Horror has always been queer. And queer people have always resonated with horror stories. The issue is that queer people or queer-coded characters have usually been relegated to the role of villain. This all began when Hollywood executives decided to take a more controlling role regarding censorship in film and in 1934 instituted the Hays Code– a set of rules that included the clause that anyone embodying queerness, or any other “amoral” liberated behavior, needed to be punished in the stories they were present in. This set off a chain reaction that became a trope. But that didn’t stop queer people from seeing themselves reflected in many of the iconic films that followed. Stephen King and Brian DePalma’s Carrie can be read as a queer character coming-of-age in a religiously oppressive home. Tobe Hooper’s Leatherface (Gunnar Hansen) of Texas Chainsaw Massacre and Alfred Hitchcock’s Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) of Psycho could be considered precursors to that controversial Silence of the Lambs figure Buffalo Bill (Ted Levine). In recent years, however, the tables have started to turn and queer people have started to represent themselves in media, and not only as the villain. Horror is changing. Films like Diablo Cody and Karyn Kusama’s Jennifer’s Body, the Fear Street series on Netflix, and recent release and folk horror darling The Last Thing Mary Saw are queer-centered horror. They aren’t always joyful, the queer characters aren’t always the heroes, but they are honest stories demonstrating the full spectrum of the queer experience. And we’re here for it.

The most homophobic Tennant of the code stated that anyone who was acting “immorally” was required to be shown facing consequences for those actions. Every movie that demonstrated freedom had to become a morality tale. This is where the trope of queer people being villainized was born. Tropes become tropes through repetition, and this one was repeated a lot. In fact, the queer coding of villains trickled all the way down to Disney–look at Ursula the sea witch, who was inspired by drag queen Divine, or Jafar or Scar, fabulous men with “feminine” mannerisms and flamboyant style. Anyone who defied the gender binary in any way was automatically “bad.” The long crawl back to positive representation has not been easy. In the ’90s and 2000s there were more queer stories being told, but they usually fell into one of two categories; comedic stereotype, often with gay characters played by straight actors, or trauma porn.

Horror has always been subversive and therefore appeals to people who are relegated to the fringes of “normal” society. Whether intentional or not, the genre of horror has been adopted as a kind of queer subculture, with many queer people seeing themselves in even the villains in these stories. One very early example of queer-coding in horror occurred in James Wale’s The Bride of Frankenstein. Director James Whale was openly gay throughout his career, The Bride played by Elsa Lanchester has inspired many-a drag looks for nearly a century. Ernest Thesiger as Dr. Pretorious has become a beloved queer character, despite meeting an untimely demise in the film thanks to the Hays code. Unfortunately, things got real regressive after this film and queer coding had to be more subtle. Brian DePalma’s Carrie can be easily interpreted through a clear lens. Sissy Spacek's Carrie is timid, weird, othered, tormented, and traumatized both by her bullies at school and by her overbearing and very religious mother played by Piper Laurie. Many queer people who grew up in religious households and small towns deeply resonate with Carrie’s journey of marginalization and liberation, even if the whole high school does end up paying the price.

Silence of the Lambs, Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Psycho, and the cult-classic Sleepaway Camp take on gender-nonconformity in their villains, which has been critiqued and criticized and dissected and is more transphobia than representation. But that hasn’t stopped gender-conforming horror fans from relating to these characters. Buffalo Bill is a character whose murderous impulses are driven by his psychopathy and his desire to be a woman–the psychologist who analyzes James Gump does clarify that he isn’t trans he just… wants to be?? Anyway, that’s why he traps women, skins them, and wears their skin. Leatherface is a chainsaw-wielding cannibal who assumes the role of matriarch for his murderous and terrifying family. The character wears makeup on his skin mask, a wig, and an apron during the infamous dinner scene. He “cooks” their meals, he does the domestic chores, he is seen-not-heard and takes on a subordinate role to his father–the patriarch of the family who leaves the home to work. Norman Bates in Psycho is another gender-confused murderous villain, though his reasons are slightly different. His deceased mother, who was overly critical and overbearing throughout his life lives in his head rent-free, becoming a sort of alternate personality for him; terrorizing him and pushing him to commit acts of violence on women he finds himself sexually attracted to. Sleepaway Camp is potentially the most egregious of these offensive twists, because in the last few minutes when it’s revealed that the main character Angela (Felissa Rose) was raised as a girl but is really a boy, and thus becomes a serial summer camp murderer. This is revealed by Angela flashing her genitalia and giving one of the most terrifying facial expressions in horror history. Yikes.

