One of the most tragic facts about cinema is that John Carpenter is only being recognized as one of horror’s greatest directors decades after he should have been. While his title as the master of horror is now undisputed, there was a time when his films were largely derided by critics, only being re-evaluated following successful runs on home video and the midnight circuit. The Thing is the most infamous example, a film that is now considered a landmark of the genre but was initially met with a level of vitriol that is almost unimaginable (with terms like “instant junk” and the “quintessential moron movie” being thrown around like confetti). Quite why the film received such a backlash remains unclear (competition from E.T. and Blade Runner that both released in the same window being two reasons), but its subsequent acclaim has led to most of its early critics falling mysteriously silent. Unfortunately, the same cannot be said for another of his films based around the inscrutable world of cosmic horror, one that explores many of the same concepts as The Thing while pushing them in new and (whisper it) better directions — none other than his 1987 supernatural masterpiece, Prince of Darkness.

Although unrelated to its predecessor in terms of plot, Carpenter considers Prince of Darkness to be the second entry in his self-dubbed Apocalypse Trilogy, a series that would end with 1994’s cult classic In the Mouth of Madness. All three draw heavily from the works of H. P. Lovecraft, and see their unfortunate casts of characters being confronted by beings beyond our comprehension, forcing an examination into humanity’s place in a vast and uncaring universe. They also take place primarily in a single location, creating a microcosm of terror that will destroy the world should it escape. It’s a brilliant premise, but judging by reviews both past and present, Prince of Darkness failed to reach the highs of its companions. It’s widely considered the weakest film in the trilogy, and often ranks toward the bottom of Carpenter’s filmography. To some extent this is understandable — it doesn’t have the strong characters of The Thing or the creativity of In the Mouth of Madness, but what Prince of Darkness does have is a feeling of sheer, unrelenting dread. This is a film dripping with atmosphere, with the shadow of impending doom lingering over every second like the grim reaper hiding just out of frame. It manages to make The Thing look tame, and that’s not something just any film can accomplish. The Apocalypse Trilogy has never been more accurately named than here.

