Today we found out that Ron Cobb, the highly influential concept designer and art director, died in Sydney, Australia. It was his birthday. He was 83. But the legacy he leaves behind is truly staggering – and even if you never knew his name, chances are you were touched by his work. His draftsmanship is intricate but never unidentifiable; you always knew a Ron Cobb design when you saw one, defined by clean lines and a kind of bulky, lived-in aesthetic that made you believe that things like spaceships and giant robots and memory machines were actually real.

Cobb was born in Los Angeles and began his professional life in the mid-1950s working at Walt Disney’s animation studio, first as an “in-betweener” and later as a breakdown artist on Sleeping Beauty. After Sleeping Beauty’s lengthy and expensive production gave way to a dismal box office performance, Cobb (along with many others) were laid off from the studio. He was drafted into the Vietnam War and, upon his return, began to do freelance illustrations (most notably he designed the cover to Jefferson Airplane’s LSD-indebted After Bathing at Baxter’s). In the late 60s/early 70s, he contributed designs to John Carpenter’s debut Dark Star, which began life as a student film and wound up a theatrical presentation. It was on the film that Cobb would connect with squirrely writer Dan O’Bannon, which would lead to two of his highest profile jobs – the infamous, aborted adaptation of Dune by Chilean filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky and Ridley Scott’s Alien.

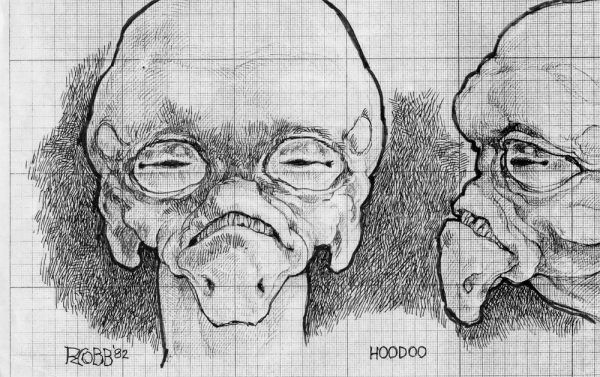

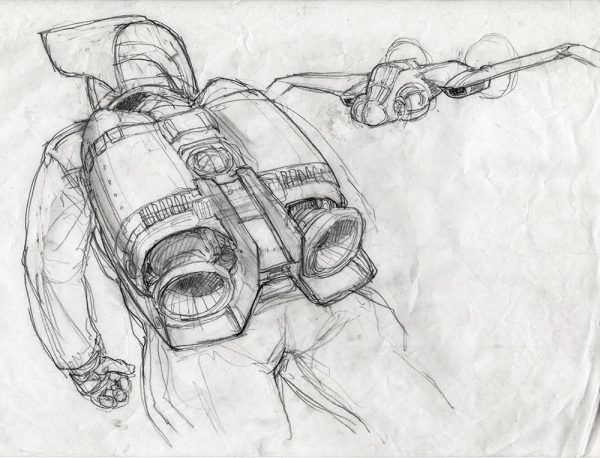

Starting in 1977, with uncredited work on George Lucas’ Star Wars (he added a number of unforgettable aliens to the Mos Eisley Cantina sequence), Cobb’s contributions to science-fiction and fantasy films of the 1970s and 1980s is nearly unparalleled. (The closest comparison is his colleague Syd Mead, who offered similarly distinct designs to a number of influential films and who passed away late last year; he was only three years older than Cobb.) Cobb designed (amongst other things) the inside and outside of the Nostromo ship in Alien (he also took a crack at the derelict craft, the space jockey and the alien itself, all of which wound up being designed by his fellow Dune collaborator H.R. Giger); pioneering that film's breakthrough "used future" aethetic. Cobb also did the “flying wing” airplane in Raiders of the Lost Ark; and designed all of Conan the Barbarian (he also shot second unit). He also designed The Last Starfighter and worked on a number of the film’s then-cutting-edge computer-generated effects; came back for James Cameron’s Aliens; designed the DeLorean in Back to the Future and did the indelible title treatment for Steven Spielberg’s Amazing Stories anthology series. Other 80s classics he worked on: Real Genius, The Running Man, Robot Jox, Leviathan, The Abyss and the ahead-of-its-time ZZ Top video for “Rough Boy.” He was, in a word, unstoppable.

