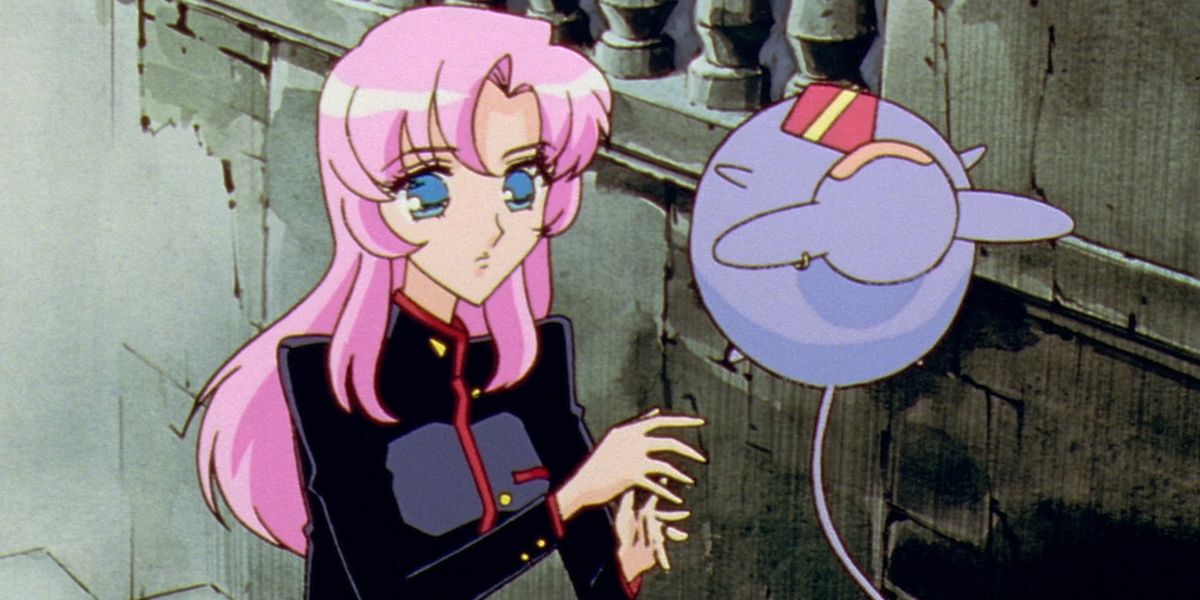

Revolutionary Girl Utena is a title most anime fans are familiar with. Released in 1997, on TV Tokyo, the show is one of the most influential of the mahou shoujo, or magical girl genre. It is frequently listed as an anime classic of the 90s, alongside series like Neon Genesis Evangelion, Cowboy Bebop, and Sailor Moon. However, despite being a critical darling, Revolutionary Girl Utena remains a criminally underwatched masterpiece, at least in the West.

The show’s heavy symbolism and legendary weirdness is often enough to scare more casual anime fans away, and for years Utena was known around the internet only as “that anime in which a girl turns into a car,” in a reference to a scene from the 1999 movie Adolescence of Utena. Besides, due to its heavily erotic subtext (or, sometimes, just plain text), Utena was too hard to adapt for children, and thus didn’t air on major networks, like Cartoon Network. Unlike other cult classics that made the jump to the mainstream, the show remained restricted to the circles of die-hard anime fans, especially those that are also part of the LGBTQ+ community, who identify with the series’ approach to topics like homosexuality and gender performativity. But is this underground status really enough for Utena? Or is it time for more people to start watching and appreciating this 90s classic as the magnum opus that it is?

To answer these questions, let’s first take a trip to the past. In 1997, Sailor Moon aired the final episode of its last season, Sailor Stars. About the same time, Naoko Takeuchi published the last chapter of the Sailor Moon manga series. First published in 1991, Sailor Moon revolutionized the magical girl genre by incorporating elements of transforming warrior shows like Kamen Raider and Super Sentai and of 90s girl power culture to the traditional format of the young girl gifted with magical powers. It was a hit. The Sailor Moon franchise now comprises hundreds of TV shows, movies, stage adaptations, comic books, novels, video-games and so on. Exported to North America, the show paved the way to many other series, from Cardcaptor Sakura to Puella Magi Madoka Magica, turning magical girls into some of the most well-known anime archetypes in pop culture.

