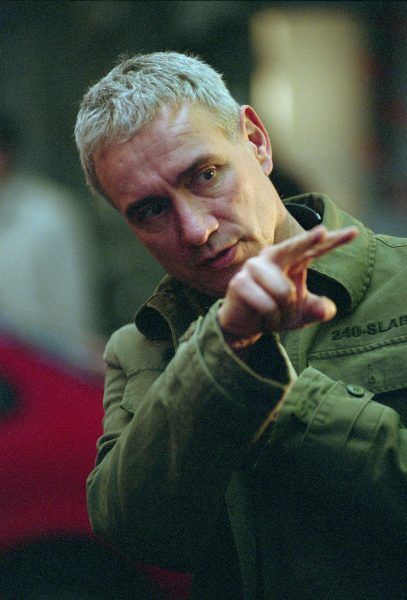

German-born filmmaker Roland Emmerich is sometimes referred to as “the master of disaster,” after directing a string of blockbuster disaster films like Independence Day, Godzilla, and The Day After Tomorrow, a global warming horror film released in 2004. The affable 63-year-old received a career tribute at The Zurich Film Festival, where The Day After Tomorrow was screened alongside several new films with a strong environmental message, including the Antarctic documentary Sanctuary, featuring Javier Bardem, and Watson, a film about eco-warrior Paul Watson directed by An Inconvenient Truth producer Lesley Chilcott.

Meanwhile, Emmerich’s new film, the World War II action-drama Midway, releases in November. It’s a familiar offer from Emmerich, featuring big-budget effects and an ensemble cast including Ed Skrein, Patrick Wilson, Luke Evans, Aaron Eckhart, and Nick Jonas. The film, about the American sailors and aviators who helped bring about the turning point in the war at the Battle of Midway, looks set to be a success story in the vein of The Patriot, Emmerich’s highly-praised 2000 Civil War drama starring Mel Gibson. Midway is mostly being kept under wraps, but Emmerich was happy to discuss how long it had been in the works. He also didn’t hold back on his battles with Hollywood and the serendipity that made his blockbusters a success.

An openly gay supporter of LGBTQ rights, Emmerich directed the 2015 movie Stonewall, about the 1969 Stonewall riots and the gay liberation movement. The drama showcases Emmerich’s for making smaller independent films as well as popcorn-fuelled blockbusters.

COLLIDER: Your father was a successful businessman making garden machinery in a small town outside of Stuttgart.

ROLAND EMMERICH: Early on I decided not to enter the family business and luckily I had two older brothers who were inclined to take over the company. So I got out of there really fast together with my sister.

You were more artistically inclined.

EMMERICH: I was always interested in painting, architecture and literature. When other kids were playing outside I was always reading a book. My mum would say to go out and get some fresh air and I’d say, “No, not today, maybe tomorrow”.

You were accepted to the Munich film school and initially wanted to be a production designer. Then you saw a movie that made you change your idea of what you could do with your life.

EMMERICH: I’d already been accepted to film school when I visited a friend studying fashion in Paris, and I was walking along the Champs Elysees and I saw a billboard for Close Encounters of the Third Kind. I watched the English version and from that moment something changed in me. I wasn't immediately saying I wanted to direct, but I wanted to be involved in movies like that. I was afraid of becoming a director because I had no idea how to do that, but I knew a little about the visual side.

What was it about the film?

EMMERICH: It was about very ordinary people. One is an electrician, one is a mother with a child and they are faced with something incredible, aliens coming to earth. This electrician ends up being one of the guys who goes up there with them.

A lot of your movies can be seen in a kind of Spielberg-ian style.

EMMERICH: Exactly. Pretty much my movies are about normal people facing incredible circumstances.

Your first film in film school was The Noah’s Ark Principle, which was crazily ambitious and shows how far you can go with virtually nothing.

EMMERICH: I don't want to watch it anymore! (Chuckles) I was with a group of students but they wanted to do something smaller and dropped out. I really only wanted to do the production design and I ended up being the director. In the beginning, the budget was 500,000 Deutsch Marks and we ended up spending 900,000 Marks and nearly bankrupted the film school. My father, who was better at business, enabled the film school to give us more funding, and he gave us 70,000 Marks for visual effects.

You started your company Centropolis with your sister Uta and made English-language films in Germany, Joey (Making Contact), Hollywood Monster (Ghost Chase) and Moon 44. How were they received?