More Apocalyptic Than Any Other Apocalypse Trilogy Film

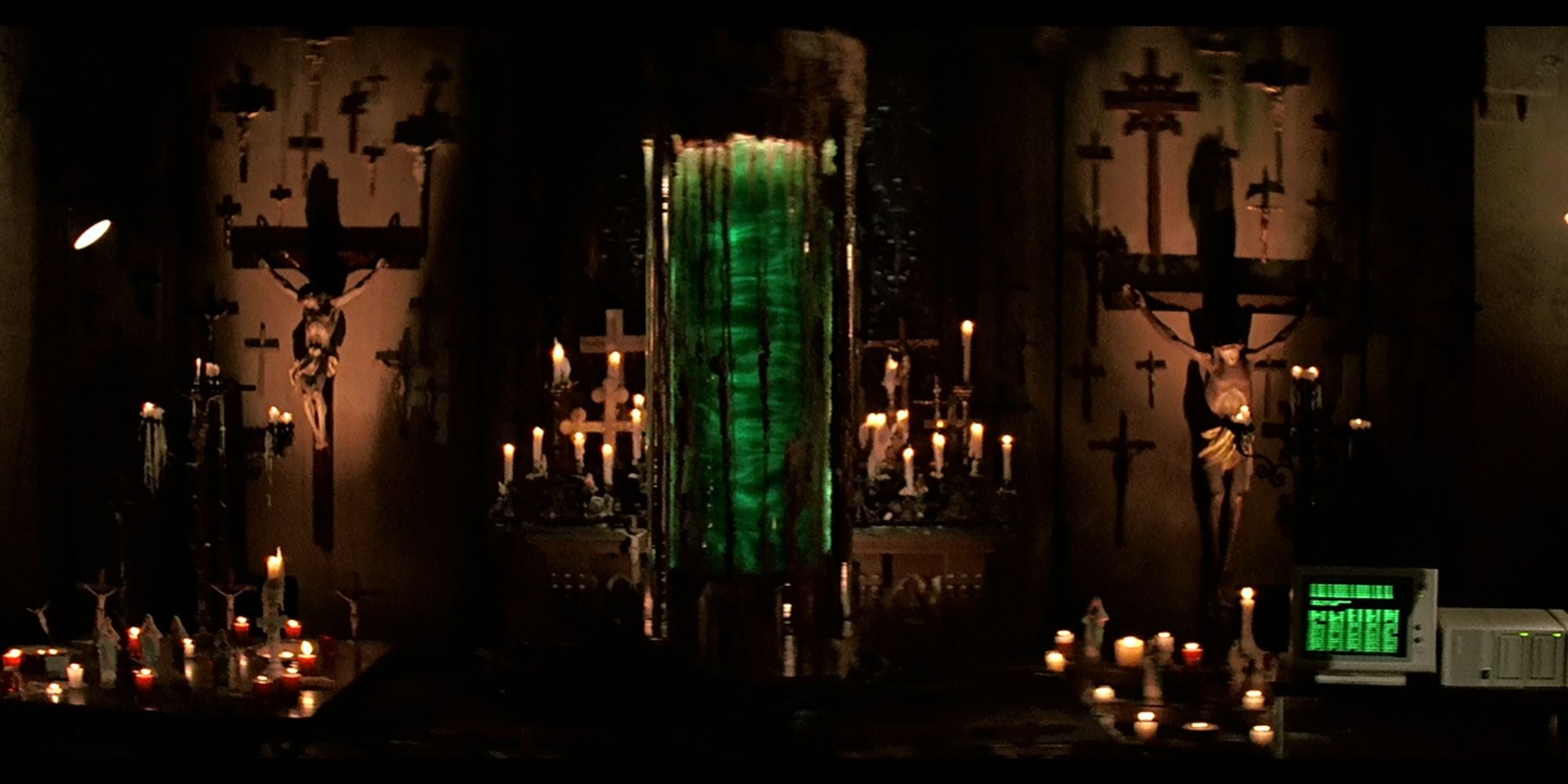

The plot of Prince of Darkness centers around a Los Angeles monastery owned by the mysterious Brotherhood of Sleep, an ancient sect that communicates through dreams. The head priest has died in mysterious circumstances, and his replacement (an unnamed priest played by the always watchable Donald Pleasence) invites physicist Howard Birack (Victor Wong) and a small group of his students to join him in the monastery. The priest hopes they will be able to provide answers to the strange cylinder of green liquid that he has found in the basement. Investigations reveal it to be the corporeal embodiment of Satan, and soon after it begins possessing members of the group after it begins to escape from its confinement.

Unable to leave due to a mass of schizophrenic homeless people surrounding the building, the survivors are forced to combat this evil before it succeeds in bringing the even more nefarious Anti-God into our world, all the while battling a recurring dream of a shadowy figure emerging from the church that appears to be predicting the future. Just reciting the plot can make it sound a tad silly, but Carpenter treats it with maturity to elevate it above its B-movie roots. The result is an engaging story that dares to ask grand questions about human nature and our importance (or lack thereof) in the universe, echoing themes explored in The Thing while still retaining a distinct identity.

Building a Sense of Dread

As previously mentioned, Prince of Darkness is at its best when it’s sowing the seeds of inevitable doom, and thankfully Carpenter realizes that too. Characterization is serviceable but cliché, with only the most threadbare of development given, so we’re invested enough for our leads to make it out alive. This might sound like a problem, but in a film where petty human drama like love triangles become meaningless when faced with our extinction by a creature we cannot begin to understand, it’s only fitting that complex character arcs fall by the wayside. The trade-off is more time spent immersing ourselves in Carpenter’s latest ordeal, and he wastes no time pilling on the tension. The opening montage is some of his strongest work as a director, with innocent scenes of college life juxtaposed against the priest’s initial realization that the world is in great danger, all sandwiched between an ominous lunar eclipse above and an onslaught of ants below. The score is the final touch of horrific delight — a foreboding growl based around three notes that drips blood from every tone, giving a sinister undertone to mundane scenes like two students walking through an idyllic campus. Even after the credits have rolled Carpenter rarely allows for silence, instead keeping the soundtrack pulsing away to ensure the film has a constant sense of energy. It’s among the finest scores of his career, and serves as the perfect fanfare for the incoming Armageddon.

