Opening this weekend is director Anthony Hemingway‘s World War II action-drama Red Tails. Produced by George Lucas and Rick McCallum, the movie is based on the real-life story of the first all African-American squadron and their fight to defend our country. They were given second-hand planes and the most dangerous missions, and it makes their story all the more incredible. Red Tails stars Terrence Howard, Cuba Gooding Jr., Bryan Cranston, Brandon T. Jackson, Nate Parker, David Oyelowo, Ne-Yo, Elijah Kelly, Tristan Wilds, Cliff Smith, Rick Otto, Daniela Ruah, and Michael B. Jordan.

Last week I did an exclusive phone interview with McCallum. During our wide ranging conversation we talked about LucasFilm's two decade quest to make Red Tails, how advances in technology helped make the film possible, the 11.1 sound mix, and what being a producer really means. In addition, with McCallum producing the live-action Star Wars TV series (Star Wars: Underworld), he talked about what fans can look forward to, why it's still not filming, and revealed "It's Empire on steroids." Finally, we also talked about Lucas' future as a director, what props he owns, whether or not the 3D release of The Phantom Menace is the same cut that's on the Blu-ray, if we'll ever see the original trilogy on Blu-ray without any corrections, and so much more. Hit the jump to either read or listen to what he had to say.

As usual, I'm offering two ways to get the interview: you can either click here for the audio or the full transcript is below. Red Tails opens this weekend.

Collider: You talked a little bit about Star Wars yesterday. Are you surprised how many sites pick it up, or is this par for the course for you?

Rick McCallum: It’s par for the course. The thing is, producers don’t really publicize movies, do you know what I mean? The only reason that I have any chance of doing that with Red Tails is probably because of the Star Wars association, and I kind of understand what the rules are so I get it.

One of the things that fascinated me when reading about the movie is that you guys are doing this Auro 3D 11.1 mix. Can you talk about this mix and how it’s different from previous sound mixes?

McCallum: Well what it does is it adds additional speakers up in the ceiling and it kind of refines the surround sound system to take advantage of, in our case, aerial combat. It’s a system that Barco is actually helping us do—we did the mix about three or four weeks ago just before Christmas in Brussels. Our sound supervisor supervised it with Barco and I think people are gonna be blown away. Unfortunately right now there’s only four cinemas in the United States, but I’m hoping by the 20th there’ll be either 12 or 13. There are certain kinds of films that this is absolutely a natural for, you know not all films, but in terms of—for us I would say sound is even more than 50% of the movie, it’s probably like 55% because we’re obsessed with it. There’s such a particular, peculiar, interesting subliminal sound to the P-51 that any pilot, anyone who loves aviation understands. In order to hear that kind of shrill whistle of the plane, you actually hear it in 11.1. That was one of the reasons, they came to us and said “Look we think we can get a couple of theaters, are you interested?” We tested it and it was just fantastic for our film.

You mentioned four theaters, are any of them in New York or L.A.?

McCallum: No, they’re mostly in the south. But if you give me a day I can get you a list of what I hope will be the theaters, cause they’re working on them right now.

Yeah I would personally wanna see it in 11.1. This is one of these projects that I’ve heard about for so long. How many years have you been on this project?

McCallum: Well I’ve been on it for about 20, George [Lucas] has been on it for 23. When I say I’ve been on it, George first told me about it in 1990. We were starting to get a group of fantastic writers on Young Indiana Jones Chronicles and about 1992-1993 we decided we’d ask one of our writers to give it a go. I don’t know if you know the whole history, but one of the biggest problems was that everybody wanted to do the full story, which is the Tuskegee airbase, the training, the racism, everything they went through which is a movie in itself, and then when they went to Africa, how they got to Africa from Italy, that period of the war when America and Britain were losing 50-60 bombers a day which is like 500-600 kids a day, and when finally the army realized that they had no other choice but to use these guys because they were like the only qualified pilots left. That’s a film in itself, and then of course once they went back and had to deal with the segregation and racism after having served their country. So you have these three big films, and of course everybody wants to do the Lawrence of Arabia version. They wanna do the Martin Luther King version, you wanna do the whole story, the big 3-4 hour epic, but it just became too unwieldy, too different stylistically.

