

ROBINSON: Great question. One of the joys of doing a film like this from a great screenplay is that actors can see on the page that a lot of thought has been given to each character and that there’s some juicy stuff that they can sink their teeth into. And so, it’s relatively easy to attract really good actors to a script like this. That’s how good it is.

Let’s start with Robin. What’s interesting is my agent also represents Robin. One day, right after I said I wanted to do this, my agent said to me, “You know, it’s really amazing, I asked Robin when we signed him, ‘What kind of films do you want to do?’ and Robin said, ‘Do you know a screenplay called The Angriest Man in Brooklyn?’ I said, ‘Know it? I represent the director,’ and he said, ‘Well that’s what I want to do.’” It was something that he’d been tracking. He was aware of it. He’d read it at some point and he was waiting for it to go. When I heard that, I thought this is great, because I think he’s one of the great talents of our time. He’s an original talent. There’s no one else like him. He’s a wonderful actor, too. He’s Juilliard trained. He started as an actor. We sat down and talked about the script. We were both in sync, particularly for his character never letting the audience catch us going for the joke, that we had to approach his character as if it was a drama and let the laughs come from what’s inherent in the screenplay, but not force any from his character’s point. We break that rule for other characters, but not for him.

For me, what he brought was this tremendous lifetime of skill in performing because it’s a very tough role. He’s also a very courageous performer, and what he learned in comedy informs his drama. As a comedian, he was never afraid of anything. He would just go as far as he possibly could with a premise. What’s great with this role for an actor is I needed somebody who would not be afraid of the anger and who would not ever try to simultaneously say to the audience, “But love me.” He needed to be the angriest man in Brooklyn. He needed to be somebody that at the beginning of the film you think is unfixable, that he’s just so toxic, and he was not afraid of that. There are a lot of performers who would have tried to have mitigated somehow, so that they’re not quite so bad. He went all out and that’s one of the reasons that his performance is so compelling. I can’t take my eyes off of him when he’s on screen. I find it magnetic and very involving, and along the way, he’s also really funny. It’s a real tour de force.

And then, there’s Peter Dinklage. I keep a list. For years, I’ve kept a list. It’s a fairly short list. When I see somebody in a film or on stage where I think, “Oh my God, I can’t get that person out of my mind,” I just put them on this little list of some day find a role for that person. When I saw Peter in Living in Oblivion, and that was years ago, a great little independent film that I think was his first film, he went right on the list. I just love this guy. He’s amazing. When I was analyzing the role of the brother, I felt the salient feature here is that he’s afraid. He’s fearful. When he gets in the taxi cab with Mila, he’s afraid. I thought that’s an interesting thing to hang the rest of the character on. His older brother is Henry Altmann, and that could be one of the reasons, because he has this domineering older brother. For some reason, I thought I’ll bet Peter could do that. I went to New York and I had lunch with him. We met and had a wonderful time. He’s a great guy. He’s really smart and just a lovely guy to hang out with. Everything I’ve ever seen him do he’s been brilliant in. What a great opportunity to spend time with Peter Dinklage and make a movie together at the same time. That was a lot of fun.

Mila is also very good in the film. It’s interesting. Mila is what I call a fast actress. She can access the emotions or the colors that she needs for a scene so quickly. She doesn’t need a lot of prep time. Some actors need prep time for each shot, but not her. She can get right to it. There’s a great example. There’s a scene where she’s on the bus and she’s crying. This is how low budget and indie we were. We shot that bus as we were actually moving from one location to another. We had finished the James Earl Jones scene in the morning. We had to move the whole company to where the bus breakdown was going to be shot. Rather than put everybody in vans, we said as long as we’re traveling, let’s put Mila and the camera on the bus as we go to the next location and shoot this scene on the way so that it doesn’t take any time out of the day. And so, we were on the bus literally going to the next location, and I saw that we were going under an overpass, and I thought, “Oh this will be cool because the bus will be dark, and as it comes out of the overpass, it will be light.” I just turned to the cameraman and said, “Just roll, right now,” and I said, “Mila, action!” We were dark and we panned down from the ceiling. Three seconds later, when we come to her and the lights come on, she’s crying. I thought that’s real skill. That’s an amazing gift.

