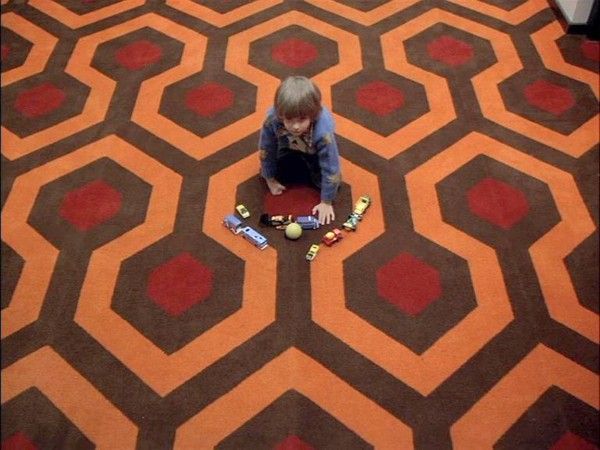

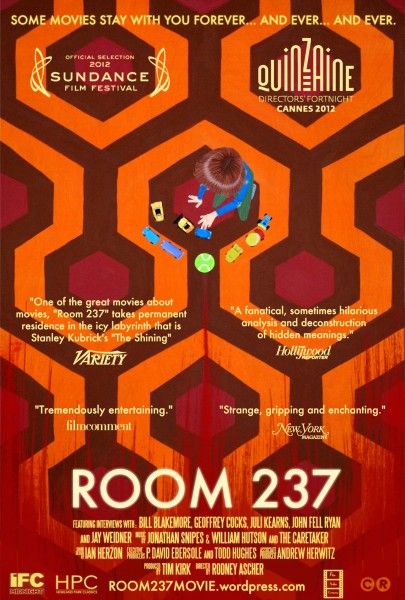

It’s been over three decades since Stanley Kubrick released his classic horror film, The Shining, and viewers are still struggling to decipher its hidden meanings. In an entertaining deconstruction of one of the greatest horror movies of all time, Room 237 interviews five fans and scholars who each have wildly different theories. All are convinced they have decoded secret messages covering topics as disparate as Native Americans, Marshall McCluhan, genocide, government conspiracy, numerology, synchronicity, World War II and more.

At the recent press day, director Rodney Ascher and producer Tim Kirk talked about why The Shining continues to fascinate people, how Kubrick seemed to put everything in for a reason, how they see it as a puzzle that’s missing a few pieces, why they focused on the reactions of the audience and the way they put the pieces together rather than doing a behind-the-scenes style documentary, how they were surprised to find more connections than contradictions after combing through many hours of footage, the two big interviews that got away, why they’re interested in Stephen King’s reaction, and why there’s so much more that could be said including their own theories about The Shining. Hit the jump to read more.

Question: It’s been over 30 years since Kubrick made The Shining. What is it about this film that continues to fascinate people and generate so many theories about what it means?

Rodney Ascher: I think a big part of it is that The Shining is really a puzzle that’s missing a few pieces. Even at the simplest level of story, there are huge gaps in what we know about what goes on in it. The central event in the film, what happens to Danny in Room 237, is never explained, let alone shown. That black and white photo at the end of it was presented as if it was the answer to some kind of puzzle that we had all along, but if anything, it’s an entirely new question about what’s happening in the film. I think people are attracted to watch it and re-watch it to try to solve those sorts of puzzles, and then they find all these new ones. A lot of our movies end by giving you the shock answer of what happens that explains everything, and in a way, you can leave satisfied. Shutter Island is a really interesting movie, but the twist ending in that movie puts everything into perspective and you kind of get it. With The Shining, you never quite get it. It’s troubling because it seems on the surface a very simple story of three people in a hotel over the winter and they start to see ghosts, and trying to find the point where it kind of breaks up is endlessly complicated. It’s also a horror movie that’s a fun, entertaining film, so people watch it just because they want to watch it and not like it’s a homework assignment, like a more difficult, challenging art film might be. When they find things that don’t add up, they’re compelled to re-watch it.

This was such a departure from what Kubrick had done previously, and also, he’s linking up with Stephen King who was this popular novelist. Do you think people are trying to figure out why he would do this?

Tim Kirk: I think so, and people who are familiar with Kubrick and his other films are interested to see him do a take on that kind of film in a new genre. And then, just because he was known to be so meticulous and such a perfectionist in the multiple takes and so forth, there’s this feeling that if there’s anything in the frame, he put it there and there’s a reason, and that reason can be determined.

Ascher: And if you don’t understand something, it’s not his mistake. It’s your problem.

Have you had a reaction from Stephen King to Room 237?

Ascher: Not yet. But he’s one of the people I’m most interested to get a reaction because in some ways you can see this as a game of telephone, and he’s the one who started.