What happened is when you struggle for that—you know of course every director wants it to be the biggest film of all time—so you’re always struggling to try everything, and then everything gets shortchanged. So finally after we finished Episode III in 2005 we were developing a live-action Star Wars TV show with a lot of great writers and we just said, “Nope.” George said, it’s kind of like what he had to deal with on his own with Star Wars, he did this whole backstory, knew everything, and he said, “No, I’m gonna take the middle section because that’s the one I know I can make and it’s the cheapest and most cost efficient that I can do the effects on,” and that’s basically what we said, “Let’s just do the dogfight part. Let’s do the action-adventure film and then we’ll do a huge documentary that explains the history of who these guys were, the story of what they went through in Tuskegee, what happened when they came back to the states, and just stick with the entertainment film which is the middle section.” Believe it or not it just takes a long time, and plus we had this little thing called Star Wars in the middle of it all. So even though we were thinking about it, talking about it, it wasn’t until we were really free from Star Wars that we said, “Oh yeah let’s get back into this.”

How did the advances in technology in the past few years possibly help or shift the telling of this story?

McCallum: Well I wouldn’t say there was anything revolutionary in terms of technology except for the cost per shot ratio. Had we done this 10 or 15 years ago, we would’ve been locked into ILM only being able to do this. What happened at this point is, by serendipity happening not until 2010-2011, what we were able to see were a number of visual effects houses, a number of a new generation of artists that had entered the workplace all around the world. While we were shooting the Czech Republic we met a company called UPP, they have about 100-120 artists, and they were starting to do astonishing work for television and some major breakthrough in 3D matte paintings. They had never done a film of this size, and they couldn’t do a film of our size—cause we have over 1600 visual effects shots—but we felt confident that they could do somewhere between 400 and 550 shots.

There was another company called Pixomondo in Germany and they had done a World War I German film called The Red Baron. They had done a huge experimentation in cloud manipulation—all digital—that we thought was really, really interesting and unbelievably cheap, so they came onboard. They hit another benchmark altogether, they did more shots than anybody; they ended up doing about 575 shots. There’s a wonderful company in Mexico and Canada and a company we’ve always wanted to work with in Austria called Rising Sun when we were doing Star Wars. They had all, during the last four or five years, found a level of talent and manage their companies well enough that they’re starting to be major players. It’s like when you saw Inception, that was done by a relatively small house in London at the time, but [it was] astonishing work. Normally if you had seen that you’d have said, “No, there’s only three companies that could’ve done that. Weta, Sony ImageWorks, or Industrial Light and Magic.”

That’s what happening now, there’s a worldwide group of people—still limited, because it’s such a particularly difficult thing that you’re asking, you’re asking for an engineer to be an artist. You’re dealing with a guy who understands physics, science, and math at a level that’s incompatible with a normal person, but at the same time who’s gotta be an artist. He’s gotta have a sense of painting, of history and what things do, of images. It’s very hard to find that kind of person, but now there’s so many different schools, there’s so many people that are interested in film and especially in terms of the technology side of film, that suddenly the fruits of everybody’s labor is really starting to manifest itself all across the planet. I mean China, we had about 35 full shots done out of Pixomondo’s offices in China. Very, very promising. They’re probably five, seven years behind but they’re gonna get there and it’s gonna happen unbelievably quickly.

The reason for all of that is how do you drive the cost down? How do you get a writer to be able to sit down with a producer and director and write anything that’s in his imagination? Or a director to allow him to be unlimited in the size and scope of what he wants to do, and find a way in which you can utilize the resources around the world to make it happen in a more cost efficient way. That’s the whole game plan. And one of the problems we had too at the particular time—which forced us into this position—was ILM was completely filled up. It was booked for two and a half years. They were doing Pirates and Transformers and every big film, so we had no other choice but to look around the rest world.