Queer people have gotten used to accepting breadcrumbs. There are whole subreddits, forums, academic conference panels, and YouTube essays dedicated to the topic of queer horror, so it became obvious that it was past time for respectful and honest representation of queer people in horror. Rocky Horror Picture Show in the 70s joyful and Technicolor exploration of gender, sexuality, and Tim Curry in that corset and heels became the cult classic that wouldn’t quit. Clive Barker and Hellraiser in the 80s explored themes of BDSM and the co-occurrence of pleasure and pain inspired by the author’s time in kink clubs in the 80s–where anxiety over the AIDS crisis lead to other ways of exploring intimacy and a whole new era of art, fashion, self-expression, and sex. The ’90s brought films like Interview with a Vampire and Heavenly Creatures, but queer horror didn’t really start to come into its own until the new millennium.

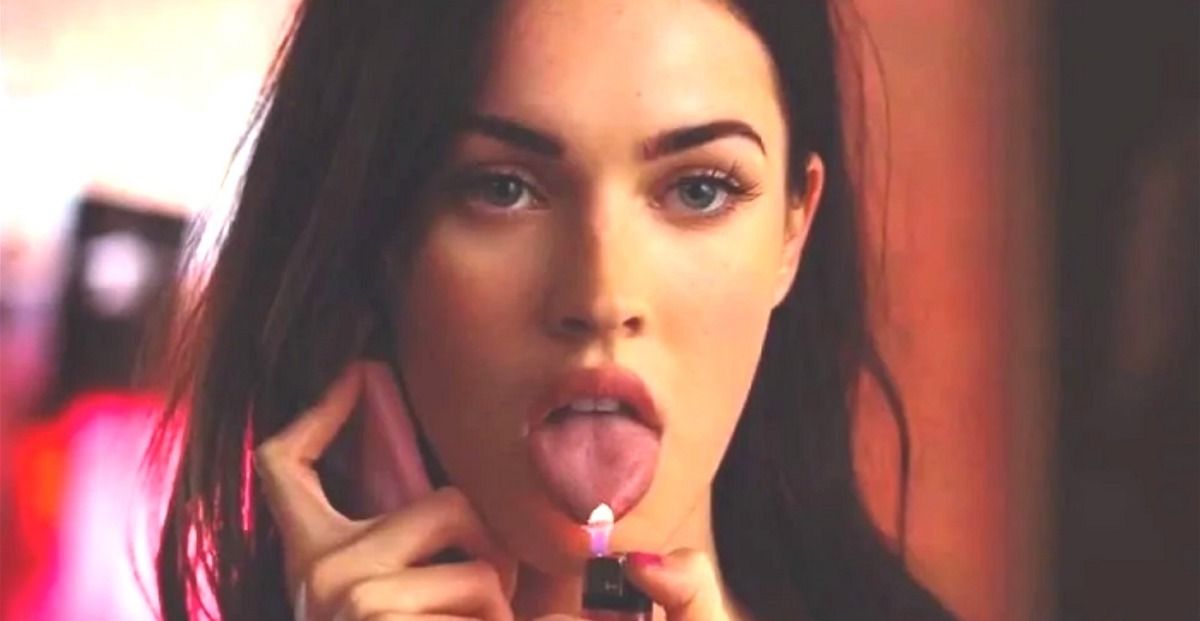

High Tension, Let the Right One In, and Jennifer’s Body felt louder, proud, and out than many of their horror predecessors, while also being serious works of art. The stories were more full-bodied and nuanced, the characters were handled with care, and they didn’t feel the need to hide the queerness behind symbolism, or make the queer characters outright evil as a rule. Jennifer’s Body has become a cult classic in recent years, but when it first came out, people didn’t like it. Both Diablo Cody and Meagan Fox have said in interviews that this was due in large part to studio sexism, which refused to market the film to anyone but teenage boys simply because Fox was in it. This movie wasn’t made for teenage boys, though. It was made for horror-loving queer-or-questioning femmes. Meagan’s open bisexuality lent an air of authenticity and representation to the film that honestly isn’t even a sure-thing in today’s films–never mind 13 years ago. The film follows best friends Jennifer and Needy as they come of age and grapple with the surprising intensity of their connection. Jennifer is sexually assaulted and sacrificed after a concert one night by a band performing a demonic ritual for fame and fortune, but non-virginal Jennifer comes back as a lot more than they bargained for–the monstrous feminine. Jennifer’s Body is part coming-of-age, part revenge story, part feminist commentary, and