Beasts of the Southern Wild is a spellbinding adventure set just past the known edges of the American Bayou, in a forgotten but defiant community known as The Bathtub. The film follows a girl named Hushpuppy (Quvenzhané Wallis) as she takes on rising waters, a sinking village, changing times, an army of prehistoric creatures and an unraveling universe that she bravely tries to stitch back together through the sheer force of spirit and resilience in order to save her ailing father, Wink (Dwight Henry). Shot on location in the coastal parishes of Louisiana with local non-actors in the lead roles, Beasts of the Southern Wild came to the Sundance Film Festival a hand-made, fiercely imaginative underdog and left a runaway hit and winner of the coveted Grand Jury Prize.

At the press day, we sat down with Wallis, Henry and director Benh Zeitlin to talk about what inspired the heartfelt story about a fantastical bayou neverland and its tenacious characters. Wallis and Henry discussed what it was like acting in their first movie, how they prepared for their roles, and the special bond they formed on and off screen. Zeitlin told us about the collaborative writing process, how he set about creating a mystical Mississippi Delta community, and why he has always been interested in people that never abandon the places and people they care about even when it’s dangerous.

Question: Can you talk about casting non-actors in the lead roles and what that process was like?

Benh Zeitlin: It’s casting people who are acting for the first time more than it is non-actors. I mean, these guys definitely aren’t playing themselves in any way. They really learned how to play these parts and then they have this inborn charisma that you need to light up the screen. It’s a different kind of process and it really benefits us. We try to collaborate intensely on every element of the film, the characters included. What ends up on screen is very much [collaborative]. There are things that I wrote. There are things that Dwight (Henry) told me how he would do it. We would bring the script to the bakery at night and we would do these interviews where we would go through our lives and take our lives and relate them to scenes in the script, then rewrite scenes based on that. I would say “Here’s what I have Wink doing in this scene. I feel like this connects to this experience that you’ve had.†And then, he would say “Well I wasn’t really thinking that way at this time. My focus was here.†And so then, you would throw that script right into the donut oven and burn it and rewrite it and always try to get the script as close as possible to the voice of the characters and let the people who are playing the parts teach us about what it would have been to go through some of the things that happened in the film.

Dwight, before you acted in this film, was your other job at a bakery?

Dwight Henry: I own a bakery called the Buttermilk Drop Bakery and Café. It was actually right across the street from where they used to do the auditions. They used to come over and get breakfast in the morning and get donuts in the morning and put little flyers in the bakery if anybody wanted to audition for a part.

What’s your specialty?

Henry: Buttermilk drops, hashbrowns, stuffed bell peppers and a whole array of different types of donuts and pastries and candied yams. They used to come over for my sweet potatoes every day. They’d come over and it was just sweet potatoes, sweet potatoes, sweet potatoes. I specialize in a number of things.

Did Benh ask you to be in the movie or did you get involved when you saw all this activity going on?

Henry: Well, that’s another little story right there. I put the flyers in actually for my customers to get it, and I always wanted to go over there and audition for it, but I never had time to go over there running a restaurant. One day, me and one of the producers were sitting in the bakery. So I said “C’mon Michael (Gottwald), let’s go over there and do this audition. I got a little time right now.†So I went over there and did the audition and about two weeks later he said “Mr. Henry, Mr. Zeitlin wants you to do another read.†So I said “Another read?†I said “Okay, it’s getting serious now. I’ve got to go back again.†I went back and did the other reading, and within that time period of me doing the second reading, I moved my business from one location to another location, and they were actually looking for me to give me the part but no one knew where I was at. They were asking all my neighbors and my old landlord, “Where is Mr. Henry?†Nobody knew where Mr. Henry was at until two days after I opened up. Mr. Gottwald come in and said “Mr. Henry, you got the part.†He had a calendar in his hand and a schedule. I needed to move and I couldn’t do it right then and there. I wanted to do it. I was flattered but I had some things I had to work out first. So, it took a little while for me to work things out. They gave me a chance to work things out, and I worked things out and went and did the film, and it’s been wonderful ever since.

