When Pretty Little Liars premiered on ABC Family in the summer of 2010, teen television had only just finished (to adopt a possibly labored metaphor) memorizing its freshman year locker combo. Critical aughts darlings like Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Freaks and Geeks, and Veronica Mars had demonstrated just how inventive and artfully edgy stories about about teens on television could be, and primetime heavy-hitters like The O.C., Gossip Girl, and Glee had proven how passionate (read: lucrative) the audiences who tuned in for those stories could become. It wasn’t until the end of Pretty Little Liars’ inaugural episode, though, when the crane swung high over the Liars’ heads after they read out the last line of A’s iconic first group message like some kind of funeral-chic Greek chorus, that viewers got their first real glimpse of the kind of boundary-pushing, social media-savvy storytelling that would come to dominate teen airwaves by the end of the decade.

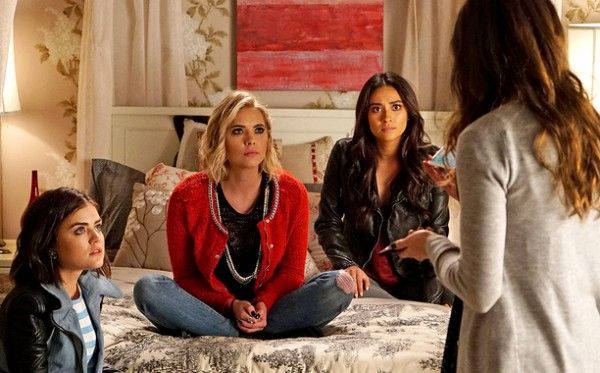

Ostensibly the story of four teen girls — Hanna (Ashley Benson), Spencer (Troian Bellisario), Emily (Shay Mitchell) and Aria (Lucy Hale) — whose suburban Pennsylvanian lives are upended by a mysteriously omniscient stalker named A, who may or may not be the ghost of their dead best friend, Pretty Little Liars was a masterclass in audacity. Adapted from Sara Shepard’s soapier Alloy book series of the same name, the show was originally pitched as a teen take on Desperate Housewives. However, as series creator and showrunner I. Marlene King recently noted when guesting on the first episode of The Pretty Little Wine Moms rewatch podcast, pilot director Lesli Linka Glatter helped steer the show’s tone more in the direction of David Lynch’s weird and moody Dead Girl cult classic, Twin Peaks, a choice which ended up having a positive (if not more than a little eerie) snowball effect on the show’s creative direction for the next seven years. Cue the title sequence featuring a dead girl getting dolled up by a mortician; cue an endless string of dead bodies who got in A’s way; cue every Hitchcockian allusion you can think of. Cue, in other words, audacity.

To be sure, basements full of ominously chorusing broken dolls, threatening messages rolled up in tiny scrolls stuffed between a person’s molars and adderall-induced film noir fever dreams (see above) might not sound out of too left field today, where the teen television landscape has an active catalogue that runs 70+ series deep. But back in 2010, PLL was one of only a dozen teen series on the air, among which only The Vampire Diaries might have hoped to match it in storytelling recklessness. In that context, escalating A’s absurd reign of terror season after season would have been thrilling enough; for Pretty Little Liars to do so while simultaneously finding space to frame female friendship as a platonic love story, to break queer ground by treating Emily’s lesbian relationships with as much (or as little) care as the other Liars’ straight ones, and to call foul on the kind of patriarchal bullshit that most devastates modern teen girls — it was, in a word, groundbreaking.

It was also trend-setting. Because while teen television has taken some beautifully wild left turns in the past few years—Netflix’s On My Block and Daybreak, Apple TV+’s Dickinson, and OWN’s David Makes Man come top of mind—it’s illuminating to take a quick inventory of the things we take for granted about teen television today that can be traced back to Pretty Little Liars:

- Dig Riverdale’s stylized murder mystery shenanigans? PLL was there first, taking inspiration not just from Twin Peaks, but also from (among countless others) Alfred Hitchcock, Robert Chandler, Hedda Gabler, Max Ophuls, and even Edward Hopper.