part queer love story. Many queer women experience the kind of intense friendship that Needy and Jennifer have when they’re young and closeted. Sometimes these friendships fall apart when one friend comes out as queer and the straight (or still closeted friend) comes down with a case of queerphobia and begins to see their former friend as something threatening, something innately other. Part of why this film has received so much retrospective acclaim is that it was a bit ahead of its time. Queer stories like this weren’t being told yet. The early 2000s queering of horror definitely paved the way for what is becoming a queer horror revolution.

The Fear Street trilogy that was released on Netflix in 2021 tackled queer representation unapologetically, gave a killer story, horror fan service, excitement, and three distinct subgenres of horror in one perfect package– a supernatural 90s slasher, a 70s summer camp slasher, and finally the burgeoning new trend of the genre, folk horror. Fear Street Part One and Part Three center a queer love story, forbidden through the ages. In 1994 Deena (Keanna Madeira) is going through a break-up with her first love Sam (Olivia Scott Welch). Sam recently moved to Sunnyvale, leaving Shady Side behind and Deena with it. There is some (at times heavy-handed) class consciousness stuff going on, which does tie into the overarching plot of the trilogy, but aside from Deena being from the wrong side of the tracks, the couple faces the little issue of Sam’s inability to come out. That storyline has been done to death but because Fear Street takes place in high school, it’s realistic. The love between the two girls isn’t fetishized or shot through the male gaze, and it also isn’t treated as any less valid than the other relationships in the films–in fact, it is the foundation for the whole trilogy. Back in 1666, we see the same two actors playing two women in love while living in the Union colonial settlement, which will eventually become Shady Side and Sunnyvale. The separation of the two women and the demonization of Sarah Frier (Keanna Madeira, who also plays Deena in 1995) (think, Salem Witch Trials) result in the curse that plagues the town with horror and bloodshed that traumatizes Shady Side in 1978 and again 1994. The moral of this story is for the homophobes out there–Gay Rights or Get Cursed.