Zeitlin: He turned the part down probably three times.

Henry: I had to turn them down three times. I wanted to do it, but had to turn him down because I was running a bakery and building something up for my children, and I wouldn’t under no circumstances sacrifice something that I worked so hard to pass onto my kids for an acting career. That would have been selfish of myself. So, I had to work things out and I worked things out. They seen some things in me that I didn’t see in myself and believed in me, and I worked it out and I was able to move and do the film, and they made a lot of concessions for me as far as giving me a driver to bring me back and forth to the bakery. Whenever I needed to come back, I came back. We made concessions with each other and it worked out for both parties.

Can you talk about your character’s relationship with Hushpuppy? How did you handle those really tough scenes and what were the two of you like when the camera stopped rolling?

Henry: We explained to her that a lot of times it may seem like I was being tough on her, but I was actually trying to emphasize the importance for her to know these things because her dad is dying in the movie. We told her that I’m not really yelling at her. I’m just passionately trying to emphasize the importance for her to know how to do these things because her dad is not going to be here that long and she doesn’t have her mother, so she has to know how to do these things. I have a daughter her age that’s seven years old so it was easy for me to relate and know how to interact with a seven-year-old girl. It’s the same thing as I did with my daughter. I brought some of the same fatherly skills on screen. We did a lot of things in between shooting. Me and Nazie (Quvenzhané’s nickname) would go to the side and we’d play different games. There were a couple different instances when we weren’t shooting. We’d go in the kitchen, me and Nazie, and we’d bake cookies together like a father and daughter do. We’d cook together and we’d eat together, so we did some things to draw a bond between us while we were on camera and off camera.

Wink is doing what he feels is right even though it seems like he’s putting his child in danger during the story. How did you deal with that?

Henry: Well it’s a dangerous region that we live in. You’ve got to understand the region we live in. Living on the Gulf Coast, we often have to go through dangerous situations, whether you’re a child, an adult or a senior citizen. You have to endure the same thing living on the Gulf Coast, the possibility of losing your family, losing your home, losing your loved ones, being displaced and things like that. So, she has to know how to do these things because you have to understand her daddy’s not going to be there that much longer. She doesn’t have her mother so I was constantly trying to emphasize the importance and the urgency for her to know how to do these things, feed herself, take care of herself because daddy’s not going to be here that long. I was always emphasizing with an urgency that she needed to know how to learn these things very fast.

What was the experience like for you to act in a feature film for the first time?

Henry: It was a tremendous experience and the best thing that came from it was when everybody first saw the film at Sundance and stood up and clapped. They enjoyed the film and stood up and applauded, 1500 people. That was the best feeling in the world, that people enjoyed the work that we did.

While you were making the film, what was it like?

Henry: We had a lot of direction. We had some professional acting coaches from New York to work with me in the bakery in the middle of the night. I was baking donuts and we were working on different acting techniques and reading scripts. Before we started shooting, we went over every scene. Benh crafted the script just like he said. We’d go over the script and he’d throw away the script after we read it. Then he asked me how I would say this and do this in my own words versus doing it in his words. That made it seem more natural and real for me instead of doing it in his way. He wanted me to say things and do things in the way that I would do it, not in the way he would do it. That made it much easier for a first time actor to know how to do these things because I’m not trying to do something that someone else is telling me to do. I’m actually following my own directions because I basically wrote the script myself. He threw his words out and put my words in so that’s basically my movie. (laughs)

Zeitlin: All of Dwight’s scripts are glazed with sprinkles. If you look at all those pages, it’s like the donut shop is all up in those.

Henry: Thank you.

Quvenzhané, what was it like working on your first movie?

Quvenzhané Wallis: It was fun because I wasn’t expecting all this commotion and dirtiness and stuff like that. I’m not that kind of person. I’m just relaxed and don’t move and I’m clean.

Zeitlin: We had to go through dirt training for sure.

Wallis: They actually had me jumping in mud.

Do you still want to be an actress when you grow up?

Wallis: Maybe.

It depends on how much mud you have to deal with?

Wallis: Yes.

