In 1954, Elizabeth II has just been crowned, I Love Lucy has hit the small screen, and the invention of commercial frozen meals fool husbands into believing they can cook. It’s a society where women are a part of the workforce but maintain a desire for marriage. The men are on board with these changes….for the most part. If you enjoy this kind of tension, Alfred Hitchock’s Rear Window is your catnip. On the surface a thriller about voyeurism in both the thematic and academic sense (film theorist Laura Mulvey regularly invokes the film to explain the concept of “The Male Gaze”), there is also no denying its commentary on the New Woman as a source of conflict. This is particularly pertinent for the wheelchair bound L.B Jefferies (James Stewart), who spends the first half of the film being snide towards his girlfriend, Lisa Fremont (Grace Kelly). It’s not until he realizes she is as much of yenta as he is, that it becomes clear there is more to her than expensive dresses and name-dropping: within those $1,100 garments stands a morbid Nancy Drew who opens his eyes to the fact that an interest in Harper's Bazaar can coexist with being a pervert.

To suggest Rear Window is a feminist film, or that Hitchcock was merely a balding Gloria Steinem would be a tough sell. Yet there are glimmers of a hope in both the reversal of traditional roles between Jefferies and Fremont, as well as the insistence that there is more than one type of woman in the world, and that Jefferies’ insistence that marriage is a by-product of nagging is only one of many possibilities.

Grace Kelly as Lisa Fremont

First, let's accept the fact that Jefferies is a bit of an imbecile. “Where does a girl have to go before you’ll notice her?” purrs Grace Kelly, universally accepted as the most beautiful woman in the world. “If she’s pretty enough, she doesn’t have to go anywhere," he replies, presumably suffering from glaucoma as well as the broken leg. Perhaps his vision is skewered by assumptions about the values of his model/socialite girlfriend, who makes an effort to bring him dinner, but not to read the room; upon entering his grubby apartment, Fremont flits around making an exhibition of turning on lamps and commenting on the hectic day she has had: a dash to the Waldorf “for a quick drink with Madame Dufresne”, a lunch with the glitterati of Harper’s Bazaar, followed by cocktails with a Hollywood producer and his socialite wife. Immobile and a far cry from his usual life as an action photographer, it’s little wonder Jefferies is a bit tetchy upon Miss Thing swanning in to regale him with her full diary. But he has found a way to pass the time — using a long-focus camera lens to spy on the neighbors, and enduring visits from his nurse, Stella (Thelma Ritter).

The truth of the matter is that Lisa Fremont is not the frivolous good-time-girl he imagines. Running from one event to the next is all in a day’s work for the woman who, between these glamorous-but-business-related engagements also makes the time to arrange, pay, and tip for her man’s meals. A woman consistently offering opportunities and contacts in a desperate bid to make him happy with life, and with her. Despite these thoughtful displays, Jefferies remains passive and irritable, though it is obvious that he needs her more than she does him. Maybe it is this knowledge that feeds into his resentment. Sure, she’s a cosmopolitan girl with cosmopolitan tastes, and therefore he is quite right to assume she is ill-equipped for his life of eating fish-heads and living out of one suitcase.

But Fremont protests, “I don’t care what you do for a living, I’d just like to be a part of it somehow." Better yet, she can get him lucrative photographic work at the most prestigious magazines, “handsome and successful in a dark blue flannel suit." But he’s just not that kinda guy. After serving a perfect dinner and stoically deflecting his continual underhand jibes, she takes her leave with a sunken heart and assassinated character. Not one to let bad juju remain in the apartment, Jefferies suddenly wonders about keeping things “status quo." Whether his thoughts refer to civilized greetings in the street or a wish to both own and consume his proverbial cake is unclear, but Fremont refuses to play ball. “With no future?”, she inquires one last time. For Jefferies, marriage means “rushin' home to a hot apartment to listen to the automatic laundry and the electric dishwasher and the garbage disposal, the nagging wife," and this simply will not do for our ironically inert man of action. “When am I gonna see you again?” he asks sheepishly after his deluge of snide. Fremont refrains from going full Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, and tearfully explains that it won’t be for a long time…or rather “not until tomorrow night."

However, despite her love being stronger than the desire to wheel Jefferies out the window, Lisa is the film's most active and powerful character. She is independent, knows what she wants, and refuses to entertain Jefferies’ anxiety about women. She exists as proof that they no longer live in a combat boot or Vogue world, and is as capable of getting her hands dirty as she is of spending money. Throughout the film, Fremont embodies a range of roles without ever sacrificing her essence: supersleuth and sex symbol, she is a wily go-getter who scales balconies, remains cool in the face of danger, and is more than happy to rock up uninvited with only a négligée and the announcement that she will be staying the night.

Mercifully, Jefferies begins growing brain cells, and notices his gal possesses the smarts to match the bank balance. And all it took was her risking her life. Naww. Whether Lisa ‘develops’ her grittier side or it has been there all along is a moot point. Jefferies is seeing her anew, perhaps in the same way Hitchcock viewed the ideal woman: beatific, self-sufficient, and, as Edward White suggests in The Twelve Lives of Alfred Hitchcock, “with access to mysterious reserves of instinct and intuition."