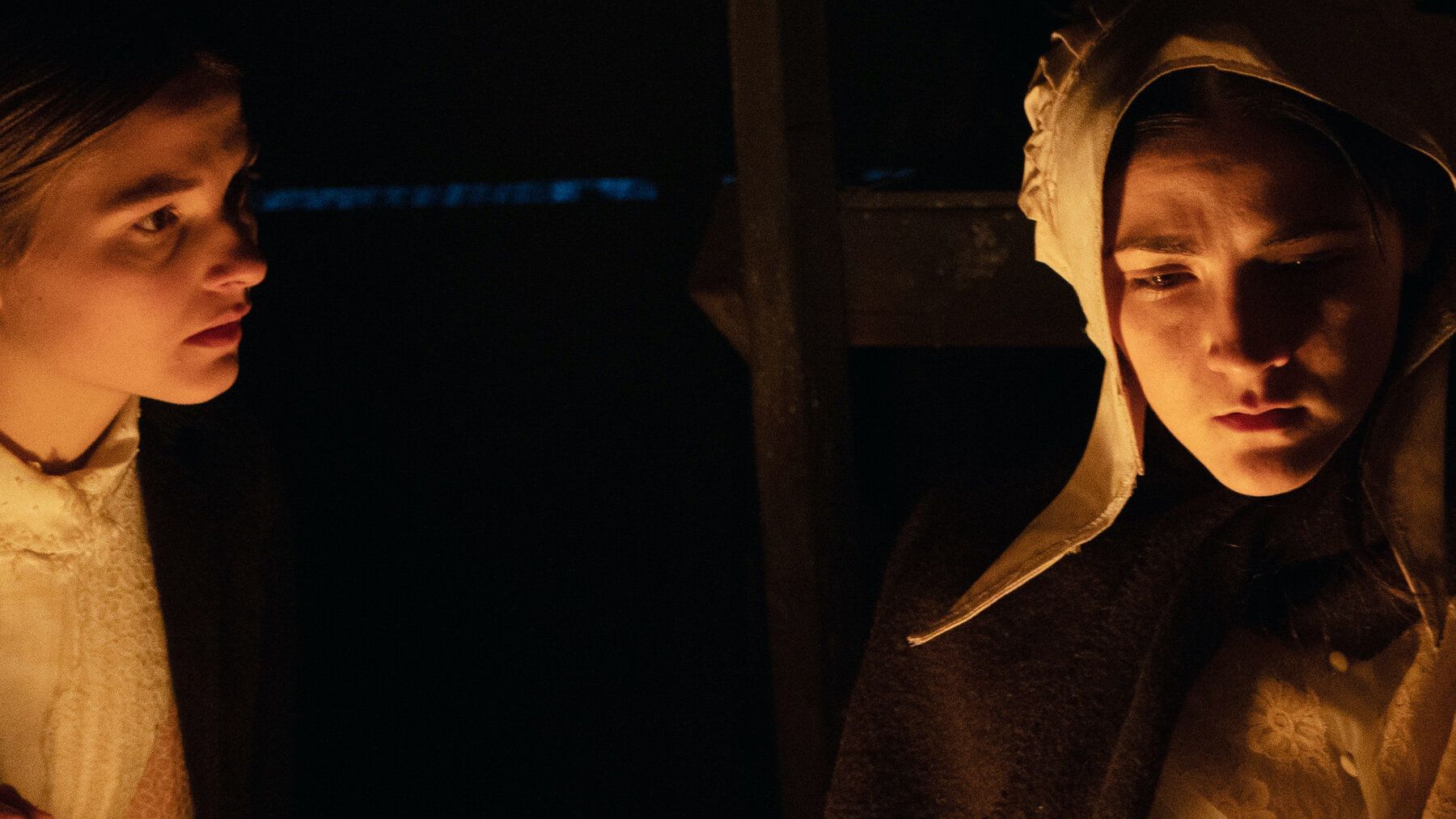

The Last Thing Mary Saw just dropped on the Shudder Streaming service and tells the tragic love story of Mary (Stefanie Scott) and Eleanor (Isabelle Fuhrman). Mary lives with her family in an early colonial settlement on Long Island, New York, and Eleanor is the family’s maid. From the start, the two young women and their love affair prove to be a source of fear and shame for the family. The Puritanical Christian family punishes the girls for their indiscretion by having them kneel on rice and recite scripture. No matter what torture the girls endure, however, they don’t stop loving or seeking out the intimate company of one another. While there is another level of supernatural horror in The Last Thing Mary Saw, the depiction of queerness in a time when many would have the world believe it didn’t exist, and the honest and painful portrait of the incidence of religious trauma in queer people are powerful, to say the least. This film doesn’t by any means have a happy ending, but in the kind of religious household where moral superiority excuses extreme abuse, the liberation of Mary and Eleanor through their love for one another–and how they are in many ways the flawed heroes of this film–sets the tone for the new queer age of horror. It’s about time.