Now that both of you have done one film, is this something you’d like to pursue more of in the future?

Wallis: Yes.

Henry: I’m going to ride the wave wherever it takes me. If it takes me in that direction, I’ll go. But one thing I know for sure, I’m not the Hollywood type. I’m not ready to pack my bags and leave the town and my business that I love and my kids that I love more than anything and pack them up and come to Hollywood. I love California. I love Hollywood. But I’m not ready to uproot what I believe in to come to Hollywood. Hollywood would have to come to me before I’d go to Hollywood.

Quvenzhené, is Hushpuppy someone you can identify with or that’s close to you personally? Did you model her after someone you know?

Wallis: She’s close to me because we just get along very well.

Zeitlin: One thing I saw in Quvenzhané when she first came in, and it was so important to the character, and it’s something in Dwight’s character too, is these guys are so confident and fearless in life. There’s nothing you can do that scares her or freaks her out. It’s the same thing with Dwight. There’s that one quality. The way that he’s raising her is not to be afraid. He’s going to let her fall down and he’s going to let her pick herself back up and he’s going to teach her fearlessness because he knows that’s what she’s going to need to survive. Even in her first audition when she was five years old and walked in, she was not afraid of me. When I was telling her something in the audition that she did not want to do, she told me “That’s not right. You’re not supposed to throw things at people.†She was really defiant, and defiant in this sweet way, and that was what I saw in her natural person that really connected to the character. Quvenzhané is not anything like Hushpuppy in the day to day of what she does, but there’s something about how she is really wise beyond her years and fearless and strong in this way. When I saw that, I knew that was the character and who she was going to be.

Page 2

Can you talk about the challenges of shooting on location and how you went about creating the look and the vibe of The Bathtub?

Zeitlin: We tried to build everything actually as opposed to building facades or fake things. Even though it may have been easier to build sets with flyaway walls or anything like that, we wanted to be able to shoot the film and allow these guys to operate on the sets as if they were real. Wink’s shacko, where they go through the storm, was a real house that my sister built. It’s all from materials that she found in the woods in that location and she actually lived in that house while she was building it throughout production, and so all those animals are her animals. It wasn’t like we had to fake it. It actually existed in the place. It wasn’t like we had to hit marks and avoid things. It felt lived in and you could shoot almost like it was a documentary. We tried to take that to every set and every big set piece. We wanted to actually experience what it felt like and let that find its way into the performances and the fabric of the film.

What about the floating palace that’s out in the middle of the water that advertises “Girls, Girls, Girls� Is that a real location?

Zeitlin: Well the sign we put on. A lot of the art direction in the film was finding these crazy, bizarre places, and that was this boat that’s sitting on the north shore that this guy got into a real estate dispute over the ownership of the land, and to get revenge, he sank that boat out on the property to claim it and it’s been sitting there for twenty, thirty years. That’s actually there, and then I took the idea for the place from these riverboats that existed in New Orleans in the 20s and 30s, these kind of floating places where they’d have gambling and boxing matches. I thought about where Hushpuppy might imagine that her mother had gone to. Wink probably didn’t tell her the whole story. He probably just said “Your mother’s gone away; she swam away,†and not give her any more information. And then, I tried to build the place based on the mythology that Hushpuppy would have created around where her mother might be.

In the middle of this very real environment that you created, you also threw in some fantastical elements with the Aurochs. How did you approach CG versus practical and decide what they should look like to fit in with the rest of what you’d created?

Zeitlin: We wanted everything in the movie to be organic and that very much comes from the place. I mean, the Bathtub doesn’t have after effects in it. There’s no technology. There’s no computers. We wanted everything to feel organic and alive. And so, not even knowing how we were going to execute it, we decided very early on that the Aurochs had to be real animals, that we had to figure out a way to train animals and work with animals to get them to play these parts. I don’t think of them as imaginary. I think of it as the film is Hushpuppy’s film and for her everything is real. But they needed to emerge from her and so Hushpuppy’s world is built of these organic things. We wanted the effects to be organic and so 80 percent of them are all in camera. We would add things and remove things digitally, but the heart of the effect is reading 1980s practical effects magazines and trying to imitate some of the ways that people used to do things back before we could create them out of digital.