Which is kind of funny when you think about it, that you guys had to go somewhere else.

McCallum: Well what we did is, in order to make it work we knew we needed a full—not a trim down—but we needed a full team at ILM to be able to supervise all seven visual effects houses, and also to do the much more complicated shots. So ILM did about 100 of the most really complicated, computer-intensive shots, and they were able to work so closely with everybody that it’s seamless in terms of each sequence in relationship to how all the shots look. It’s still not at the level that we would yearn to be at, which is absolute total photorealism, but that’s not there for anybody yet. That’s still another 3, 4, 5 years away. Right now you can get very, very close, closer to what we could if you wanna spend 2, 3, or 4 times the amount of money; we didn’t have that as a more modest budgeted film. That’s what the dream is for everybody, how do we get absolute total photorealism at a cost that’s kind of commensurate with some kind of fiscal reality that makes it work for everybody?

You’ve obviously worked on a lot of movies, what props do you actually have in your home?

McCallum: None. The only way I can stop people from stealing is also not to steal myself, and it’s one of the most difficult things. I have certain kind of things that are built, like set pieces, but I have nothing from Star Wars, I really wanted to be pure about that. I have a lot of merchandise from Star Wars, but I have not kept anything prop-wise. Once you open that little bag, it’s a really hard one because there’s so many people who yearn for just a small little piece. It’s like moon rock. I have a piece of a P-51 which is really meaningful to me, and I’ve got a piece of a B-17 that my father didn’t fly—he was a B-17 pilot—that I was able to get in England when we were shooting. But those are the only real things that have serious meaning to me. I mean all my Star Wars merchandise, the best pieces, I love, but nothing from the films.

What is, do you think, the prized possession of the merchandise that you have?

McCallum: My two favorite things are an R2D2 paper basket which I have in my office and my office at home, and my Star Wars Mr. Potato Head. Those are my two favorite, but I have a lot of stuff. Those are my two favorite things, I have no idea why.

Episode I recently came out on Blu-ray, and you guys are getting ready to do a 3D re-release. Obviously I’m a fan of you guys, I’m a fan of Star Wars and I know that George likes to tinker and change. Is the 3D re-release any different than what just came out on Blu-ray or is it the same movie just in 3D?

McCallum: It’s the same movie in 3D.

Do you think we’ll ever get the original trilogy and the prequels without any changes on Blu-ray, or is it never gonna happen?

McCallum: I would have to answer that officially it’s never gonna happen, but you never know with George. It’s one of the constant things that—let’s put it this way, it changes always. You never know.

Yeah I mean personally, as I’ve said many times on the site I have no problems with George changing the films, I just think it would be great if he would release the originals and that way everyone could have it, but that’s just me.

McCallum: I know, but I understand that completely. It’s just a question I can’t answer. Obviously I have my own personally feelings, I hope that he does it, but I don’t have major arguments with him about it. I think that’s a decision he has to come to on his own as time comes by.

I totally get it, it’s up to him. It’s his thing. You were a Naboo courier in Episode I, yet no cameos were made in Episode II or III. I have to ask why.

McCallum: Well I was so humiliated by my performance in Episode I that I only allowed them to use certain body parts in Episode II and Episode III. In Episode III at the very beginning of the film, there’s a clone that’s actually killed and ILM had an enormous amount of pleasure keeping me up on the wires. I’m flying through space screaming, and that’s me. In Episode II, my arm and my ankles and my feet were in the film. That was the extent of my body that I was willing to give up (laughs). I’m credited too, sadly.

I definitely wanna ask you a little bit about the live-action show. You mentioned yesterday that the idea is to get down to $5 million per episode, and I know you guys must be working on the budget now. How close have you guys been able to bring the budget down, or are you still so far apart that it just can’t happen yet?