The Ladies Across the Street

As Lisa supersedes his expectations, so do the women outside his apartment; characters who were one dimensional window dressing are suddenly imbued with story and depth. Miss Torso (Georgine Darcy), is first seen through Jefferies’ eyes as ballet dancing eye-candy, “a queen bee with her pick of the drones." Greater observation (and input from Lisa) forces him to realize that she is “doing a woman's hardest job — juggling wolves." And then there’s Miss Lonely Hearts (Judith Evelyn), a middle-aged singleton seeking a partner. Jefferies watches as she plays at having suitors for dinner, pouring an extra glass of wine and speaking to an empty chair. To Jefferies, the sight is both uncomfortable and pathetic, but develops into something more complex as he witnesses her increasing loneliness, unwanted advances, and a decision that suicide is her only escape from isolation.

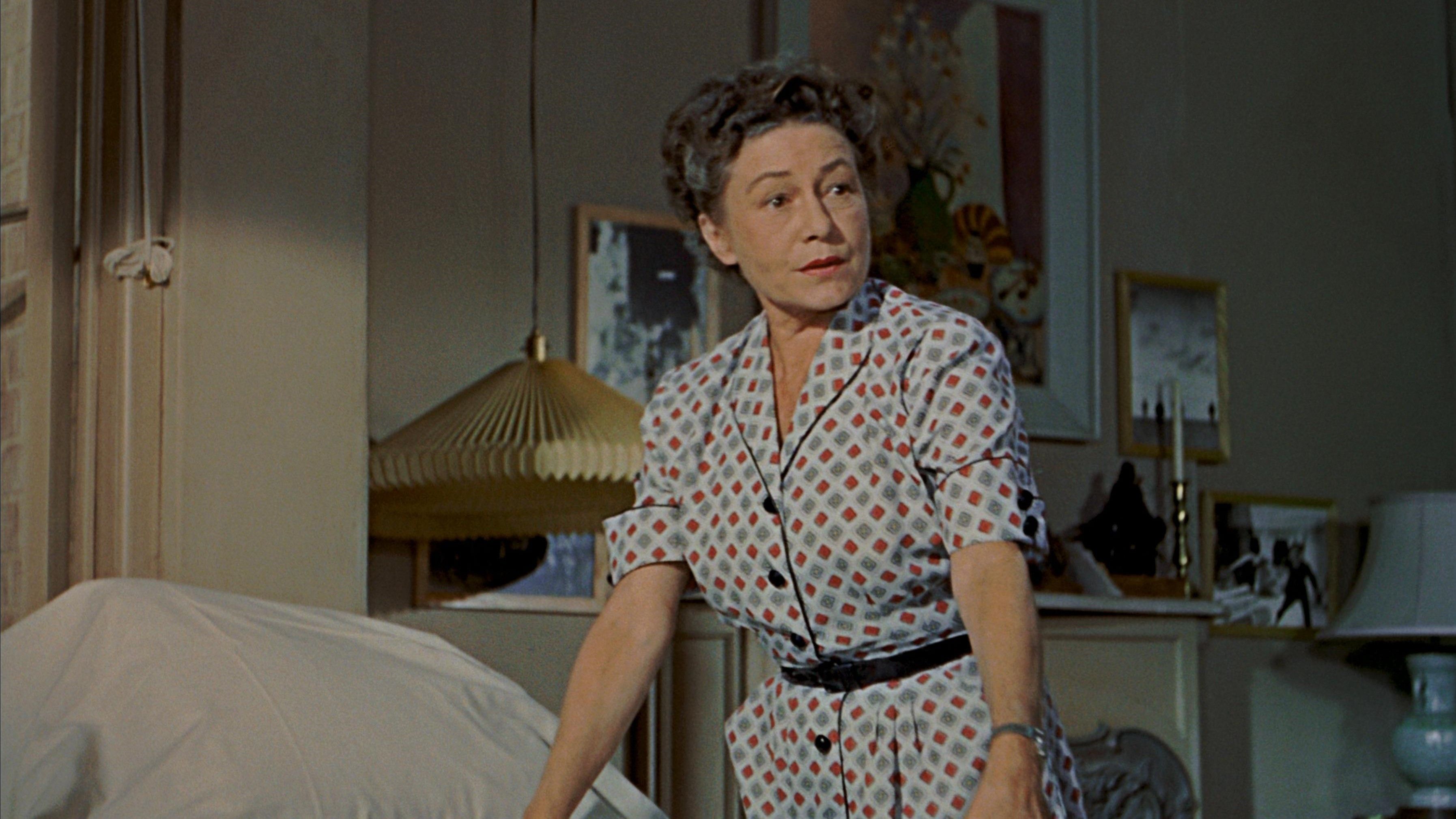

And Then There's Stella...

And of course there’s Stella. Practical, no-nonsense, unconcerned with appearances and more than happy to call a spade a spade, or in the case of Jefferies, a man an idiot. “I’ll spread a little commonsense on that bread," she states, mocking him for his dismissal of Lisa, all the while taking the prospect of murder in her stride. With the constitution of a rhino, speculation about the dismembering of bodies and the extent of blood splatter is simply “what we’re all thinking."

In the end, it is Stella and Lisa who become the film’s dynamic duo, teaming up to hunt for clues while Jefferies watches on. By this stage a changed man, he does so in awe rather than impotence.