EMMERICH: The Noah’s Ark Principle was very well received, then the others not so much. People couldn't understand someone making movies that look like American movies in Germany and the critics started trashing me more and more. Mario Kassar at Carolco wanted me to take over the reins of a Stallone movie budgeted at $65 million, so I went home to Stuttgart and said to my sister, “Pack up the office, we’re going to Hollywood.” They had lost Ridley Scott on the movie and he was one of my big heroes, so that was great for me.

Yet your first film was Universal Soldier and not the Stallone movie.

EMMERICH: It’s one of these typical stories about being a newcomer in Hollywood. I went to Cannes where James Cameron was there with T2 and everyone was asking, “Who is this Emmerich guy?” Joel Silver was the producer and I just didn't get along with him. He always wanted to tell me how to make a movie, and I said I know how to make movies. I was good friends with a young actor from Moon 44, Dean Devlin, and asked him, “Can we write a script for this movie?” We gave it to Carolco and they said it was so much better than they had. But Joel Silver refused to even read it and I knew I had to call it quits. I said to Mario, “This will cost $80 million and not be a good movie.” He was so impressed that he gave me a smaller movie.

That movie, Universal Soldier, ended up a success.

EMMERICH: Another director had to quit, as they couldn't make it for $35 million and Mario asked me if I could do it for $20 million and I said we’d have to write a new screenplay. I always have to invent stories myself, at least the initial idea. The only time I signed on to an existing screenplay was The Patriot. Mario was cool and said it’s about genetically-enhanced soldiers and it stars Jean-Claude Van Damme and Dolph Lundgren. I asked immediately, “Who is Jean-Claude Van Damme?” I rented all his videos and I went, “Ooh” and my co-writer Dean Devlin said, “You cannot work with these people”. And I said I have a great idea - we kill them at the beginning and when they wake up they are automatically-controlled people. (Laughs)

You were playing to their acting style essentially.

EMMERICH: Exactly!

Then you started to make original movies like Stargate.

EMMERICH: I already had the idea for Stargate in film school.

Was it difficult to pitch and get accepted?

EMMERICH: It was super hard to do. I went to every studio and the only person who said he could develop it was Lorenzo di Bonaventura at Warners, and he eventually went on to produce Transformers. He was a really nice guy. I said, “I want to make this movie now.” We found a young French producer Mark Friedman who had just started a production company owned by Canal Plus who had a huge stake in Carolco. They said, “How much do you need?” I said $35 million and he said, “Let’s do it.” The movie was made without American distribution and when we’d finished it and it had great visuals Mario screened a reel to everybody. I later learned he wanted to make an overall deal with MGM, so they got it, and at the time having your film at MGM was pretty much the death knell of your career. But we knew how to market it. Dean was very computer savvy. He created the first web page ever for a movie and that reached so many people. MGM marketed the movie for young boys, and in the end, 75% of our audience was over 25. But it was very successful and was called a sleeper hit. It was the biggest October opening for 10 years or so, and that naturally brought a lot of interest.

Afterward, you made the film that launched your career - Independence Day, which you also wrote and produced. You got it going quickly and it became the template for how you would make movies.

EMMERICH: After Stargate I went to a new agent who had all the big writers like Shane Black and Joe Eszterhas. I always wanted to make big alien invasion movies but I first had to convince Dean and finally did. Then I learned from Lorenzo there was another movie called Mars Attacks! with Tim Burton, one of my favorite directors. I knew a bit about Mars Attacks! and every one said to give up. I said, “No let’s go to Mexico and lock ourselves in a room” and in three and a half weeks we wrote Independence Day. My agent asked if I could put a number to it and we auctioned it like we auctioned my scripts, which had never been done before. We came in with a budget of $73 million and they offered $69.8 million. Then we went to the whole town wondering how we could release before Mars Attacks! which was scheduled for August. I said, “Let’s call it Independence Day, let’s have it take place on Independence Day and insist on the 4th July weekend”. That was our condition and every studio wanted to make it and it ended up at Fox. Tim Burton was already shooting and we wrote, shot and finished it in 10 to 11 months.

The film became the fastest to reach $100 million in the US. It was a monster success globally. How did that change your life?