Were there any surprises or things you wish you’d known on day one of production?

ROBINSON: Well, they have to do with business. Everything I’ve ever done has been for a studio. I wish I’d known that in indie filmmaking your budget is not actually how much you have to spend on the movie. There are a lot of other things. Everybody that’s put up money gets fees. Those are in the budget, and bonds and contingency and insurance, all kinds of things, so that the number you think you have is not actually the number that you have. I wish I’d known that, but now I do. Mostly, it was really fun shooting in New York, and I’d heard horror stories. I’d heard people saying, “Oh my God, it’s so hard to shoot in the streets of New York,” but I loved it. It makes me wish I’d done it more and I’ll certainly want to do it again.

How many days did you shoot and how was it dealing with the budget constraints of an indie film?

ROBINSON: It was 27 days. It was fast. I never talk about budget or actual numbers, largely because there actually is no single number. The number changes a lot as you go, so it’s hard to know. Is it the budget that we started with? Is it the budget that we ended with? I don’t know what we ended up with. There’s a certain point in the production where I stop paying attention to that bottom line. This is something I learned long ago dealing with studios. If I say to a studio, I need another $300,000, I’m going to lose that argument. But if I say, “For these two days I’ve got to have a crane, and we want to move the location, and here’s why,” sometimes you win those arguments. So, I just stopped paying attention to the numbers because they weren’t helpful at a certain point.

The film focuses on a very serious dilemma, but it’s also life affirming and has a sense of humor and humanity. Was it a challenge finding the right tone?

ROBINSON: Oh yes. For me, that was the hardest thing to do and it was the biggest risk we took. I haven’t talked about this yet, but you’ve asked the right question so I’ll tell you. The traditional, conventional wisdom is that if you’re going to mix comedy and drama, you have to find compatible tones for each. If your comedy meter is set to 7, then the drama meter has to be set to 7, and then the story has to be 3. You’ve got to find ways that they’re compatible and they’re consistent. My instinct was that’s an old rule that probably works a lot of times, but for this movie I wanted to see if we could break that rule. Consequently, there are scenes in which the drama is very intense and other scenes where it’s subtle. There are scenes where the comedy is very broad and other scenes where it’s gentle and observational. It could throw some people because that’s not the way it’s supposed to be done, but as we were doing it, I thought this is how life is. Life doesn’t always have compatible moments. It’s not always fine-tuned. It jumps around. Sometimes it jumps around in the same moment. It was an interesting experiment to see if we could break this rule and still have a film that was coherent.

Can you talk about the contributions of your DP John Bailey and your creative team?

ROBINSON: John Bailey is one of the legendary cinematographers and he’s been a friend for some time. We’ve never worked together before, but we had traveled together. We’re both on the board of the Academy and we were on a trip to Africa. About two or three years ago, we went to Kenya and Rwanda. We were teaching at film seminars and we had a great time. I got to watch him up close talking about the craft of film. There’s nobody more knowledgeable than John. He’s an intellectual, an artist, and a real scholar about film, film history, and film technique. When this film came up, I thought this would be a fun opportunity. I know that John has a place in New York so it’s easy for him to go there. We talked about it and he said he’d love to do it. What I didn’t realize that was a great benefit was John’s previous three or four films were shot digitally, so he was very up on the latest cameras and equipment. I’ve never shot digitally. I’ve shot little home movies, but certainly not a feature.

What I learned that was so great was first of all, he’s a great collaborator. We sat down and had wonderful talks, scene by scene, sitting in my office talking about how we wanted to do this. We had a very subtle plan for the overall look of the film and when we were going to be hand-held, when we were going to be Steadicam, and when we were going to be on sticks. We had this all worked out, and we started shooting, and it was just phenomenal. There was nothing I could throw at him that he hadn’t already done. I’d say, “I’ve got this weird idea for some coverage of this scene,” and he would say, “Oh yes, well in 1936, there’s a French director who did exactly that.” He was phenomenal and we never waited more than 20 minutes for a shot. He’s so fast. You can’t give him a problem that he’s not already solved. He travels with a very light equipment load.

