An acclaimed feature film only available in a non-theatrical, non-traditional exhibition tells the story behind the making of Citizen Kane, casting A-list talent as the film’s key players, while diving behind the stories we already know to focus on the real life people and the sociopolitical context behind their decisions. I’m talking, of course, about RKO 281. The 1999 HBO film has now faded into obscurity — it’s not even available to stream on HBO Max — but at the time, received attention, critical praise, and a Golden Globe for Best Miniseries or Television Film. With Mank, a film about many of the same things, about to splash into the zeitgeist, we thought it would be interesting to examine this first fictional attempt at telling the tale behind one of the best American films ever made.

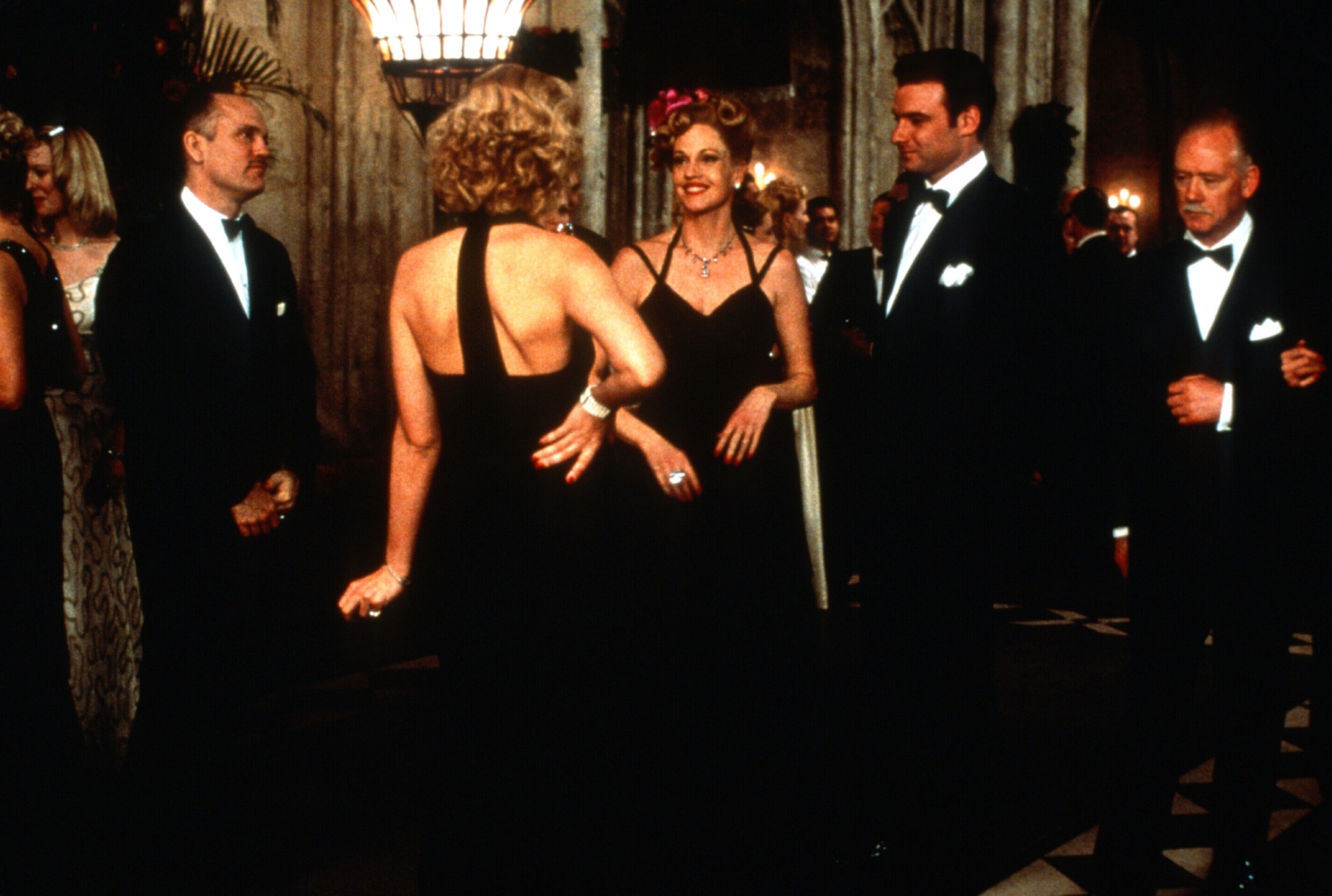

RKO 281, the title of which refers to Citizen Kane’s production number, focuses more squarely on Orson Welles, the writer/director/star of Kane. Liev Schreiber plays the wunderkind auteur, not quite going for a straight impression, but attempting to inhabit the alternating gravitas and vulnerability inherent in Welles. On the sidelines of Welles’ sprint to cinematic greatness? John Malkovich plays co-screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz (aka Mank). James Cromwell plays fearsome newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, whom Citizen Kane is not-so-loosely based on. Melanie Griffith plays Marion Davies, Hearst’s melancholy lover and quite the dreamer herself. And Roy Scheider plays George Schaefer, the president of RKO Pictures who wrestles between the safe commitments to his shareholders and the conscience-driven urge to tell a story worth telling.