To what extent do you consider this to be a fairytale story not set in the real world?

Zeitlin: I don’t. For me, it’s a very real story. I try to think back to the way I experienced the world when I was six. It’s set at a moment before you start parsing out what’s imaginary and what’s real. I remember having an imaginary friend when I was six years old that was absolutely sitting in that chair right there and no one could tell me that he wasn’t there. I wanted to make a film that didn’t condescend towards that and say no, they’re just a kid. They’re just seeing things. I actually took it seriously and respected that point of view, because to me, she is the wise woman of the film and she’s the one who has both the strength and the sweetness to preserve this culture inside of herself. It’s because of her and the unique way that she sees the world. Although you could look objectively as an adult and say she’s imagining certain things and she doesn’t understand everything, the film is her film and we wanted to let her point of view and her reality speak for itself.

You never say Katrina in the film but that comes to mind when you watch it. The Bathtub that’s set in the southern bayou seems like it may as well be another part of the world. Is that part of the sense you have too from spending time there?

Zeitlin: Yeah, definitely. The Bathtub is definitely not a real place. It’s not like we just found a place that was like that and photographed it. It’s definitely a synthesis of a lot of different elements of South Louisiana culture that are all geographically disparate. There’s New Orleans culture in there. Cajun culture is in there. Creole culture is in there. And it’s all being consolidated and concentrated in this little island that we call the Bathtub. That was sort of the idea to build a heightened world out of very real parts and to try to tell this story as a fable. It certainly is inspired by a lot of real things that have happened, and the reason to stay away from mentioning Katrina or anything specific is that we get caught up on that event because it was on TV so much, but it’s really a continuing thing. I wrote the film in 2008 after Gustav and Ike had happened, in this moment that felt like storms have aways come and they’re coming more and more frequently. I wanted to tell a story about moving on into the future and living in a place where every summer the possibility of getting wiped off the map always exists and what it’s like to stand strong there and stand by the place and refuse to leave and fight for it. I don’t want to get bogged down in the politics of George Bush and Nagan (former New Orleans mayor Ray Nagan) and drill now and don’t drill now. To me, that all seemed superficial in the face of something. Down in the bayou, down at the bottom in the marsh, on this island called Isle de Jean Charles where we shot, somebody said to me “I hope that I can live my life on this island and die on this island, but I know that my children are going to be telling their children that once upon a time there was an island called the Isle de Jean Charles and that it doesn’t exist anymore and that culture is not here anymore.†That emotion, to me, transcends all the politics and it’s something that I feel can be universal. That if anybody thinks of a place where they were born and come from and imagines that it’s no longer on the map that there’s an emotion there that can cross the oceans and go anywhere and people can feel what it feels like to have your home threatened into the future.

Quvenzhané, how would you describe this film and what it’s about?

Wallis: It’s about a little girl who lives in The Bathtub with her father and she thinks her father is kidding about how he’s dying because that’s what they mostly do, and she just realized how he was dying even more and she thought it was serious so she started thinking about how she should take care of her father.

You get to do some really cool stuff in the film like running around with firecrackers and sparklers and lighting the stove on fire with a can of hairspray. Was that fun for you?

Wallis: Yes, but that can of hairspray, I have no idea if that was real.

Benh, what did you do to monitor her safety when she was doing these things?

