Richard Jewell has a fascinating story. A security guard working the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta, Jewell discovered a bomb in Centennial Park and his quick-thinking and hard work helped saved lives. However, Jewell became the center of the investigation merely because he fit the profile of the “hero bomber.” Jewell’s life was turned upside down by the FBI and the media, and those are two institutions that need to be explored. The problem with Clint Eastwood’s new movie, Richard Jewell, is that as good as it is at showing Jewell’s heroism thanks to an outstanding performance from lead actor Paul Walter Hauser, for Eastwood, movies about heroes need villains, and Richard Jewell has some piss-poor villainy. Similar to Eastwood’s previous movie Sully, the bad guys are cartoonish caricatures meant to elicit sympathy for our hero while avoiding nuance, which is fine if you’re making a superhero movie for kids, but not so much when your film is ostensibly for adults. Paired with Eastwood’s cold, limp direction, Richard Jewell comes off as a story worth telling, but one that needed a better storyteller.

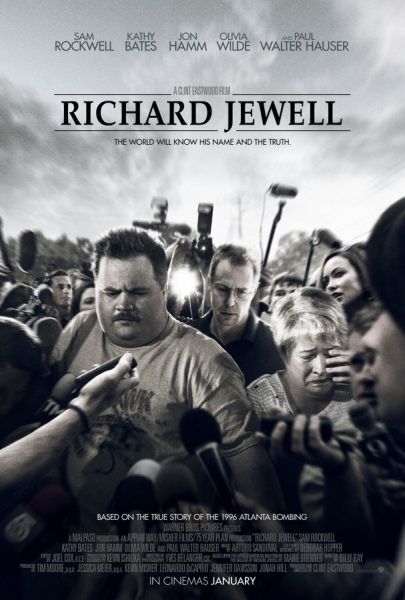

In 1986 in Atlanta, office supply manager Richard Jewell (Hauser) befriends small business attorney Watson Bryant (Sam Rockwell), but the two eventually drift apart when Richard leaves the attorney’s office to work as a campus security guard. Ten years later, Richard is working security at Centennial Park during the 1996 Summer Olympics when he discovers a bomb. Working with other officers, Richard is able to save hundreds of lives. However, the FBI, led by agent Tom Shaw (Jon Hamm), looks at Richard with suspicion and then Tom shares those suspicions with Atlanta Journal Constitution reporter Kathy Scruggs (Olivia Wilde), who trades sex for information. With the media and the FBI allied against him, Richard calls on Watson’s help and the two must stand against a system looking to railroad an innocent man.

There are two stories happening within Richard Jewell, but only one of them works. The one that works well is a story about a man who reveres law enforcement and genuinely wants to join their ranks only to be belittled and persecuted by that very system. It’s here in a story about your heroes not only letting you down but working against you that Richard Jewell has an interesting angle bolstered further by Hauser’s performance. To the film’s credit, Richard Jewell doesn’t try to paint its title character as a victim/saint, but rather a flawed man who’s sweet and a bit simple to the point where he doesn’t seem to grasp how much trouble he’s in. That tragedy comes alive thanks to Hauser’s emotional performance that rarely needs to go big in order to convey the character’s hurt and betrayal. You truly get the sense that Hauser wants to do right by Jewell not because he was a perfect man, but because he was a good man who, through no fault of his own, landed in serious jeopardy.

Unfortunately, that leads to the other story, which is about injustice, and Richard Jewell has no idea how to handle that one. If you’re looking for a story about injustice, then yes, what happened to Richard Jewell was supremely unjust. However, the way it plays in Eastwood’s film falls back to a problem of interpersonal relationships and bad actors removed from context and therefore reduced to dumb luck. For Richard Jewell, the FBI isn’t the problem; Tom Shaw is just a bad agent. Not all journalists are bad, but our main one, Kathy Scruggs, is ambitious, reckless, and cared more about applause than the truth (it should be noted here that people who worked with Scruggs take umbrage with her depiction). Even if you buy into the notion of bad actors, the way they’re depicted here is so shallow and one-dimensional that it renders their appearance comical and cheap. The gravitas of the situation is undermined by straw men rather than a mature look at how institutions fail.

I have no idea how Eastwood sees this picture in a larger context, or if he does at all. But art does not exist in a vacuum, and Eastwood, at this point in time and in this political climate, chose to tell a story about nefarious FBI agents and nefarious journalists teaming up to tear apart the life of an innocent white guy. I don’t know if Eastwood has a bone to pick with the FBI or the media or if Billy Ray’s script just renders these institutions as flat as the characters of Tom Shaw and Kathy Scruggs. But what I do know is that if you’re trying to tell a story about flawed institutions, this story doesn’t have the maturity to handle it. And if you’re trying to tell a story about injustice, then this feels like the All Lives Matter version of When They See Us, which understands that there are larger systemic forces at play than a couple of bad apples.

Setting politics aside, these issues are inevitable when a director doesn’t seem to take much care with the material. Richard Jewell was made in a matter of six months, and while the project itself has been in development for far longer, Eastwood’s take feels rushed and thoughtless. There are some choices that work, like having long stretches of the film take place in Richard’s home to show the character’s claustrophobia and being trapped by his situation, but so much of the cinematography and scoring feels phoned in and obvious. Hauser is the main spark of life holding everything together, but so much of the movie feels haphazardly cobbled together. For example, in the leadup to discovering the bomb, there’s absolutely no tension. There is, however, a macarena dance number in case you forgot the 1996 Summer Olympics took place in 1996.

Richard Jewell is emblematic of a large problem with Eastwood at this stage in his directing career, which his that he largely makes bland hero stories as a hobby. At best, you might get some stylish propaganda with a strong lead performance like American Sniper, but more likely you’ll get something like Sully, which rips from the headlines to show a hero who is persecuted by the system yet perseveres thanks to being the hero. Eastwood’s movies don’t really demand more than that of their audience, and they certainly aren’t demanding him to surprise us as a director, which is a shame when you’re working with rich material like you have with Richard Jewell. Ultimately, it feels like a waste and like the point of Richard Jewell isn’t to provide insight into its main character or institutional failure, but rather to give Eastwood something to do in his twilight years.

Rating: C-