In the film, someone says Kubrick had an IQ of 200 which is past genius. How did you find out about that?

Kirk: That’s actually Jay Weidner, the person we interviewed, saying that. Fact checking wasn’t a major part of our film, and I mean that in a positive way.

Ascher: This is not a hard core behind-the-scenes film. This is what are people saying about The Shining? How are they struggling to make sense of this problem that’s been dumped in their lap?

Kirk: That leads to a bigger point, which is, Rodney and I in discussing how this film would be and what it might be like before we interviewed anyone, one of the decisions was that we weren’t going to talk to people that worked on the film, that it wasn’t going to be a behind-the-scenes or here’s the answer. As much as Rodney and Tim would love to know that, that didn’t seem appropriate as the filmmakers [inaudible].

He puts things in there for a reason because he wants to catch your eye, and that seems to come across in all of his films since Paths of Glory where you have that long shot of the battle that just keeps going.

Ascher: That’s amazing.

The Killing is another one with the mixed up time periods.

Ascher: Those are very unusual choices made at a pretty early time. I mean, a film noir with that scrambled chronology is a pretty radical choice. And I hear actually at one point they had worked on a cut of taking that out, but somehow they came to their senses and said, “Let’s leave it this more complicated way.” Certainly, with the partial exception of Spartacus, he’s always been a filmmaker who’s done things exactly to his own vision. So, there is more reason to assume that unusual choices and small details in a Kubrick film are more intentional than you might assume with another filmmaker.

There are so many different conspiracy theories that you guys delve into. Some of them make complete sense while others are completely outlandish, like seeing Kubrick in the clouds or the paper tray erection.

Ascher: But you can totally see that. (laughs) It is clear as a bell.

I just wonder how many times he watched that before he said, “Yes, it’s there!” What is the most outlandish or over the top thing that you did here?

Ascher: That The Shining is the story of three people trapped in a hotel over the winter and they see ghosts.

Was there anything you rejected because it was too outlandish?

Kirk: There were people we wanted to interview that we couldn’t for one reason or another, like two big fish that got away. But I don’t think outlandish was ever a yardstick. I think it was more if it was less persuasive or didn’t grab us in some way or another.

Ascher: Outlandish is a hard thing to dismiss when you’re talking about a symbolic interpretation of a horror movie that’s drawing on things like Freud’s sense of the uncanny.

Once you guys developed these five main theories that drive the film, why did you only have one voice represent them instead of a compilation of people who also support them?

Ascher: It was about wanting to dive deeper down fewer holes and not assemble something that’s a thousand sound bytes, but to let someone take the time to lay the groundwork and expand on it. There was somebody who actually had something negative to say about the film, but I took it as a compliment, comparing it to a late night dorm room conversation. I remember really loving those conversations where it’s like, “I have a class at 8 in the morning, but we haven’t quite figured out the implications of this song or Dawn of the Dead yet. So, although it’s 3 in the morning, we’re going to take another look and dive deeper in there. It’s that excitement that’s kind of contagious. I wanted to spend more time with these folks and let them go further, and in a way go deeper down each of these five holes than cover it with a lot of others.

Kirk: There was a point in the research of this where we were going to give it a more comprehensive view of every theory that is out there, but it became clear that it was just insane. I do have the spreadsheet that was an attempt to have each one and where they overlapped and all the different people that I could talk to that would complement or disagree on these various things. But ultimately, once we started interviewing a few people, these guys were so compelling and so engaged in the material, [we decided] let’s let them talk. Let’s try and be as persuasive on behalf of them as we can.

What was your thinking behind not showing their faces?

Ascher: It was a style that I started with a short film that I had done a year or two earlier which worked in some interesting and unexpected ways. I may have started it in that project because it was a no budget, personal 10-minute film, but it did a lot of things that I was really interested in, not the least of which was when I didn’t have a talking head shot to go back to, I would have to struggle harder to find imagery to illustrate these ideas. Sometimes it would be very, very literal, but other times it would open up the door to using something subjectively that would be kind of interesting and would stretch the original intention of the footage in a cool way. I think also stylistically sometimes when you see the talking head shot, it’s like coming up for breath or coming down for a landing and it’s like, “Okay, now we’re back in reality and then we’re going to go into the montage.” I just wanted to stay in that dreamlike world of ideas and pictures and let the movie take place in outer space and the Old West and not somebody’s office or a hotel room or living room.

How hard was it for you to gain access to all of the imagery and acquire the rights to use it?

Ascher: It took a while.

Kirk: It was a complicated process, but I’m proud of it. When Rodney was cutting the film, some of these issues would come up, and I’d go, “Cut it the way you want it, and then we’ll see what we can do.” As part of the clearance process, we had to change some things. We had to tweak some things. We had to go to certain links to get the clearance, but in the end, I feel like the film that’s going to be shown in theaters is very close to Rodney’s initial vision.

