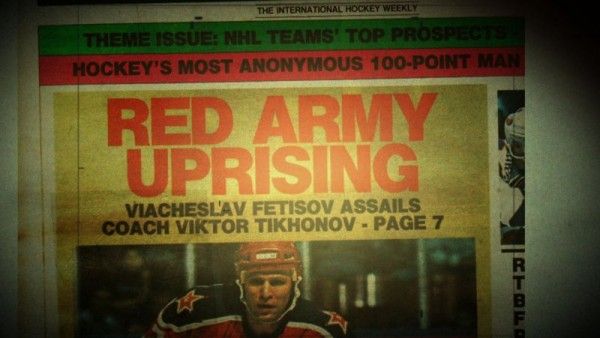

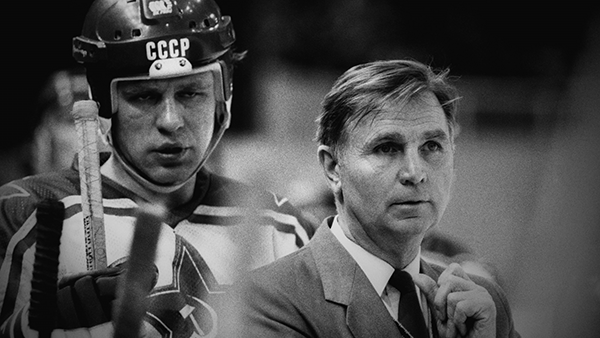

Gabe Polsky’s new film Red Army (check out Matt's review) is an exhilarating documentary about the Cold War on ice and how an incredibly oppressive system produced one of the greatest teams in sports history: the Red Army Hockey Team of the late 70’s and 80’s. The story is told from the perspective of its former captain and star defenseman, Slava Fetisov, who was at the center of an extraordinarily talented group of players – Sergei Marakov, Vladimir Krutov, Igor Larionov and Alexei Kasatonov – known as the Russian Five. Fetisov’s impressive career took him from national hero to political enemy to Russian Minister of Sport under Vladimir Putin.

In an exclusive interview, Polsky spoke about using hockey as a window into a larger personal and political story, what inspired him to structure his documentary around the legendary Red Army Hockey Team and one of its greatest players, why Fetisov was an interesting interview subject, the challenge of finding the right archival clips to give people a sense of the place and setting, the visionary Anatoli Tarasov and what distinguished the Soviet style of play from that of North America, Werner Herzog’s role as executive producer, the impact of hockey on Polsky’s life and its influence on him as a filmmaker, and his upcoming projects. Check out our interview after the jump.

How did this project come together for you and what made this a story you just had to tell?

GABE POLSKY: It was sort of a long time coming. My parents are from the former Soviet Union, from Ukraine, and I grew up wanting to be a professional hockey player. Growing up, I didn’t know very much about my heritage and the Soviet Union and things of that nature. But when I saw the Soviet Union play hockey for the first time, to me, it was profound. The way that they played was like a cultural experience. It was like seeing magic. It was like a religious experience. The way that they were creative and brought sports to a new level creatively was incredibly inspiring and made me curious about a lot of things including my own background. When I looked into the story of Soviet hockey and its players, I realized that it has nothing to do with hockey. It was a larger story using hockey as a window into the story of the rise and fall of the Soviet Union, the Russian people, with friendships and betrayals, paranoia and oppression, and the meaning of sports to people and nations around the world, and how sports was used as a political tool. The players were pawns in a much larger kind of system. I thought that was incredible, and all these things, and everything that was more than hockey, is what really led me to want to tell this story.

What inspired you to structure your documentary around the five key players and then tell it from the perspective of Slava Fetisov?