McCallum: It’s so far apart, this is the best way to put it into perspective: we did Episode III—which is one of the larger of all the Star Wars films in relation to set construction, visual effects, the amount of visual effects and everything else—and that was made for $100 million which was unheard of even five years ago, because had it been made by any studio or anywhere in the United States it would have been easily double that price. So imagine an hour’s episode with more digital animation and more visual effects and more complicated in terms of set design and costume design than a two- hour movie that takes us three years to make, and we have to do that every week and we only have $5 million to do it. That’s our challenge. It’s not a challenge that I think can be dealt with in the next year or two years, I think it’s gonna be a little bit more longer term goal.

He’s come up with so many extraordinary digital characters that are onscreen for 30-40 minutes, well most people who love movies and kind of understand the process realize that if you do a character like Gollum or Jar Jar or any major digital character, that costs twice as much as having Tom Cruise in a movie. You get 150 people working for two years on a 40 minute performance and they all make serious money, you just add it up; that’s gonna be a serious $20-30 million character. That’s our problem, how do we get that down? How do we push everybody to get to another level?

Also, digital 3D matte paintings, how do we cut the time from 2-3 weeks to 2-3 days? On a television budget, on television screens it doesn’t have to be film res, but each one of these are major challenges for us. How do we get virtual set software? Because we can’t build any of this stuff. I mean we could do it if we did it in a traditional format where we have one set with all the characters, but George doesn’t work that way. We have 40-50 set pieces per hour, every minute and a half to two minutes there’s another set. Well we can’t build that and do that every week, that’s virtually impossible, so we have to come up with virtual set software and an environment that allows us to be able to do that on blue and green screen and be able to turn those backgrounds around really, really fast. We’re getting there, but it’s not perfect yet and it’s still too expensive.

One of the great things about Red Tails is we’ve met a whole other group of people around the world who’ve never had the resources or the tools or the access to the kind of gear that American visual effects companies have and they’ve had to cope and survive, and so we’re learning a lot from them also.

We’ll get there, I’m just not sure if it’s gonna be in the next couple of years.

What excites you most about the TV series? Also, a lot of fans are clamoring for something that’s a little more adult, a little grittier; as you said, the underworld of Star Wars. Is it darker than the movies or is it like the movies?

McCallum: No, no. It’s much darker. It’s a much more adult series. I think, thematically, in terms of characters and what they go through, it will be…if we can ever get it together and George really wants to pursue it, it’ll be the most awesome part of the whole franchise, personally.

Believe me, this is something I’ve been wanting to have happen for a very long time. I’m hoping that this all comes together.

McCallum: It’s Empire on steroids.

That’s what I want to hear! Did you see season one of Game of Thrones?

McCallum: Oh, yeah. Absolutely.

Obviously, I loved it, just like anyone else who’s watched it. I haven’t met anyone who didn’t like it. I don’t want to spoil it for anybody, but let’s just say a lot of stuff happens that’s not typical of a TV series. Is that something that you guys are thinking about doing, the way the arcs of characters were in that?

McCallum: Absolutely. Seriously, there were no holds barred, the writers went for it, George [R.R. Martin] set a standard. The original thing was, we kind of described it as “Deadwood in space.” That’s the kind of track we started heading for. Obviously, we changed it for where we couldn’t go in terms of language. It was to be serious performances, very complicated relationships, unbelievable issues of power and corruption, greed, vanity, pride, ego manifesting itself at levels that only equal the world that we live in now, but, as I said, on steroids.

By the way, I appreciate you answering my questions. You guys mentioned that you did 50 scripts. When you wrote that, did you write it in such a way that each season was 13 episodes or 22 or 24?