EMMERICH: I naturally got the biggest movie that everyone wanted to do which was Godzilla. I didn't want to do it, but because I didn't want to do it they went higher and higher with the salary and the backend got bigger and bigger. But I said I would not make Godzilla look like Godzilla. We made him look like a lizard and went with [an image of] this thing to Tokyo where the same company had Independence Day, which had been a sensation and they felt compelled to make my next movie. But when we revealed it to them they said you make your American Godzilla and we’ll make our own Godzilla. I said, “Fine with me”. But I was a bit disappointed because I thought, “Shit, now I have to do this thing!”

Do you have any regrets about making Godzilla?

EMMERICH: A little bit. It did all right commercially, but I’ve always said monster films have a limit. Later Peter Jackson did King Kong and it roughly did the same money as Godzilla. Everyone said it would make the same money as Independence Day and I said, “No, it will make half the money” and that’s exactly what it did. Who would go to a Japanese monster movie? It’s a certain kind of audience and that was that.

Afterward, you made The Patriot, a very different American story.

EMMERICH: I wanted to do Midway and at that time John Caillie had just been made chairman at Sony and he made this huge deal with Dean and me. I pitched Midway as this amazing story, “It’s perfect everything is there.” He said, “Oh my God, a great idea. Who do you want to write it?” I said William Goldman. He said, “I know him, I can call him.” He was at that time the biggest screenwriter in Hollywood, even if he lived in New York, and I ended sitting with Dean in his living room and told him that he also wrote A Bridge Too Far and he immediately said, “Great, let’s do it.” Then I had bad news from John Caillie. “Can you make this movie for under $100 million?” I said, “No, its $120 or $130 million because of the visual effects. Nobody’s ever done something like that.” So he couldn't greenlight the film for more than $90 million. I was super depressed, then Chris Lee, a friend running Tristar, said, “Don't worry, I just got a great script in turnaround by the same guy who wrote Saving Private Ryan (Robert Rodat) and that was The Patriot.

Were you worried about making a historical American story as a German?

EMMERICH: It was a fantastic script. When I signed on I was made to believe it was about Francis Marion so I read every book about him. In the script he had seven children, but in real life, he had one child. Then I realized it wouldn't be about him and would be a composite figure because there were four or five guys who became these famous rebels--as opposed to the army--and they called themselves patriots.

You’ve always been a political person personally, but it’s not something that showed up in your movies. But after that, you did The Day After Tomorrow, a film with a strong environmental message that was very unique at the time.

EMMERICH: I had to kind of trick Hollywood to make this movie, because I said to myself and said to them what I said to my friends and my sister when they asked me what I was doing next, and I said a film about global warming. They said, “What?” I wanted to do something about climate change and I came across a book called The Coming of the Global Superstorm written by Whitley Strieber and Art Bell who had this crazy radio show, and Strieber wrote Communion where he thinks he got abducted by aliens. I recently acquired another of his books and he told me he has a brain implant. He’s that kind of guy. So it was a great idea where one superstorm brings on a new Ice Age. When you think about global warming, anything can happen with climate change. You might radically tell it, but the underlying science was totally real. So I acquired the rights and changed the title and wrote it a bit in the style of Independence Day. Everyone wanted a new Independence Day. It was called The Day After Tomorrow and they weren’t so happy about the title, but there was this feeding frenzy going on and I could make the film.

You campaigned for Hilary Clinton, you are a big supporter of LGBTQ rights, and gave a large donation to Outfest for their Legacy Project for the preservation of gay and lesbian films. Why did you want to make that contribution to preserve those films?

EMMERICH: I really believe that movies have to say something. It doesn't matter what it is. Even with successful movies like Independence Day, everyone knows what it means to be invaded when things come and destroy your life, and it’s about your fight for freedom. I think that's a universal theme. I became very concerned about the environment and I had the feeling I had to do something about it and came up with that. Then you have to be smart in the way you do it. I was recently asked by a journalist why I think there are no environmental movies anymore and I said, “Well, there aren’t any original movies anymore, but if you invent like a superhero who fights climate change, maybe then you can do it.”

You’re political but you’re not perceived that way.

EMMERICH: Yes. They always think I’m Right Wing or something. People love to put people in a box and say that this is what you are. I had three movies that did really well, Independence Day, Godzilla, and The Day After Tomorrow, which were all about destruction and they think you’re the master of disaster. What will you destroy next?

Midway is about to come out. You didn't go the typical route of going to a studio and getting them to pay for it. You financed it in the independent market.