POLSKY: What I found interesting about Slava Fetisov was that he went through three different generations of Soviet hockey. In the late 70’s, he experienced the Miracle on Ice, and then in the 80’s became with his teammates the Russian Five, the most dominant team in the history of hockey, and then helped bring down the hockey system when the Soviet Union collapsed and became one of the first players to play in the NHL, and then ultimately came back to Russia. So, it’s a sweeping story that I felt was just perfect. I don’t want to get into being too hockey centered, but I just felt like the late 70’s and 80’s into the 90’s was the right time period to tell the story. I also talk a little bit about the Stalin Era that kind of braids through the Khrushchev Era.

When we first meet him in the film, he is flipping the camera off while he checks his cell phone and ignores your questions. What was it like working with him as an interview subject and was it hard to get his cooperation?

POLSKY: He is like he is on the screen. I had a real hard time reaching him initially. I called him a bunch of times. He kept refusing, and finally on the last day of the shoot, he agreed to meet me for 15 minutes. And then, even right off the bat, he was standing closer than other people stand to me. (Laughs) He just is a presence. He can be very charismatic, but he can also be quite aggressive, too. I knew right away, the first time I met him, that this guy was going to be an interesting interview. That initial 15-minute interview lasted 5 hours and he opened up to me. He said it was more than he had ever opened up to any journalist. He felt that I was prepared, that I knew what I was talking about, and that I had a level of understanding of both the Soviet Union and their hockey style. But it was fun. It was like playing hockey against a guy who was exceptional. The interview was tricky, but I knew it was going to be good.

He’s obviously fluent in Russian, but he also speaks English as well. Why did you decide to do the interview in English?

POLSKY: Obviously, his Russian is quite a bit better. I wanted him to speak English because I just felt that the North American audience is an audience that I really wanted to get for commercial reasons, and also I’m American and I wanted my friend and people [to see it]. I didn’t want it to be a film for Russia, although I did show it there and they absolutely loved it.

I’m not much of a hockey fan, but I loved the clips that you used. They were wonderful in terms of showing the players’ strategies and illustrating how creative they could be collectively and how they played as a unit.

POLSKY: It’s funny that you say that, because most people who come up to me after these screenings are people who aren’t really hockey fans, and they say the same thing that you’re saying. And the reason is because when people do something extraordinarily well, it’s self-evident. It could be art. It could be a circus, whatever it is, where people are doing incredible things. It’s self-evident. You know that it’s beautiful. You know that it’s very difficult, but it looks easy. What these guys did collectively was extraordinary and never seen before and never repeated afterwards.

How was the sport of hockey used in that era to promote and export the image of a successful U.S.S.R.?

POLSKY: Well basically any expression from film to chess to ballet to literature is interpreted by people. People watch things and they say, “Oh, okay, that’s how that culture is.” It gives messages. Sports is like literature. People watch it and if it’s beautiful and it’s non-violent, whatever messages that you see, people can read into it and say, “Wow! You know what? Whatever they’re doing over there, it’s extraordinary, and maybe that culture is superior to ours in certain ways.” For instance, if they see North American hockey and they see violence and brutality and it’s not so interesting, that sends a message too about your culture. And so, more than people think, sports delivers a message. It’s not just about winning and losing, although that’s important. It’s about other things, too. It demonstrates how it can say certain things about your culture and your society.

How hard was it to find the archival footage you were looking for and were the Russians helpful with that?

POLSKY: It was pretty hard. I had to go to Russia to see some of it because I wasn’t really getting anything. When I went over there, I would ask them about the footage, and they would say, “Why are you here?” because they don’t want to be giving anyone’s footage. I told them I was making a hockey film and they opened up. I speak a little bit of Russian. So, they showed me old films, and I would look through things on a Steenbeck machine and roll through footage. I found a lot of stuff that’s never been seen before. That was the goal: to not use cliché Cold War footage but give people a sense of the place and setting. It’s a field you still need. At first it was a lot of fun, and then later it became a little bit intimidating. “Oh my God, I’ve got so much footage. Where am I going to put it? What am I going to do?” I ended up really only reviewing about 20 to 30 percent of what I had. So it was a task.

