Rocky has remained an iconic and timeless film through the years for various reasons: establishing a franchise that is still running today, launching the career of Sylvester Stallone, serving as a mythical-like hero for the city of Philadelphia, and forming the template for the modern sports movie and motivational underdog tale. Ironically, a 1976 humble character drama about a low-level boxer who gets a shot at fighting the heavyweight champion transpired to these heights. When Stallone, who wrote the film and remained the author of the series, was also a struggling actor in the 1970s and was vaulted into super-stardom after winning Best Picture for his big break, it showed the profound ways in which life can imitate art. Let's not forget where the original iteration of a major franchise got its start — as a gloomy and gritty 1970s character drama.

1970s American cinema is an endlessly celebrated era for not just film, but art as a whole. The greatest compliment filmmakers can receive is that their work "feels like a '70s movie." This period, referred to as the New Hollywood, firmly instituted directors as the true authors of films, and produced some of the most lauded filmmakers of all time, including Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, and Mike Nichols. The average film from the "movie brats" was always nothing short of thought-provoking, either featuring examinations of the rotten core of society or character studies about deeply complicated people. The era became definable as the antithesis of its predecessor, Classic Hollywood. If Hollywood originated from glamour, then New Hollywood would deconstruct it and display the darker side of America, a nation coming off the heels of numerous political assassinations and presidential scandals. So how could an inspirational tale like Rocky be spiritually linked to a bleak psychological thriller like The Conversation or a gritty crime drama about alienated outcasts like Dog Day Afternoon? It may have been lost due to its franchising, but the story of Rocky Balboa (Stallone) is a true-blooded '70s film on its surface and deeper text.