Sailor Moon influenced many of the magical girl anime that came after it, especially the ones featuring groups of evil-fighting teenagers in stylized school uniforms. In the West, the show’s influence can be felt in cartoons ranging from Winx Club to Star vs. the Forces of Evil. But, most importantly, from the production of Sailor Moon emerged a new artist collective called Be-Papas. Formed by Kunihiko Ikuhara, Chiho Saito, Shinya Hasegawa, Yoji Enokido, and Yuichiro Oguro, Be-Papas would enter (and subsequently leave) the manga and anime world with the release of its only collective creation: Revolutionary Girl Utena.

Saito signed the manga that came out in 1996, and Ikuhara wrote and directed the 1997 anime series. Alongside Hasegawa and Enokido, Ikuhara spent a long time working as a director on Sailor Moon, particularly on the show’s second season, Sailor Moon R - the one with girlfriends Michiru and Haruka that were turned into cousins in the English dub. Having recently come out of such an important magical girl show, what else was the Be-Papas crew to do but turn the genre on its head and use it to create something entirely new?

The story of Revolutionary Girl Utena begins with a flashback: as a small child, Utena Tenjou lost both her parents and, with them, her will to live. Her life was saved by a prince that gifted her with a rose crested ring. Charmed by this act of kindness, Utena vowed to become as valiant as that prince and to meet him again some day. Years later, now a 14-year-old student at Ohtori Academy, she is accidentally drafted into a dueling club while trying to protect a girl, Anthy Himemiya, from an older boy that was abusing her. As it turns out, all members of the club - who are also the school’s much feared student council - have a ring identical to the one Utena got from the prince. The prize of their duels is the hand of the Rose Bride, Anthy herself, who is said to hold the power to revolutionize the world. As she dives deeper into this strange secret society, Utena falls in love with Anthy and comes to know a world marked by manipulation, abuse, trauma, lost innocence, and shattered dreams - an analogy for the process of growing up.

Revolutionary Girl Utena did for magical girl anime what Neon Genesis Evangelion did for giant robots: it took an already familiar story format and used it to ask existential questions about what it means to become an adult and find your place in a cruel world. But while Evangelion asked these questions from a male perspective, Utena privileged a girl's point of view. And, thus, the show deals with themes like gendered oppression, gender performativity, and historical abuse in all of its forms. The dashing, long-haired young men that are usually the love interests in shoujo anime, or anime targeted at teenage girls, are turned into cruel, abusive foes to be defeated in battle. The mean girls are, just like our heroines, prisoners of a system of oppression that condemns them for even the slightest faux-pas. The school is not a stepping stone for the real, grown-up world, but a prison commanded by a man - Anthy’s older brother, Akio - that takes pleasure in manipulating and controlling the youth. In order to become your own person, it is imperative that you leave it behind.

But the most important element to Revolutionary Girl Utena’s exploration of such themes is the characterization of Anthy and Utena herself. Docile, caring, frail, and blindly obedient, Anthy is the personification of traditional femininity. She’s perceived by the school council, as well as by Akio, as an object to be exchanged for power, not as a real person. For years, maybe even centuries, she has endured physical, emotional, and sexual abuse from her brother and many others. Throughout most of the show, she is seen as a shell of a person, with no interests but what Akio or her current “groom” wants. Worst of all, she believes this is what she deserves. It is only after she meets Utena that we get to see who Anthy is beneath the Rose Bride facade.

Utena, on the other hand, doesn’t adhere to the norms of traditional femininity. She’s the polar opposite of Anthy. She’s athletic, wears a boy’s uniform to school, and blatantly asks why can’t a girl become a prince. Unlike her classmates, who take Anthy’s continuous abuse as a mere fact of life, Utena is horrified by it and feels sickened by the Rose Bride theater the other girl puts on after she wins the duel. What Utena wants is to meet the real Anthy. It’s because she sees Anthy as a person that Utena is able to recognize the abuse she suffers and do what it takes to free her from her plight. It is because of the love she feels for Anthy that Utena is a “revolutionary girl”. And while the school council could only conceive of an illusory kind of revolution, Utena is able to enact real change.