When you were a hockey player in high school and then later at Yale, how did the Soviet hockey style influence you and the way you played? What did you admire about their hockey players?

POLSKY: I was more of a skilled player. I liked making plays and being creative out there, and then being smart with the puck and using my teammates. It was difficult because very few people think that way in North American hockey. It’s just not taught. You’re taught to play a role and be aggressive. Very few coaches emphasize creativity or creative thought. And so, for me, it was a very frustrating process. I just had a really hard time with my coaches. I found it frustrating. It’s just not set up that way.

What was your position?

POLSKY: I was a forward.

What do you feel it is about the training in the Soviet system that set them apart from other teams in that era?

POLSKY: First of all, they trained using a very unique style. They would do somersaults, and carry each other, and move weights around in crazy motions and tires on the ice. It was very unusual. You don’t see that in North America. Also, there was a lot of weaving and passing and puck possession, and they were taught that the player was the servant of his teammates. It was about possessing the puck and using your skill to keep possession of the puck. In North America, it’s not really about that. It’s about shooting and individualism. And people skate in straight lines rather than sort of weaving. I found it’s not as fun to play that way either. If you’re a skilled player, you want to use your skill, not just hit the puck.

What do you think distinguished the Soviet coaches from the North American coaches?

POLSKY: It’s like night and day. First of all, Anatoli Tarasov, the guy that created the Soviet style of play, was a visionary. He was a creative thinker. He studied ballet and chess and art and read a lot. He created the style that I was telling you about. In the U.S., coaches could be the father next door. They had no formal training. They’re like old hockey players. They don’t go to school and study. There (in the Soviet Union) it was a science. In order to be a coach, you had to study in school. And again, like I said, there was less emphasis on culture and creativity and the collective. They weren’t visionaries. They’re not like deep thinkers. They don’t go to kids and try and encourage them to be creative and bring out the best of kids. It’s like they want you to play a role, and they want you to just do what they say, and it’s not necessarily elevating any games or making anything interesting to watch.

How did the hockey coach you had as a young person who came from the Soviet Union inspire you and make you aware of the expressive possibilities of the sport?

POLSKY: He taught us to look at the game differently, not just in training with a lot of jumping exercises, but kind of a different way of approaching your body and being more of a gymnast. He taught us to play other sports. It was important to play other sports so that you can develop various balances and awarenesses. I guess the prime example is in North America there’s a thing where if there’s no opportunity to move forward with the puck, then a player is told to dump the puck into the other zone. Just give up the puck and dump it in. Give it to the other team. And to the Soviet mentality in coaching, it just doesn’t make any sense. If you’re a skilled player, why are you going to give the puck away to the other team? Just give it away, right? They’ll turn back and pass right back to their defensemen and try and generate another play if it doesn’t work. And so, to me, it didn’t make any sense. Why would I just give the puck away to the other team? Why can’t I just turn around and pass it back and develop another attack? And that’s a fundamental difference that just kind of explains everything.

What do you think is the most important thing to have come out of the Soviet sports system of that era?

POLSKY: Individual skills were better. They were better skaters and they played a collective, beautiful game that was focused on possession of the puck and passing. It was almost like jazz, too. They could go anywhere. Instead of playing in straight lanes, they could play anywhere on the ice. And not only is it much more fun to play that way, but it’s more fun to watch. To me, it was astounding that the North Americans… I just didn’t understand as a kid why they didn’t teach those kinds of things, too. If it’s better, why not teach it? Maybe they just didn’t know how to do it.

What impact has the sport of hockey had on your life and would you say it’s as much of an art form as filmmaking?

POLSKY: Oh yeah. A lot of what I know as a filmmaker is because of hockey. That’s teamwork, and being able to collaborate with people, and be creative with them, and get the most out of everybody. Everyone’s got different talents, and you’ve got to bring out the best of everybody, and use your strengths and work together, and try and evolve it rather than do what was done before you, and to push into new areas. I’ve had a lot of coaches in my life, but I’ve only had a few very good ones. So, I try to take from the best ones and apply those to what I do and think and with anyone I work with in terms of how to motivate people and work with them.