The crew was mostly young kids, and they were getting the great film school lesson of their life. It was like 27 days with John Bailey. He would show them how to do stuff, and it would be fast, and it would look good. It was terrific. It was really fun. We never could have gotten through the schedule without somebody that skilled. We used the Alexa. I had said to John there’s no money in the budget for a second unit and I really want to have a lot of street life of Brooklyn, so he got Sony to give him a brand new Prosumer camera. It’s a little hand-held thing. If we had a few minutes here, we’d just walk around the corner and shoot stuff on the street, and then if we were able to wrap a half-hour early, we’d go to some other neighborhood and shoot around the street. Consequently, by the end of the film, we had a ton of great Brooklyn street life, and so, in the editing room, it was really wonderful. We were able to constantly create what we call these little pods, little montages, and quick cuts all around Brooklyn of people, cars, buildings, and traffic. It helps keep the film alive and it was fun to do.

You made some interesting musical choices for the film. How did Mateo Messina’s score complement the story?

ROBINSON: Mateo is wonderful. He’s young and extremely talented. He came in pretty late in the process. We had experimented with a few different types of temp scores. You get in the editing room, and you’re cutting the scenes, and you start messing around with cutting music from other movies in. We were finding that it was very difficult to find the right tone. Mateo came in, and I said to him, “Look, these are my overall thoughts. The movie is about a ticking clock and I’d like it to be mostly percussion instruments, and you can have melodic percussion instruments. I don’t know if any keyboard or marimba is the thing, but I’d really like it to be percussive so there’s always a pulse to the score. What I didn’t know is that he had originally been a drummer, so this was right up his alley. I thought he did a great job. He’s so gifted and inventive and he’s fun. He loves his job and he’s really good at it. Everything he did, he enjoyed doing. He lives up in Seattle. He has a little studio up there, and he would bring musicians into the studio day after day and try new things. He’d email them down to me, and then he’d come down and we’d look at the film together, and he’d go back up there. Then finally the parts with orchestra, which is more towards the end, we recorded up there. I went up and he hosted this session with these wonderful Seattle musicians who were terrific. He was fun to work with. I really enjoyed him.

How does the final film compare to what you originally envisioned?

ROBINSON: It’s always different. You’re so right to ask that because it took me a long time to learn this. Early in my career, I would always just want to open my veins at the end of the shoot and say, “Oh my God, I didn’t get on camera what I had in my head.” I remember after Field of Dreams being kind of disillusioned with the process of directing, because as a writer, when I finish a script, it’s exactly what I want it to be. When I finish directing, it’s always different. I didn’t know how to process that. I met Sydney Pollack and I said to him, “Can you help me out here? I finished the film and it’s nothing like what I had in my head,” and he said, “It never is.” I said, “Never?” He said to me, “Not in rehearsals, not on the set, not in the dailies, not in the editing room, not on the mixing stage. Never.” (Laughs) I thought if he feels that way, I should just grow up and stop complaining because it doesn’t get any better than that.

It was a maturation process for me. It helped me see that directing is a very organic process, and what you have at the end cannot simply be the result of what you had in your head, because you’ve gone to the ends of the earth to get the best collaborators and they’re going to change it. They’re going to have an effect on it. Your job is to try to direct them so that the effect they have is in keeping with the overall vision that you have. If that works, then you’ve got something far better than you could have done yourself. If you’d been able to transfer the movie in your head to the screen, it wouldn’t be as good as what these people had helped you make it. Once I realized that, I was fine. It’s interesting. In this film, there are scenes that are much funnier than I thought they would be. There are scenes that are much more dramatically moving than I thought they would be. On the whole, as good as the film was in my head, I’m more pleased with this one. I must say I get surprised when I watch it. I see things and I think, “Wow, that doesn’t look like what Phil Robinson would do.” (Laughs)

That’s what’s scary and what’s wonderful about the creative process. At the end of it, you may have something that is awful. That’s the risk you take. And this, to me, is a risky film. There will be people for whom the anger is just ugly, and they don’t want it and they won’t like it. I accept that. Fortunately, most people I’ve shown it to really like it, but I get that this is risky. We’re taking a risk here. It’s edgier than people might expect from seeing my other stuff, although I did nuke Baltimore so it shouldn’t be a total surprise. I like the riskiness of the film and I think it’s a gamble worth taking.