EMMERICH: I was forced to do it that way. I went to every studio, and at that stage, the movie had a much bigger budget of $125 million, and they said it’s too expensive. Then our agents and other people said maybe we go to the independent market, maybe to China, and that’s what we did. Roeg Sutherland went out and looked for Chinese money and there was huge interest. We went to Cannes and someone could pay $80 million, but I needed $20 million more. So they said you can keep the US market and it was stop, go, stop, go, stop, go. I have the feeling that's the future for directors of my kind because studios aren’t so inclined anymore to risk anything. With movies costing more than $50-60 million, you have to take a risk because you have to pay $35 million for print and advertising on top of your budget. Then they’re looking at every war movie ever made and they realize only three movies made enough money to make their budgets back, so they naturally decided against it. It was tough, but we pulled through it and we’re very proud of the film.

Is that the biggest shift now, going to the independent market to get finance?

EMMERICH: The most successful film in the last year was Avengers: Endgame, and I heard the Russo brothers wanted to do the original movie for $50/60 million, and they had a tough time getting it financed. It made $2.8 billion. It doesn't matter for Hollywood how much because they don't think it’s these guys doing it. It’s Marvel, it’s Kevin Feige, it’s this whole big apparatus who make these films.

The Day After Tomorrow was the first Hollywood film about carbon emissions based on calculations from a UCLA study. How do you deal with it [carbon emissions] when you make movies?

EMMERICH: To pay for carbon emissions is a good thing, but it won’t change much. I think we all have to become vegetarians, to figure out how not to use oil, there are a lot of things we have to do. When you see how big the problem is, there are solutions. I’m actually really pessimistic. The first time I was a bit optimistic was when kids all over the world led by a 16-year-old girl from Sweden [Greta Thunberg] started going on the streets and she recently spoke in front of the UN. I think the future generation sees the problem as so big that they want to tell everybody. But politicians don't really care.

Do you have any tips for young filmmakers?

EMMERICH: The industry has changed since I first went to Hollywood. They wanted creativity, now it's the opposite. I’ve found it was more important the things I said no to as opposed to the things I said yes to. It’s much more important that you know what you want than what other people want you to do.

There’s a period now when Hollywood wants prequels and sequels. Why and how will it change?

EMMERICH: Hollywood is always changing. If you don't change with it you become a dinosaur. I hope it will change again because I don’t think the quality of movies we are making are as good as maybe in the 70s, 80s, and 90s, even 10 years ago. Every once in a while good movies are made, but now big movies often only work because a hero has some funny dress or can fly. It's a little depressing but in the end, you have to go with your times. I hope it will change again but I’m not so sure. You can never predict the future, it would be great, so you just have to concentrate on what you’re doing and hope people out in the world want to see it.

What more can you tell us about Midway?

EMMERICH: As I said, I wanted to do Midway for 20 years and I’m super excited about that story. When you analyze it, it’s a simple story and it’s good that I didn't do it then because people aren’t as sensitive as they are now, because it tells of people holding off fascism and it was exactly seen then like that. When you see how nationalism played against globalism - I’m a globalist, I think everyone should work together and nations are a thing of the past. But now it’s exactly the opposite. There are demagogues who tell people to be nationalistic and everything will be better, but nationalism created World War II. So I think it's a good story to tell today.

Do you believe in aliens?

EMMERICH: I get asked that question a lot. I have to say I wish there were aliens, because it’s such a great story and you can make so many different stories. I think aliens have taken over from fairies and other fable-like creatures. I also believe that Hollywood isn’t doing a good job these days in educating the world. I think they’re doing exactly the opposite. They’re telling kids that superheroes exist, and they don't exist. In a disaster movie, normal regular people have to become heroes and not superheroes.

Which actors have you liked working with?

EMMERICH: I’ve always liked and really admired Mel Gibson; he was always on the set of The Patriot every day and was the easiest actor I’ve worked with. In Anonymous, which was more an ensemble, I worked with a lot of great actors coming from the theatre like Vanessa Redgrave and Rhys Ifans and it was probably the best time of my life. It was the first time working with people where it wasn't just about the acting but also about the storytelling and what the scene has to tell you.

After disaster movies and historical movies, what movies do you want to make?

EMMERICH: I wrote a script 20 years ago and recently rewrote it extensively. It’s called Shooting Star and is a very comedic movie but also delves into a movie shoot taking place in the Californian desert in 1919, 1920 or 1921. It’s about filmmaking. That’s probably closest to my heart these days and I know I have to do one or two other movies beforehand, but I’m looking forward to doing that.