How does the final film compare to what you originally envisioned?

POLSKY: Well, I had a vision, but I didn’t have a specific one. I knew I wanted it to be a profound film that was not about hockey, and that was unusual and interesting and had a strong dynamic range of humor and heartbreak, a soul. I wanted to really capture what the Soviet experience was and is. I didn’t know exactly how I was going to do it, but gradually the story got more and more shape and I got there. But it was very different. I didn’t really have huge expectations. I didn’t have a strict script, because I had to discover a lot of things. I didn’t know what these guys were going to say.

What did you learn about yourself in the process of making this?

POLSKY: You learn your strengths and weaknesses more. I mean, I’ve made other films also, but you’re tested. Anytime there’s a challenge and you’re tested, you learn about yourself. I was challenged every day on this film and I was just constantly learning my strengths and weaknesses.

Can you talk about Werner Herzog’s role as executive producer and how he became involved?

POLSKY: He’s been a steady source of inspiration to me based on his work, and I worked with him previously on Bad Lieutenant which I was a producer on. We maintained a friendship. He’s a guy that I really wanted to share the work with and see what he thought, so I showed up when I was further along. He got very excited about it and felt that I was saying something deep with it and we talked about it. He said, “Listen, anyway I can help you, I’d love to help. I believe in this film. I believe in you.” I was thinking about it and I said, “Listen, I’d be honored for you to be an executive producer on this.” Since then, he really has given me some great advice in moments of adversity. Even as I finished the film and was trying to get it into some festivals and so on, I had some adversity, and he really gave me some good advice and helped me get through some of the stuff.

I know you have a number of projects in development. Can you talk a little about what you have coming up next?

POLSKY: I’m writing and putting together my next few things. Even during the Red Army process, I’ve been writing and developing things, so that now that I’m done and with efforts supporting it throughout this process, I’m armed and ready to go with some things that I’m really passionate about. I can’t really say very much more. Some of the stuff I’ve been controlling for a little while.

Is there anything you’re excited about that you’d like audiences to know about?

POLSKY: Oh yeah. I’m very excited about some of the novels that I have adapted. I think they’re equally as powerful, if not more. Going After Cacciato (by Tim O’Brien) is something I’m very passionate about. I’m doing the Dorian Doc Paskowitz biopic (about the surfing legend). The Untitled Albert Einstein Project is amazing, but the person that controls it, because there’s always a person that controls the project, is Gigi Pritzker. You should go talk to her and ask her what’s going on with that. Flowers for Algernon (by Daniel Keyes) is also something I’m excited about, but I can’t say very much about it. They all have something similar about them in that I think they’re profound stories that have a soul. God Is My Broker is not happening. With The Master and Margarita (by Mikhail Bulgakov), there’s a guy named Scott Steindorff who’s in control of that. You should call him and ask him.

Is there anything else you’d like to bring out about your documentary that maybe I haven’t touched on?

POLSKY: You asked amazing questions that were very different than normal, so I appreciate that. It’s amazing what you asked for somebody who doesn’t like hockey. Even people who love hockey, our own fans, didn’t ask these kinds of questions.

I don’t dislike hockey. I just don’t know a lot about it, but I appreciated the physicality of the Russian team in those clips you chose and the grace, finesse and the whole psychology behind their teamwork. No matter where they were on the ice, they were one. Whereas when I’m watching Canada and the U.S., it seems so brutal.

POLSKY: I’ve been thinking of a good analogy for the difference. It’s almost like either you want to eat at McDonalds or you want to eat at a Michelin four-star restaurant. That’s what it is.

Red Army is now playing in NYC and opens in L.A. December 12th. The film opens in more theaters January 23rd.