'Rocky' in the Context of 1970s Cinema

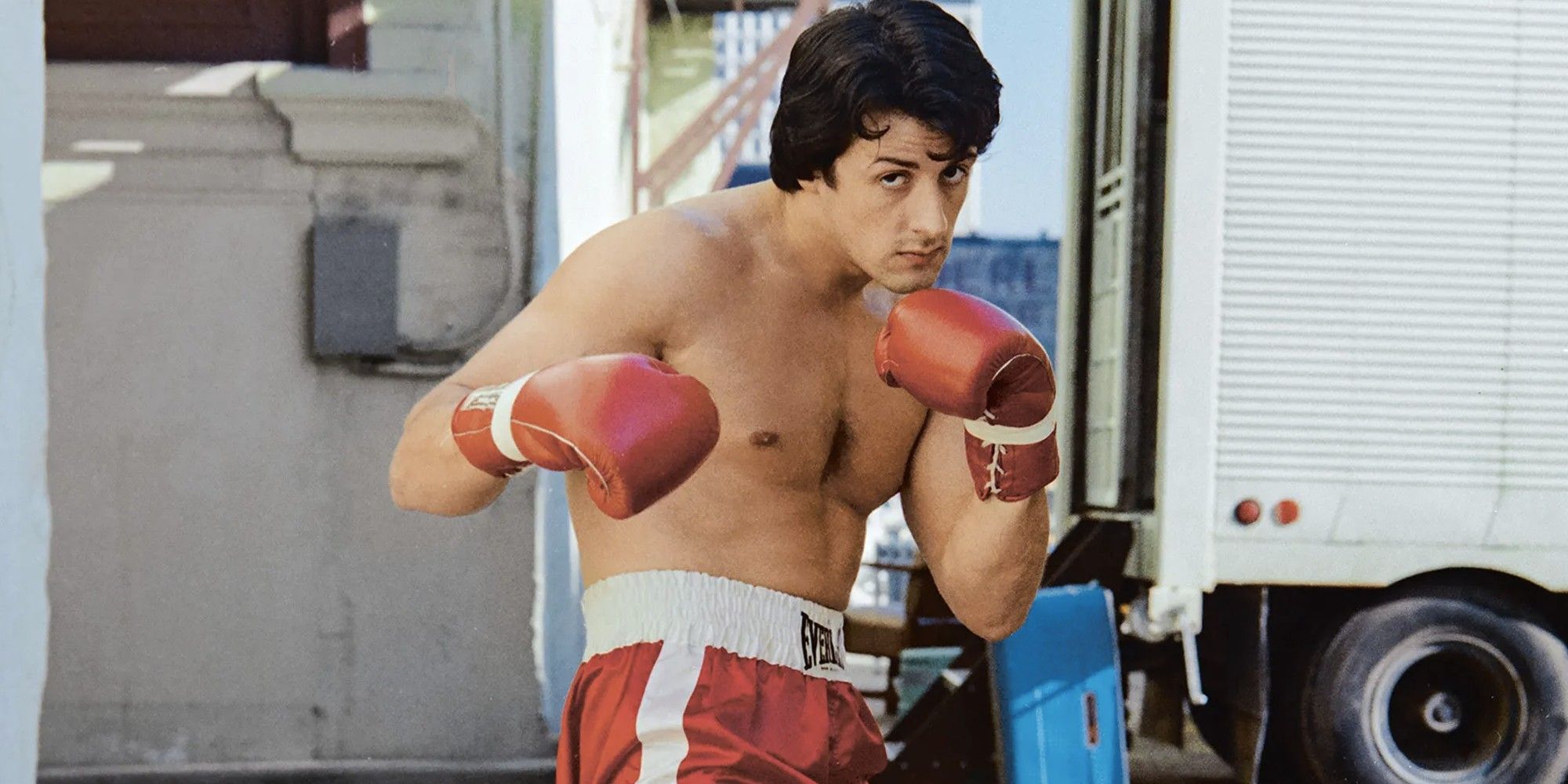

Director John G. Avildsen captured one of the most fundamental elements of a '70s picture: real locations. A previous credit of Avildsen, Joe, is a proper indicator of his New Hollywood sensibilities, with the film operating in retrospect like a trial run for Taxi Driver. While the expression has become clichéd, it is undeniable that the setting of Philadelphia is portrayed as a character in the same mold as the characterization of New York City in Mean Streets and The Taking of Pelham One Two Three. Rocky is immersive with its atmospheric urban location. The city's naturalistic background noises set the film's grounded tone and complement the humble beginnings of a loan shark enforcer and part-time boxer in Rocky. There is an aurora of decay encompassing the deemed city of brotherly love. Captivating shots of the city streets have the likening of a deserted wasteland. Taking the city where the founding of America occurred and displaying it at its most miserable was the expected practice in '70s filmmaking. The dreary streets and run-down building interiors create a pathos to the character of Rocky. He has a big heart but is ultimately oppressed by his setting. The film's version of Philadelphia is a constant reminder to him that, despite his steadfast benevolence, he will remain "just another bum from the neighborhood," as he confesses in a state of anxiety prior to his fight with champion Apollo Creed (Carl Weathers). His location may not drive him towards violent tendencies like Travis Bickle, but it will give him an everlasting sense of self-doubt.

The cast of characters in Rocky, while evergreen, are all born from the DNA of '70s Hollywood. Stallone is genuinely superb in his breakout role. The influence of Marlon Brando in On the Waterfront is unmistakable, and Brando himself was certainly impactful to the actors of this era. Adrian (Talia Shire) is a subversion of the traditional romantic female lead. She is timid to the point of being inhospitable, but like Rocky, the oppression of her living circumstances economically and from the emotional abuse she receives from her brother Paulie (Burt Young) weighs against her. In a slight deviation from most '70s movies, Paulie is only a supporting player, whereas, in most transgressive character studies of the time, he was the protagonist that you were meant to sympathize with. Despite being a friend of Rocky, he is bitter about the opportunity that he is given in fighting Apollo and the world at large. On the surface, Rocky's trainer, Mickey (Burgess Meredith), is nothing more than a hard-headed and grouchy motivator. He, too, is filled with remorse, regret, and the fearful realization that his life was wasted. The scene where Rocky and Mickey agree to work together for training is pure '70s. Inside a crummy apartment, they each reveal the bitterness they had towards each other, notably over how Rocky felt passed over by Mickey years prior.

The Thematic Subversions of the Underdog Story in 'Rocky'