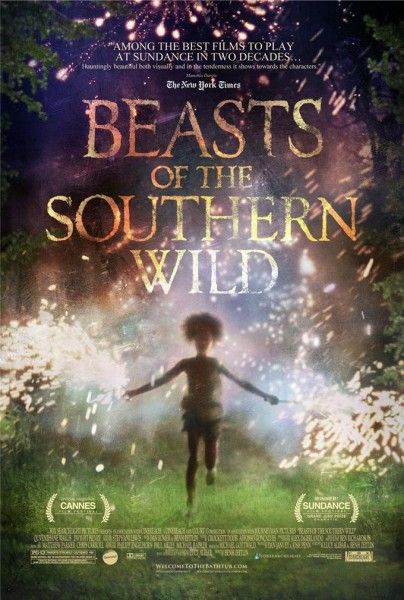

Zeitlin: We made a real effort to make it look like she was in danger. Whenever there were pyrotechnics on set, we had pyrotechnics people and safety people and fire trucks. No one’s life was ever in danger while making the film, but we got to play with some fun toys. I’m going to tell a story about Lynn (Colugia??). When we were doing the fireworks scene, that shot that’s on the film poster, when we were about to do that, our producer went up and talked to her and said “We’re going to have these live sparklers and they’re non-flammable. They’re not hot. We just want to make sure it’s okay for her to do this.†And she said “Oh, she’s gonna do it. She’s got to step up and be a woman and do this.†It was always a challenge but always in the spirit of the film – to be fierce and sort of be wild and not be afraid. There was no real reason to be afraid, but we certainly got to push ourselves to do some pretty crazy things.

Do either of you have a favorite scene that you shot?

Wallis: Burp, scream and crawfish. [She lets out a high pitched, piercing scream.]

Zeitlin: That was one of the first things she ever did when she came to work.

Henry: Mine was sitting down and eating all the seafood at the table and I’m looking at her over there eating the seafood wrong and I go over there and tell her to ‘beast it.’ We were really eating that seafood. We ate all that seafood. That was real barrel seafood down there.

Wallis: It was good. Everybody that was under the table came out from under the table because they ate that whole big thing down there.

Zeitlin: The crew was stealing crabs off the table. That was a real feast.

Wallis: That was good too! I wish I was doing that right now.

What kind of animals did you use on the set and were they cooperative when you had to act with them?

Zeitlin: Almost all the animals in the film are me and my sister’s animals. We have a bit of a menagerie in New Orleans. One of the big challenges was touching the pig. That was one of the first things she had to do, that giant pot-bellied pig she puts her hand on. (to Quvenzhané) That was one of the scarier things you had to do, I think.

Wallis: Yes, I actually cried for that one little scene.

Zeitlin: But she managed to do it. It was a big sleeping thing. It was asleep when she did it, but it’s still quite a monster.

What were the Aurochs? Were they cows?

Zeitlin: That is a top secret. I can’t give it away.

How many shooting days did you have?

Zeitlin: I think 52. It was a long shoot. That might include the special effects shoot. There were about seven weeks of principal photography.

Wallis: It was three months, and for all of the movie, it was three years.

Zeitlin: We shot about 2-1/2 years ago at this point. She’s grown up since we’ve been editing.

Wallis: If you want to start from the audition, I’ve gone from five years old to eight. And if you want to start from shooting, I’ve gone from six to eight.

Quvenzhané and Dwight, you both went away for three months to make this movie. Now that it’s finally coming out, are you excited that your friends will finally see what you were doing?

Henry: They know already. Everywhere I go, people are starting to recognize me from different things that we’ve done and people seeing little things, so they’ve got a hint about it already that it’s real and it’s coming. They’re waiting to see it in theaters now and make sure you all tell everybody.

Zeitlin: They recognize me when I go into the bakery now. They know who I am when I go in.

Henry: We are starting to be recognizable.

When did you first realize this film was going to be something very special?

Zeitlin: It was very surreal going to Sundance. We finished sound mixing the movie two days before it screened for the first time. There was no real time to think about what was going to happen or how it was going to go, and even the first time I saw it, I was still mixing sound in my head and thinking I need more magenta in this shot. I couldn’t really experience the movie yet. Some of the early things that were written about it, when I read them, it sort of took me back to 3-1/2 years earlier being on the docks ranting to my friends about what this film could be and what it was going to be like and what it was going to say. Seeing that that had gotten across was kind of a turning point moment where I could manage to step out of making the film and realize that we’d said what we set out to say. I’d probably even forgotten what that was, but hearing it rearticulated was really moving, and you just start to realize that it was in there, that what we were trying to communicate was in the film. That felt really good.

Beasts of the Southern Wild opens in theaters today.