Did you test screen the final version with various audiences?

ROBINSON: No. Very early in editing, we had a couple of test screenings just to see what direction we were going in, but we’ve never tested the final version. It’s the first time I’ve done that, so that’s also a little bit unnerving, but we’ll see how it goes. It’s a hard film to sell because of the mix of comedy and drama. I have no idea how people perceive it based on either the trailer or the ads, but I’m hoping they realize that it’s got a lot on its mind and it’s also really entertaining. It’s a very unusual ride and the performances are magnificent. James Earl Jones steals the movie. (Laughs) I like to think he’s delicious in this.

It’s the 25th anniversary of Field of Dreams which you adapted to the screen and directed. How do you feel when you look back on having made a film that has resonated in such a powerful way with so many people?

ROBINSON: It’s really amazing. It’s like you hope when you do anything creative, and I’m sure every painter or novelist or poet feels this way, that this one is going to last, that it will outlast you, and that people will be talking about this for centuries. Of course, you know that that’s hard to achieve so you kind of put that out of your head. When we made the film, we thought it was good, but it never occurred to us that it would have this kind of life. It’s very gratifying. It’s hard to draw lessons from because it’s such a crap shoot out there and you can’t plan this sort of thing. For some reason, it hit a zeitgeist that touched people in a way that they weren’t expecting to be touched, I suppose. It did for other people what the book did for me, and that was really what I’d hoped for all along. I’ll never be able to see the film the way an audience will see it, because I know how it ends. All I can think of is the first time I read the book. I was just so moved and so fascinated by it. I thought it would be great if the film could do that. It’s a rare thing, and it’s an unexplainable thing, but it’s lovely and it’s very gratifying.

Kevin Costner recently spoke about Field of Dreams at the press day for Draft Day and revealed his thoughts on its impact and how it went beyond being just a film about baseball.

ROBINSON: Some of my favorite reviews were the French reviews, because the French have no use for baseball, and they were glowing. I just thought that’s great that they were able to [appreciate it]. A lot of the foreign reviews are very good. They all came to the same conclusion that it had nothing to do with baseball. That really pleased me that people were able to see past the American sport and get to the life underneath it. When you speak of Kevin, every time I see the film, I’m very proud of what I did on the film, but I think he had the hardest job of all to play a character like that. We have to believe that he believes he has to follow this voice and we also have to believe he’s not crazy. That was a really hard thing to pull off and he did it brilliantly. Every time I watch the film, I look up and I wonder if I can see how he did that, but it’s just invisible.

What’s next for you? What are some of the cool projects that you’re developing or working on now that you’re excited for audiences to see?

ROBINSON: I just finished a script written on assignment. I also had a couple of spec scripts sitting in my drawer for ten years that I’ve never been able to get out of my head, and I just finished them. I can’t really talk about what they are, but they’re very, very unusual, and so we’re going to take those out and see if we can get a ride on them. And then, I’m also about to start writing a pilot for a cable network. It’s a drama, but it’s all too early to talk about. That’s still very under wraps. I’m sure we will talk about it one day. I hope so. It’s a busy time. It’s a good time.

What’s the status of The Jazz Ambassadors? Is it still in development with Morgan Freeman attached?

ROBINSON: Yes. That’s active. I just finished a draft and Morgan is very happy with it. We’re trying to set that up. He’s going to play Duke Ellington.

Do you plan to direct?

ROBINSON: I hope so. Yes.