Who was the person who wouldn’t talk to you that you mentioned at the end of the film?

Ascher: He was identified on screen as The Mastermind. He’s amazing. He was one of the big fish that got away. The other might be this British guy, Rob Ager, who’s got a website called Collative Learning which goes deep into The Shining and other films. He’s kind of intimidating. I talked to him on the phone for about 25 minutes and just felt like an idiot because his vocabulary was so far beyond mine. I don’t know a whole lot about him personally, but he seems like an academic guy, maybe someone at MIT with that kind of background. I could mostly understand what he said, but if I tried to come up with a follow-up question, I felt incredibly self-conscious and like a big dummy. His site, which talks about The Shining, is an amazing, mind-blowing thing where he describes it in some ways…and I’m not going to do any sort of justice to his thoughts, but it’s something about how The Shining is working to compare and contrast the power of pictures over the picture of words and demonstrate their superiority in a way that draws on Marshall McLuhan and folks.

So, in a lot of ways, I was very disappointed that we weren’t able to get him, but again, there was a moment early in the making of this film when we realized what we were going to be able to present was only the tip of the iceberg. There’s that moment when it says he didn’t want to appear or we see webpages of other people who have written other things about The Shining that try to suggest that. In a way, I think that maybe makes this project [open ended]. There’s something interesting about that, because when you hear that this is a 104-minute exercise in studying the symbolic layers of The Shining, you might think, “Man, they really had to have stretched it to fill up that much time.” It was actually the opposite and this thing could have been 10-1/2 hours and kept going. Whenever we had a chance, we gave an indication that, “You think there’s a lot here, but look over the cliff.” It just goes forever and that’s an interesting idea to wrestle with.

Given Kubrick’s high IQ and sophistication as a filmmaker and The Mastermind’s obvious intellect, do you think he might have recognized a kindred soul?

Ascher: I think almost everyone we talked to, and us too, would recognize a kinship with something that Kubrick has done, and that we all focus in on different areas. I was especially interested in his editing process, in thinking about the way he scrambled chronology going back as far as The Killing, and certainly that scene in 2001 where the caveman is looking at the monolith and you see flash forwards of those wild boars getting knocked down. Is that the idea or is that the ramification? And what time are we looking at? Or is that scene with the monolith a flashback? That also informed the way I looked at The Shining and wondering how much of it is skipping through time. Even things like when you see the ghosts, is that a weird sort of flashback where you’re seeing what’s happening in the hotel earlier, or is that edited out of sequence? Since I was teaching an editing class at that time, I would see Kubrick as really one of the most accomplished film editors in the way that he used film editing language. But our composer said, “That’s really weird because I think of him as the ultimate music supervisor.” If you think of the choices of music that he’s made in his films, they’ve both been so powerful and so influential. Using The Blue Danube over the spaceships circling in 2001 is an incredibly bold choice rather than some kind of generic science fiction soundtrack. So, I’m sure the Mastermind, Kevin, recognized a kindred soul in him and so do people that we talk about.

Kirk: On the intelligence thing, there was one point fairly early on when I realized that almost everyone we were interviewing thought of Kubrick as just a little bit smarter than them. Bill Blakemore has spent his life reporting on genocide and struggling with why this keeps happening in our world. And so, he thinks that Kubrick would have struggled with the same things, but maybe Kubrick had an answer. And Jay Weidner thinks that Kubrick would have faked this Moon landing, but he can see those clues.

Ascher: Jay Weidner says flat out that watching 2001 as a kid inspired him to become a filmmaker. He talks about Kubrick in our film, but if you go to his website, you’ll see he’s made two of his own Kubrick DVDs with a third coming out. But he’s also made a ton of his own documentaries and film projects, and Kubrick launched him down that path.

Is there a tendency to see Kubrick as infallible when some of the things that were highlighted in the movie could be due to continuity errors given the convoluted and lengthy production process of the actual movie?

Kirk: For sure, there is a tendency to think of him as infallible.

Ascher: But he does have a pretty good track record going into The Shining. He did have more personal control over the details of his films than other folks. You’re not the first person to suggest that some of those continuity issues might have just been errors, but there sure were a lot of them. If some of them were, I can’t believe all of them were. Coming from one of the most accomplished filmmakers of all time, if you see something that looks like an accident at first glimpse, there’s at least a reason to go and consider it and say, “Is that really an accident?”

Or how many of those are happy accidents and he just guided the mistakes in a way?

Ascher: Well, I studied a little bit of improv, and there’s a whole philosophy about working with accidents.

Wendy Carlos, the composer of the soundtrack for The Shining, said she felt like a complete failure because she had to mix in all kinds of other music. How do you feel about the music in The Shining?