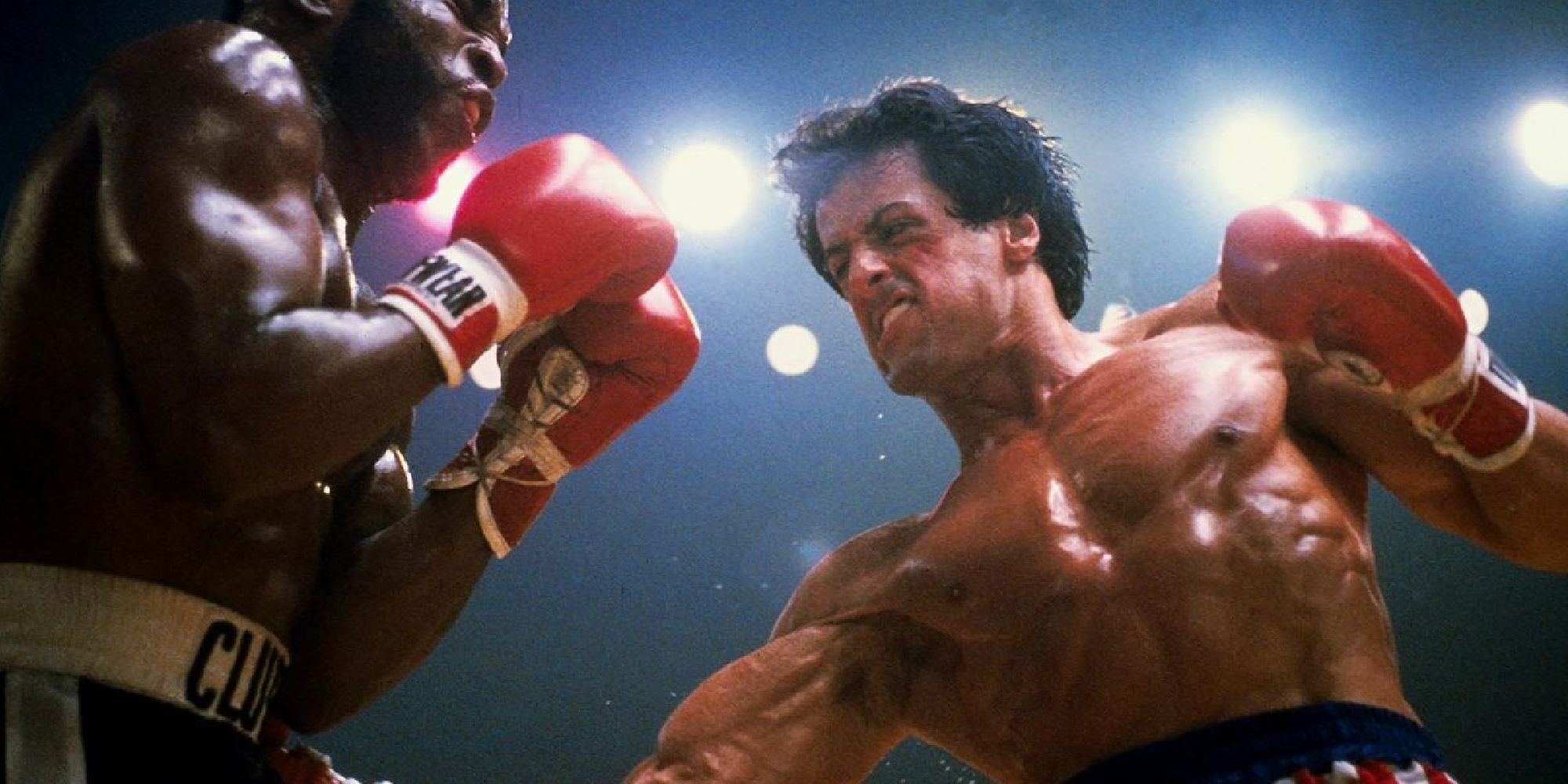

By the time the series evolved through the 1980s, Rocky was no longer about an everyday man struggling to get by, but rather a Herculean warrior fighting Russian cyborgs in a bout that impacted U.S.-Soviet relations in the Cold War. In the 1976 Avildsen film, Rocky is slighted by the removal of his gym locker. Even though he is outgoing and charismatic, he is apprehensive of the national spotlight surrounding his match with Apollo. The film's legacy, along with the entire franchise, will forever be remembered for the energizing training montage scored by Bill Conti's "Gonna Fly Now" that closes out with Rocky running up the steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Arts. This chilling moment of personal triumph has grown to define the series and the canon of sports movies in general, but a bold storytelling choice in the scene's aftermath separates Rocky from the rest of the pact.

Only in the '70s would the instance of the protagonist seemingly reaching a personal triumph be undercut by their own demons and insecurities. In a sobering confession to Adrian, Rocky is afraid to get in the ring against Apollo, certain that he can't win. Not only does Rocky's angst undermine the jubilation of the training montage, but the sheer reality of the situation. Harsh truths about the world pack a powerful punch in '70s cinema, as it is understood that Rocky is no match against Apollo. One of the most powerful images in the film comes when Rocky visits the ring the night before the fight and looks over the giant poster of himself that hangs in the air. He is left with a lingering discomfort after identifying that his poster shows him wearing the wrong color of shorts.

What 'Rocky' Said About America in the 1970s

For as grounded and contained as the narrative scope of Rocky is, there are numerous ideas about the working class and race relations in America, thematic elements that were prevalent among New Hollywood films, scattered throughout. For Rocky, boxing is pure labor just to make ends meet. In fact, his fighting style in the ring, solely through brute force and taking as many hits as possible to go the distance, is indicative of his blue-collar attitude towards the sport. The film also has a nuanced and precise interpretation of how the white working class seen in the film views a wealthy upper-class black person in Apollo Creed. There seems to be deep-seated animosity towards Apollo, notably with Paulie, for what he represents. He is viewed with animosity, as their prejudices lead them to believe that it is an injustice for a Black person to climb up the ladder of wealth and career status. It is a true testament to audiences of the time that this film became such a cultural landmark considering how the film is centered around fractured people with disjointed social and familial relationships. The only victories that the characters can strive for are minuscule in scale. For Paulie, it is to have his meat packing company advertised on Rocky's boxing robe. For Rocky, it is to just go the distance and not be an embarrassment.

As the final nod to the '70s cinema DNA that truly defines the original Rocky, audiences are given an irresolute ending, a staple of the perverse films of the era. On first viewing, one might not even know who won the match. While the call of Apollo's victory is muffled by the announcer, it is not important, because the fighter with a million-to-one shot went the distance. For New Hollywood standards, this ending is aggressively optimistic, but for inspirational underdog stories, accepting victory in defeat is quite profound.