- How about MTV’s short-lived Sweet/Vicious, and the righteous stand it took against campus rape culture a full year before the #MeToo floodgates burst? Well, aside from making Hanna President of the Man Haters club in the aforementioned noir episode, PLL literally drove a car through one Liar’s abuser, and chopped another’s head off. (Bonus points: Hanna saying ACAB before it was mainstream.)

- Or look at the kinds of steady, idiosyncratic female friendships that form the core social dynamics in series like Faking It, SKAM (in all its iterations), Derry Girls, and Betty — that’s for sure courtesy of the Liars, who walked (that is, spent seven seasons of finding meaning through autonomy only to be shuffled off into lazy marriage-and-babies happy endings) so that the next generation could run. (Or, in Betty’s case, skate.)

- How about all those new international Netflix Originals your teen cousin’s in love with—puzzle box shows like E L I T Ǝ, Blood and Water, and Control Z? PLL to their cyber-mystery, class warfare core, ever last one. (Just, you know, in other languages, with significantly more diversity.)

- And that Zendaya vehicle, Euphoria, which HBO framed as television’s first "real" dive into the nightmare that is being a high schooler in the Age of Social Media? Friend, not only does Euphoria owe a debt to every text-based terror A unleashed on Rosewood’s prettiest little Liars years before any meaningful anti-cyberbullying legislation passed on any level in the real world, but Zendaya’s Rue and Hunter Schafer’s Jules owe a romantic debt to Emily and Maya and Paige and Alison for making theirs a love story not about two girls, but rather about two people. Two broken, hurting people. In 2020, that’s what we call progress.

Naturally, there’s plenty about Pretty Little Liars that doesn’t hold up to scrutiny upon rewatch in this, the Era of Our Cultural Reckoning. This is especially true in the first season whose tenth anniversary we’re celebrating today, which is both suffocatingly fatphobic, and possibly even less aware than it realized of how inappropriate the power (and age) gaps were between several of its central romantic pairings.

Later seasons have their own well-known failures, too—the trans villain debacle of Season 6; the ludicrous defanging of one of teen history’s greatest villains in Season 6 and 7; the indefensible redemption of Ezra Fitz from Season 5 on; the aforementioned marriage-and-babies happy ending; just an overwhelming lack of real diversity. But even with those flaws, PLL leaves a legacy. On the question of non-villainous trans visibility, Euphoria, Faking It, Control Z, The Fosters, No Good Nick, and even NBC’s Good Girls have made strides in including trans characters without falling into a storytelling trap that might ask them to turn villainous.

Diversity, too—of race, religion, ability, country of origin, gender identity, and sexuality—has become something teen television has become at least more aware of needing to incorporate, even if it’s not yet always done well across the board. Happy endings, meanwhile (at least, of the marriage-and-babies variety), are increasingly passé. Similarly, the very idea that a series today, fully post #MeToo, might put forth a teacher as a viable romantic interest for an underage lead — even one as young and charming as Ezra Fitz — it’s laughable. (That said, should Euphoria peel off down that path in Season 2 in the name of raw edginess, I won’t be particularly surprised.)

All that said, as we celebrate Pretty Little Liars’ tenth anniversary—here, now, while a world that was already broken is being shattered further to make room for something new to grow in its place—it seems obvious that the series’ greatest legacy has little to do with whatever other shows have joined the teen television ranks since, and everything to do with what lessons we, as viewers, might be able to take from the Liars themselves. Because if there was one thing Hanna, Spencer, Emily and Aria mastered over seven long seasons of A doing their worst to break them down and tear them apart, it was how to go about the stuff of everyday life even as the world burned around them. They did it by holding on to each other; by finding moments to laugh, even in the darkness of the dollhouse; by building solidarity with their community; by never losing faith that they would beat A in the end.

We aren’t lucky enough to have one A (or even two, or three, or four and an evil twin) to set ourselves against in this moment, but taking a break this past week to watch the Season 1 Liars learn how to love each other again, and how to build a movement through and around their friendship, was more energizing than I had anticipated. If that’s not a legacy worth celebrating, I don’t know what is.

Pretty Little Liars is available for streaming exclusively on HBO Max.