It's a hard job to construct a tense and well-paced build-up without slipping into plain old boredom (while still remembering to have an actual payoff at some point), but Carpenter’s economic filmmaking is at its peak here. The pace is quick but never rushed, allowing for a continuous stream of movement that never lets you get attached to one person or location. Characters float between rooms while discussing theological questions, barely registering the torrent of worms gushing down the windows that soon feel comparatively tame as we descend further into this nightmare. Some of Carpenter’s most striking shots are on display, from the menacing group of homeless people silently watching the church, ready to pounce like an attack dog at the first sign of escape, to the heart-stopping image of a dead man’s skin being resurrected by hundreds of writhing beetles before crumbling to pieces and vanishing into the night. The highlight is the distorted dream sequence. Its low-fi appearance that conjures memories of a VHS is an interesting choice, but it gives it an otherworldly tone that adds to its mystique. It’s a haunting image, both literally and figuratively, and its role as a metaphorical ticking clock counting down to a hellish future is the film’s most terrifying creation.

A Creepy Atmosphere Adds to the Horror

The monastery itself is an excellent location, and Carpenter’s masterful sense of space exploits its every crevice. His trademark widescreen cinematography remains some of the most quietly effective in the industry, transforming mundane scenes into works of true beauty (look how he frames the priest’s arrival at the church, its vast exterior staring down at him like he’s not even worthy of standing in its shadow). The interplay between the old and the new is fantastic, with ancient crypts lit only by candles becoming the resting place for advanced scientific equipment rendered useless in the face of such an unknowable force. Before long the survivors are constructing barricades out of sofas and using planks of wood as weapons, a return to a primordial way of life that’s only fitting given the enemy they face.

It’s this mindset that defeats the Anti-God, with the mirror it's using to enter our world being shattered not by computers or degrees but instead by a simple ax. As with all good Lovecraftian stories, victory feels more like defeat. The Anti-God is still out there, and the actions of today have only bought them a few years before this all happens again. The Thing ended on a downer, but at least there was the sense that a potential global catastrophe has been averted. With Prince of Darkness, there’s little to suggest they’ve even made a dent… especially if that still-persisting dream is anything to go by.

A Simple Moment of Greatness

Prince of Darkness’s greatest moment is also its simplest. Following a night of mayhem that claims the lives of most of the team, the dawn rises on a planet that may have just hours left. The chaos of possessed zombies and a liquid Satan gives way to a moment of peace, and Carpenter uses this time to cut to an exterior shot of the monastery. A car drives past. Its driver pays no attention to the building as if it’s the most ordinary thing in the world, then we cut back inside and the story continues. It lasts for a matter of seconds, but the implication is terrifying. Humanity is on the verge of annihilation, but only the tragic souls trapped inside that building even know it’s happening. That driver came within a stone’s throw of certain death, but instead they just drove past in blissful ignorance, a chilling thought that speaks to how little we really know about the world around us.

It’s a theme that reverberates throughout the film, evoking the old Lovecraft idea of humans being nothing more than a speck of dust on a giant rock who understand nothing about the universe around us. For centuries we believed the Devil was the ultimate personification of evil, and now we learn that he’s merely a foot soldier for a far greater entity. It’s a revelation that fractures both the world of science and religion, and as the credits roll we’re left wondering what other truths are mere fabrication. Prince of Darkness is not perfect, and acts as a better showcase for John Carpenter the director than John Carpenter the writer — our supposedly rational characters are very quick to accept the supernatural, for example — but when directing is this good it’s not worth concerning yourself with such matters.

Nothing in his filmography has a better atmosphere than this, with the dread that persists and torments from the first frame to the last creating a disturbing experience rivaled by little else. The best horror is the kind that lingers, and when Prince of Darkness smashes to black following its eerie final minute, you’ll be in no doubt why Carpenter is horror’s greatest master. The apocalypse is coming, evil lurks behind every corner, and there’s nothing we can do to stop it… what’s not to love?