Revolutionary Girl Utena tells its story not only through plot, but also through beautiful, surrealist and extremely evocative visuals. Influenced by the 1979 anime series The Rose of Versailles, that tells the story of a cross-dressing female general in pre-revolutionary France, the school council’s uniforms look more like 18th century French army outfits than like actual school clothes. Utena’s transformation sequence is basically her literally changing clothes in an elevator leading to the arena where the duels take place to the sound of the unforgettable “Zettai Unmei Mokushiroku”, by experimental movie and TV composer J.A. Seazar. The arena itself is a platform in the sky under an upside-down castle, symbolizing the upside-down fairy tale that Utena and Anthy’s story actually is. Anthy is frequently seen tending to her plants in a cage-like greenhouse, and the duelists fight for her hand with swords, or phallic symbols. It is also swords that represent Anthy’s ultimate judgment by a patriarchal society that sees her as undeserving of love and respect. And then there are the cars. The cars, in Revolutionary Girl Utena, are not mere vehicles, but symbols of power, sex, and maturity: driving a car represents control, and taking a joyride with someone usually entails a dangerous and manipulative game of seduction.

There is a lot that can be said about the symbolism and the underlying themes of Revolutionary Girl Utena. However, not everything has to be a philosophical debate. Another aspect of Utena that sets it apart from other anime is the show’s unique sense of humor, most of which revolves around Nanami, Ohtori Academy’s resident mean girl and one of the members of the school council. One particularly memorable episode, “The Cowbell of Happiness”, has Nanami turning into a cow after receiving a luxury cowbell as a gift. Unable to accept that the cowbell is not a designer necklace, Nanami slowly transforms into a farm animal, and it’s up to Utena to save the day. In “Take Care, Miss Nanami”, Nanami is convinced that someone is trying to kill her because of a series of freaky accidents involving various animals, including a gloved kangaroo that escaped from the school’s boxing club. In yet another episode, “Nanami’s Egg”, Nanami believes she has laid an egg. This one actually gets a little more serious than expected, delving into matters like female sexuality and slut-shaming.

The final episode of Revolutionary Girl Utena aired on TV Tokyo in December 1997. Almost two years later, in August 1999, Ikuhara directed a feature film based on the anime titled Adolescence of Utena. Without the constraints imposed by TV executives, the movie is way more explicit in how it deals with sex and sexuality. While the show only hints at a romantic relationship between Anthy and Utena, in the movie, the two girls actually kiss - perhaps even more. The lack of control over what can or can’t be shown also means the movie is way crazier with its allegorical imagery than the television series. Adolescence of Utena can be seen either as a retelling of the show’s story or as a direct sequel. However, knowledge of the original material is necessary to understand certain key aspects of the film.

Much like its predecessor, Sailor Moon, and its brother from another father, Neon Genesis Evangelion, Revolutionary Girl Utena became highly influential in the decades following its release. Animator Rebecca Sugar, in particular, is a fan of the series, and traces of Utena can be found in many of their shows. Pearl’s design and sword fighting style in Steven Universe bares a lot of resemblance to Utena’s, and the Crystal Gem’s relationship with Rose Quartz draws a lot from the anime. In the anime world, shows like Revue Starlight and Princess Tutu also owe a lot to Utena, both visually and plot-wise.

With an unhinged sense of humor, heavy themes, and a great reliance on symbolism instead of straight storytelling, Revolutionary Girl Utena isn’t always an easy watch. Still, if you manage to catch it at just the right moment in your life, it might just become your new favorite anime. Just keep an open mind and don’t be afraid to dive right into Be-Papas’ world of color and insane visuals. To make it easier for fans and newcomers alike (at least in the US), Nozomi Entertainment has uploaded all 39 episodes of the show to YouTube, where you can watch it legally for free.