On paper, this is an exquisite cast more than up to the challenge? In practice? Much like the rushed pace we see Welles film Citizen Kane in one key sequence (with Schaefer opining that Welles is “an anarchist who’s two days ahead of schedule”), many of these performances feel like they’re ready for the finish line without reckoning with the individual steps it takes to get there. Malkovich plays Mankiewicz like Malkovich, his familiar prickliness adding a sense of entertaining liveliness to the picture, but not much in the way of psychological reckoning. Scheider is obviously having fun affecting a Transatlantic “old school Hollywood accent” and chews up some of his speeches with fun spectacle, but an invisible pane of cliched glass seems to stop him from going deeper. As for Schreiber? I suppose I’m grateful he didn’t go full caricature of the screen legend’s easy-to-make-fun-of timbre and countenance, but I can’t help feel like the performance is constantly stopping itself from making any full choice. Schreiber is most effective at playing him like a dreamer, a voracious man with the power of spinning stories and magic tricks, a man who believes sincerely that “pretty speeches change the world.” But when the picture demands Schreiber tap into Welles’ temper, his megalomania, his disregard for those around him in favor of his own ego, I lose Welles completely, instead just watching Schreiber the actor perform an admittedly compelling exercise in “acting angry”.

To an extent, this shallowness is not solely the fault of the ensemble cast; it’s a feature, not a bug. Academy Award-nominated screenwriter John Logan (Gladiator) has turned in work guilty of all the standard biopic cliches; Walk Hard but earnest. We hop and skip through giant moments of history, cinematic revolution, and personal realizations like a platforming video game where the surface will fall away if we don’t move quick enough. The film runs under 80 minutes without credits, and while I normally adore a tight running time, director Benjamin Ross and editor Alex Mackie make this thing move much too quickly for any moment to have any staying power. And with this focus on speed, on breadth, on quantity of events not quality of events, Logan’s script must communicate with startlingly on-the-nose summaries, bluntly jamming character motivations and themes down our throats before turning them on a dime to shove another one five seconds later. One of the very first lines is Welles’ mom telling him, “Orson. Come into the light. Never stand in the shadows. You were made for the light. Always remember that. Now turn around and make a wish.” And it’s off to the races from there; we simply do not have time for nuanced, complex, showing-not-telling communication, so must settle for blunt grabbiness delivered bluntly and grabbily.

There are, of course, exceptions to these unfortunately mediocre rules. Cromwell and Griffith give remarkable performances, cutting through the first-draft clutter of their colleagues with beautifully contrasting studies of their subjects that represent a successful attempt to look under the surface, to imbue their “text only” screenplay with some subtext. Cromwell is clipped, mannered, and terrifying when he needs to be, utilizing Hearst’s textual hatred of swearing to make a statement about “pleasing surfaces” versus “bitter actions,” a gulf that comments on Hearst, Welles, and even RKO 281 itself with much-welcomed bite. Griffith, to my eye, gives the performance of the film, playing Davies with aching tragedy, yearning for comfort, finding herself puzzlingly appealed to Welles’ romantic criticism of her and her beloved-ish “Pops” Hearst. If the film had focused squarely on these two souls, examining what it’s like to have all your sins examined under the most highest cinematic rigor for the public, playing with varying expectations of sympathy vis-a-vis Hearst’s objective badness, it would’ve made a much richer experience. In fact, the film’s midpoint-to-end-of-second-act chunk tends to swing away from Welles And His Quest To Make A Movie, instead focusing on all kinds of fascinating, complicating, and gripping examinations of the rampant anti-semitism, homophobia, classism, racism, and viciousness of unchecked capitalism running amok in society at that time. These moments, where the picture dares to view its subjects with something more than rose-colored sunglasses, hit the hardest.

And these moments make me the most excited about Mank, and not to be too much of a Schreiber-as-Welles-esque romantic, but the most excited about the future of biographical cinema. At the time of its release, RKO 281 was considered a prestigious piece of filmmaking; now, it plays quaintly, overtly, and rife with potential not quite reached. But this potential, and the genuinely effective moments, are inherent in the film, begging for another storyteller, whether it’s David Fincher or the person reading this, to capitalize on them, focus in on what this film got wrong, and exalt them to Schreiber-as-Welles-esque heights. After all, pretty movies can change the world.