McCallum: One of the reasons HBO succeeds so well is that two things happen: they’re not 40-minute episodes, they’re 50-minute episodes so you actually get the serious character arc. You really have the time to be able to express yourself and let characters be real. And second of all, when you’re dealing at that kind of level like Game of Thrones, you’re doing it at 13 because that’s all you can do to make it really, really work well. When you’re stuck, when you’re forced into a 26 or 22 or 24, whatever the network bullshit is now, it’s very, very hard to keep that kind of level of quality, especially when you’re dealing with visual effects and fantasy. If you’re doing a courtroom drama, yeah, you can go for it, but not with this kind of stuff. Not if you want to be unique, bold, daring, provocative and extraordinarily original. It’s just too hard. It’s too much pressure on the cast, directors, everybody. Thirteen is good because you’re still doing, what we always try and do, like the networks force these guys to do this thing between eight and ten days, we need 15, 17, 18 days because we’ve got so many visual effects. You’re still shooting for 30 weeks a year and you need to let people breathe, have their time off, be with their families because this is total commitment. This is 16, 17 hours a day by the time you leave and get home. This is a really major, major deal for a lot of people. It’s like a Young Indy for us. Our goal was, how can we travel all around the world, make something that looks cinematic for the same price as Law and Order…not Law and Order, I can’t remember what the series was, but do it on a television budget where they shoot around the world, use major film directors, but do them for the same money that a typical cop show costs.

Does that mean that when you guys were writing, you were thinking 10, 13 episodes for a season?

McCallum: One of the problems that we have and one of the areas that we got to, for me personally, I know George was very fascinated about network television because the audience reach is so much different but then it became clear to us about two or three years ago after the financial crisis that literally the world of television is imploding, because it’s all based on smoke and mirrors. No one knows how to really judge who’s watching what or how many, but nobody can give up the Nielsen’s because without it, networks are going to fold completely, the advertisers will pull out. Everybody’s been living on this idea that they think they know what people are watching in the United States and I don’t think they have a clue. It’s like Mad Men. It was only last year that over a million people would see Mad Men and yet look at the profound impact it’s had on everything in television. Deadwood I don’t think ever got beyond four million viewers.

You can’t quantify how many people bought it on DVD or Blu-ray or downloaded it illegally on bit torrents and how many people passed on those files or those disks to their friends. It spreads.

McCallum: I know, and the thing is, no one has any clue. Let’s put it this way, it’s not that they’re dumb; they do have a clue. But they can’t deal with the reality of being really, truly clueless right now because if you do the whole system falls apart. The minute advertisers say, “Well, shit. There’s only really a million people watching my network’s show? But, Nielsen says it’s fifteen million.” Everybody’s got to live to this game, because otherwise the whole thing falls apart.

If I were an advertiser, the only place I would put my money would be on football games because thirty to fifty million people are watching these things right now and they’re not forwarding through the commercials.

McCallum: I know. Absolutely. And I don’t know if you heard about the Alabama game yesterday?

I haven’t heard the ratings yet.

McCallum: Oh, well, it was not just the ratings. What happened was, LSU decided that they would watch a film before the game and Alabama watched Red Tails and they used the mantra of, “We fight! We fight!” and they creamed them 21-0.

I did not know that.

McCallum: Yeah, we just found out today. I mean we knew that they were seeing the film. We knew the coach was using it to inspire the team and everything. I think LSU watched the Mark Wahlberg picture…

Contraband.

McCallum: Yeah, Contraband.

Yeah, that’s very funny. I would think that Red Tails would have been the better choice.

McCallum: Absolutely and they lost! But Alabama won and I think they found it really inspiring so everybody was really jazzed and pumped yesterday, last night when they won.

You’re absolutely right about these things, football and the next one is this influence of bit torrents, downloading, that’s the real future of this. I feel sorry for the guys. I wouldn’t want to be in the studio business now, I wouldn’t want to be in the television business, because how do you deal with all of that?

I’m going to cite another example that’s happening this week. In the UK, they’re airing something called Sherlock which people absolutely love. I love it. It’s not going to air in America until May. Many people don’t want to wait until May to watch something that could be spoiled for them by millions of people watching it in the UK right now. The industry has to learn day-and-date releases across all platforms.