But just as fascinating as what he worked on were the things that didn’t make it through. Most famously, while working on Raiders of the Lost Ark, Spielberg asked him to direct the follow-up to Close Encounters of the Third Kind for Columbia. (Cobb had contributed to the "special edition" of Close Encounters as well.) This time, Spielberg wanted to dramatize one of the most famous examples of a “close encounter” – the Kelly-Hopkinsville Incident, in which a family in rural Kentucky was supposedly terrorized by a band of menacing extraterrestrials. (Project Blue Book, the US government’s official probe into the phenomena, labeled it a hoax.) Cobb assembled a crack team that included screenwriter John Sayles and make-up effects wizard Rick Baker. While working on Conan, Cobb flew to Paris and pitched Spielberg. By this point, the story had shifted to avoid a lawsuit from the family involved in the initial incident, and ultimately the ballooning budget would capsize the project. The band of aliens was whittled down to a single alien, and the storyline for this new project was distilled from the ending of Cobb’s – a solitary alien, left alone on earth.

“Then the rumors started coming. I realized that Steven had changed the script a lot. He went back to a story he had told me about years before: An alien is abandoned and protected by a little boy. It wasn’t scary anymore. It was kind of sweet,” Cobb told the Los Angeles Times in 1988. Cobb got to have a cameo in the film as one of the scary scientists observing the dying alien. While the designer didn’t care much for the final film, now called E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (“sentimental and self-indulgent”), he did look into the fine print of his contract, which stated that he would get a $7,500 kill fee and 1% of the profits, should the film be made by another filmmaker. He fired off a letter to Universal on a whim. He didn’t expect to hear anything. He got a check back for $400,000. The checks kept coming.

He worked on a proposed western called Half the Sky, and an American miniseries version of Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy (he and Douglas Adams became friends) and sold a sci-fi comedy to Warner Bros. called Atoll. But the most insane and potentially the most important project he worked on that never saw the light of day was something he referred to as Mars-1. In his L.A. Times profile, they describe it as “an inspirational short film promoting world peace through a joint Soviet-American mission to Mars.” On his official website, the designer described it as a joint project between MCA, Apple Computers and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Cobb co-wrote the script and designed the spacecraft and the project fell apart when the Soviet Union crumbled. Truly insane.

Just as an aside, towards the end of the 1980s Cobb was also designed dinosaurs on something described by the L.A. Times in frustratingly vague terms as a “proposed time-travel tour at Disney’s Florida studios.” This could have been a redo of the EPCOT Center pavilion Universe of Energy, which notably featured dinosaurs, or it could have been for what would eventually become Countdown to Extinction (later renamed Dinosaur), which saw guests traveling back to prehistoric times to rescue a dinosaur. (Another master illustrator, William Stout, contributed to that eventual project.)

Throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s he would continue to contribute memorably to cinema – everything from designing pretty much every machine in Total Recall to defining the look of the bombs in True Lies to the rocket pack in The Rocketeer to somehow creating unique and wildly different spaceships for projects as varied as Space Truckers, Firefly, Titan A.E., Southland Tales (all hail the Mega-Zeppelin), and The 6th Day. (He also did an unused take on the aliens from District 9.) Additionally in the early 1990s he also managed to direct a low-budget comedy in Australia called Garbo.

Fittingly, one of the last projects he worked on was a Disney film – Andrew Stanton’s John Carter. He proposed the look of several alien species and spaceships and his work went uncredited. Tellingly, they’re more creative and eye-popping than anything that wound up in the actual movie. After all, an important part of his legacy is all of the incredible work that nobody got to see finalized.