Ascher: I loved the music in The Shining and I think Wendy Carlos’ theme song at the beginning, her version of Dies Irae (Day of Wrath), is what scared me out of the theater when I was a little kid. What’s really interesting is that there are lots of people who search for things that are in the book that are only slightly in the movie. I hear bees in her music for The Shining, and there’s a big bee sequence in the book that didn’t make it into the movie, but they’re there through her soundtrack. I think he might have done the same thing to her that he did in 2001, which was to replace a lot of her specially composed music for stuff from his record collection. This is something that happens to directors all the time, that while they’re waiting for the composer, they use music that they happen to have and they fall in love with it. But he also has a way of transforming it and using music in interesting, kind of opposite ways. We weren’t able to get into it much in 237, but in The Shining there are things, and Geoffrey Cocks, in particular, talks about the history of some of the composers who worked on the music. I think Bartok had some run-ins with the Nazis back when he lived in Germany, and it was significant that the version of the recording that he used was from a German orchestra. He talks about another selection of music called The Dream of Jacob which ties us into Old Testament readings of the movie. But I loved the music in The Shining, and he might have put her through hell in order to get what he needed, but he did the same thing to Shelley Duvall. He might have shaken her up, but she’s amazing in the movie.

Do you think your film at some point might be dissected the same way?

Kirk: I hope so. It’s interesting. I have a 5-year-old daughter, and she’s very interested in what I’m doing, so she really wants to see The Shining and that’s not going to happen. But some day she will, and she’ll see it in a world where Room 237 exists, and she knows that people think about this including her dad. I just can’t get into my head that second generation or third generation viewing of The Shining or Room 237.

If another documentarian who was making another movie about The Shining was to interview you and asked you to pick one theory you liked, which one would it be?

Ascher: I think I might use the one that’s more personal to me. Tim and I have talked about it and it kind of works on both of us. It’s what the movie says about family and as sort of a cautionary tale about how people can let their work and things tear their family apart or blame their failures on them and not let that happen. The ghosts in the hotel can represent some of the temptations out there that might lead you to betray your family, like you might rather be in a fancy hotel room talking to journalists about your film instead of staying home taking care of your baby, and that you should try to resist that temptation nonetheless.

With all of the conspiracy theories out there, the research that you’ve done, and everyone that you’ve interviewed, what was the one thing that somebody said that really stuck with you or maybe opened your eyes to a whole new set of theories?

Kirk: First of all, I could listen to Bill Blakemore talk for 8 hours straight. He’s a really compelling guy. But there was one. I remember reading Jay’s essay early in the process and being maybe a little dismissive about the moon landing thing. And then, I got to this part where he was talking about if Jack (Nicholson) represents the caretaker of the hotel for the Apollo missions, the previous caretaker would be representing the previous program from NASA and it was Gemini, which are twins, and Grady (Philip Stones) had twins. I just remember my hand shaking. Oh my God! I had a couple of those kind of moments during this film, but that one still stands out to me as the one where I kind of left my body for a little while.

Ascher: It’s that thing where if these were term papers, you’ve got the topic sentence or the thesis statement which is placed in overview. As the points pile up, they get more and more persuasive, and maybe it’s the third, fourth or fifth point, but at a certain level it becomes totally persuasive. One thing that was really interesting to me and made me want to re-watch the movie again and pay attention to a very particular thread was John Fell Ryan talking about the power of the dissolves and how they work to transition between two scenes and wasn’t just a way to span time, but that intermediary space between them would create a relationship that was meaningful and was saying something in particular. At one point, he saw those two pictures of Jack Nicholson come together and form the Hitler mustache, which is amazing, because I had seen that shot a hundred times but I was never capable of seeing that image. What was especially eerie about that was it reinforced Geoffrey Cocks’ story about how there were two themes in the film. Arguably, these guys are coming from different worlds. And then, when I watched the film again, paying attention to the dissolves, I don’t know if the things that I found were things other than what John Fell Ryan found, but these are things that I didn’t talk to him about or I didn’t recall him reading, and I would find more of those relationships. There’s the simple visual of the cars coming around the mountain, and then, as the dissolve comes to the parking lot of the hotel, it’s like the road is leading straight into the hotel from two different vantage points. Or there’s one where as Jack is throwing the ball against the Navajo prints, it dissolves into Wendy and Danny leaving the hotel, and she says, “Last one in has to keep America clean, has to keep America beautiful,” which is clearly a joke on the crying Indian PSA from the 70’s which has aged into maybe a campy artifact now. But, back then, it brought every kid to tears and was on the tip of everybody’s tongue. Everybody knew exactly what she was talking about. So here are these two different Native American sequences, and we can see him throwing the ball against the tapestry as we’re hearing them make fun of it at the same time. That was really eerie connecting those dots.