McCallum: I know. It’s so amazing because we have two friends who just came in from London last week who have copies of Sherlock!

The new series, yeah.

McCallum: And they’re showing it to their friends here. That’s the trouble: once you take an individual and you give them the opportunity, but you take away the opportunity for him because you’re being dictated by something that you don’t believe, which again, there are issues of piracy and everything else, but everybody’s been on the fence because they’ve been burned for so long and they’re basically saying, “You know what? Fuck you! I’m going to show this to my best friend. This is cool.” The only thing responsible people can do to stop that kind of piracy is to do day-and-date across the world.

I’m of the opinion that we’re eventually going to get to the place where everyone understands that the smartest thing that a studio can do is day-and-date with obviously certain things, but with smaller budgeted movies, you do VOD, you do theatrical, you do TV, you do everything all at once for smaller things. For bigger things, you obviously just do theatrical.

McCallum: Yes. Absolutely.

Believe me, I see both sides of it. I write about this stuff every day. The day-and-date though, it has to happen. What is your typical week like on the job? That’s something I’m interested in. Are you in meetings all day?

McCallum: There are two things that I’ve been able to do, thank God, because of the gift that George has given me the last twenty years is I don’t do meetings. We have discussions usually while we’re walking. I don’t have to do emails, I don’t have to protect myself about anything, I don’t have any chain of command. My job is just to try and give everybody the tools that they need to express themselves. The average film has eight or ten producers on it. That is just in a world that would be unthinkable to me, because to me, to really be a producer of a film, you have to be a line producer. That’s the person who’s on the job every single minute, on the floor every minute giving the director and the crew all the tools that they need but doing it in a fiscally responsible way and being part of the actual day to day making of the film. Otherwise, it has absolutely no meaning to me to be an executive producer on a film that I have nothing to do with except come to the wrap party or the premiere on; it’s just meaningless. It’s also everything repugnant to me because I think it’s also one of the biggest problems with films. Nobody sets out to make a bad film, but so many of those compromises are made and often they’re made because of vanity, pride and ego.

I have heard so many horror stories from so many filmmakers off the record. Everyone wants to justify their job and why they have their name on a property. You have eight producers and everyone has an opinion and you water down something that started off strong.

McCallum: Absolutely and most of those people have no understanding of the actual process of day to day and the decision making that has to take place and the compromises that have to take place due to weather, money, anything. It’s easy to be a backseat driver. It’s even easier to be a backseat driver when you’re not even in the same car and that’s what the biggest problem is. Most of the people, when you see those credits, aren’t even in the same car with the filmmakers. And then the poor guy who’s the “line producer” who’s making everything happen for his director is not even given a real credit; he’s given a co-executive producer credit. Yes, you need somebody to have the idea, you need somebody who can deal with the studio and the normal things, but it’s too different of a credit. That credit is usually given to the executive producer. It’s not the producer. One of the great things is, you’re never a producer unless you’re making a movie. You know? You have to be producing to be able to be called a producer.

What other TV things are you possibly working for LucasFilm? What other stuff is coming together?

McCallum: Nothing right now because George is contemplating the idea of taking a little bit of time off right now. He’s got Clone Wars which he’s still doing, he’s got another season or two seasons of Clone Wars and he’s also working on an animated film which has nothing to do with Star Wars. So, he’s got his plate kind of full, but he’s going to take a little break after Red Tails and figure out what it is. I’m hoping that he will actually get back and start to do the more experimental, small, low-budget films that really is what he started off as. Star Wars was a curse and a blessing; a total blessing for him, but a curse to a lot of us who know him as a smaller filmmaker. I’m hoping he gets the opportunity to actually go back and do much more experimental work in the vein of not just THX, but pushing imagery, sound, music and telling different kinds of stories altogether. So, we’ll just wait and see.

As a fan of his early work, and he’s always talked about doing things like that, I’ve waited a long time to see him do stuff like that. How much are you whispering in his ears, “You know, George, it’d be cool to do that smaller indie movie you’ve been talking about for 30 years now. Hey, George, it’d be cool if you did this.” You know? Or is it that you can only whisper a little bit, otherwise he gets mad?

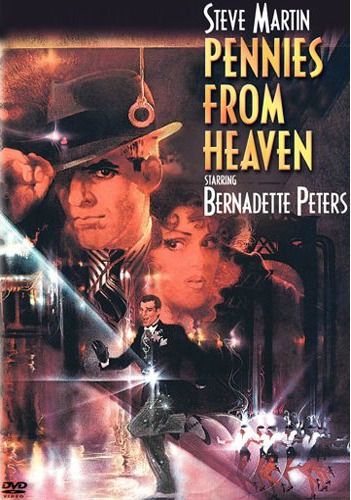

McCallum: Well, no. He doesn’t get mad. I’ll tell you what happened. A long time ago, I was doing a film with Jospeh Losey, a wonderful American director who was blacklisted. It was the first time he was coming back to the United States to do this movie. Unfortunately, the investors wanted us to get rid of the leading actress, Vanessa Redgrave, because she had some comments about Palestinians at the Academy Awards; we refused to do it. I was with the investors and basically I was given an ultimatum, “get rid of her or we’re not going to do the movie.” I called Joe and I said, “What do you want to do?” and he said, “Let’s go back home.” Home for me at that point was England, because my first film, Pennies from Heaven, was the most unsuccessful film of that year; almost bankrupted MGM. So I needed to go to a place where failure was awarded and that happened to be England. As long as the movie was good, people would let you work again even if the picture didn’t work. So I go back and I’m at Joe’s house and it’s the first time I’ve ever been up to his library, he was in a terraced house just off King’s Road. He had this beautiful wraparound bookshelf and there were hundreds of scripts. And then there was a very special little section of leather-bound scripts, which was only about eight scripts. He was almost 72 then. I said, “What is this?” and he said, “Well, those are the films I have made.” And then he looked and pointed all the way around and he turned as he did it and he said, “These are the films I still want to make.” And with George, it’s almost the opposite. Red Tails is the last of all the films that he ever said [he wanted to make]. He started 23 years ago on Red Tails and now he has fulfilled everything he set out to do, which no…very few filmmakers ever get an opportunity to do. He’s done everything that he actually wanted and planned to do, including more American Graffiti, including the revised version of [THX]. He got to be able to do everything that he actually wanted to do. Now, with this completed, a little bit of rest, now I think he can set upon the next chapter of his life and figure out, “Okay, do I have a new set of films, a new kind of films that I want to do?” And that’s what we hope and wait anxiously to hear from him on.

Yeah, [Francis Ford] Coppola is doing it right now, as well.

McCallum: Absolutely, absolutely. But he had to take a number of years off to actually say, “Wait a second, this is the world I want to live in. I don’t want to be in a star-studded system anymore.” And hopefully I’ll make the films cheap enough that if they don’t work, or if there’s enough people…there’s a great line in Citizen Kane when Orson Welles is up in his office and the accountant comes in and says, “My God, the way you’re spending money, this is crazy! This is nuts! We’re going to go bankrupt!” and he says, “Yeah, if we keep spending money like this, we can only last for the next 65 years.” Both of them have an opportunity now to do the kind of work that they want to do. It’s great to see Francis, I’ve never seen him so happy. He’s been to Romania, he’s been to Argentina, he’s all over the place. He’s working with young filmmakers who he loves and, whether you like the movies or not, it doesn’t matter. You wake up, and this is a gift that George has also given me, no matter how you look at it, you wake up in the morning and you can’t blame anybody else, that is the most perfect position you can be in the film business. That’s what true independence is when you fuck up and you fuck up but it’s only because of you and not because of an executive or system or thing made you make compromises you didn’t want to make. When you can’t blame anybody else, it’s a totally different kind of job.