There is a line of dialogue late in Josh and Benny Safdie’s nerve-jangling Good Time that not only neatly sums up but one of the film’s many overriding thematic preoccupations, but addresses the larger motifs of class that have come to define the output of everyone’s new favorite fraternal filmmaking duo. Robert Pattinson’s quick-thinking lowlife protagonist, Connie Nikas, has narrowly avoided capture for the umpteenth time in a single night, having just barely escaped from a run-down amusement park with a motor-mouthed fellow criminal, Ray (Buddy Duress), in tow.

The duo is hiding out in the apartment of a security guard (Barkhad Abdi) they’ve just brutalized. Both men are worn down to the bone by a night of frayed nerves and terrible, life-or-death decisions. Connie, having had enough of Ray’s yammering, snaps at him and essentially tells him he’s a leech. In Connie’s mind, if Ray isn’t “leeching” off government welfare or living behind bars, then he’s useless, a drain on polite society. Ray’s reply, if anything, is the more telling piece of writing on the behalf of the Safdies and their regular co-writer, Ronald Bronstein:

“I probably made more money in the last two years than you did in your whole f*****g life, man. You’ll see, man. A couple years from now? You ever see me drivin’ by in my f*****g Lambo? You’re gonna put your put your f*****g foot so far up your mouth, bro.”

Ray’s flex here involves aspiring to a material want: a luxury car that’s also a status symbol. That Ray’s dream scenario never transpires is almost beside the point. Shortly after this exchange, Connie and Ray are busted by the NYPD for their night of illegal mischief and mayhem, with the former being hauled away in a squad car after the latter decides he’d rather leap from the side of a building than be incarcerated again. This particular exchange ultimately reveals the metric for how the grubby scroungers of the Safdie oeuvre attempt to weigh their own warped version of success.

The characters in the Safdie-verse, no matter what their class station might be, are strivers. They are constantly barreling through life with bare-knuckle abandon, always on the make for the next illicit high or the next major win. For the most part, the restless fringe-dwellers who populate their films exist on the lower end of the socio-economic spectrum, but even when a Safdie character acquires capital (see: 2019’s Uncut Gems), they never stop wanting more. Such is the cruel paradox of capitalism: no matter how much "stuff" we acquire; we may never feel truly fulfilled.

The Safdies grew up in New York City, itself a melting pot of not only assorted classes, but also races, ethnicities, religions, artistic styles, and more. While many films shot in New York capture an overwhelmingly white, moneyed demographic of the city (the films of Woody Allen come to mind), the Safdie’s New York feels more like the real thing: grimy, exalted, diverse, and more than a little dangerous at times. Their characters include wide-eyed urban thrill-seekers, confidence men, heroin addicts who sleep in public parks, basketball phenoms who almost made it, and Adam Sandler as a human trainwreck of a Manhattan diamond dealer. Simply put, the Safdies are interested in the vast spectrum of class and influence that exists in the city they call home. For them to focus on merely one group of said spectrum would feel like a waste of their prodigious gifts.

Heaven Knows What, the Safdies’ shattering junkie romance, feels like the most explicit work that the brothers have ever given us on class. A disorienting immersion into the world of homeless addicts who squat in vacant apartments, beg for change on the street, and spend whatever money they can rustle up on a high that will slowly kill them, the movie is a stark, unsparing, and ultimately quite touching work of American art that will nevertheless register as too painful or disturbing for some viewers.

Those who are repelled by the approach that the Safdies take in Heaven Knows What, however, may want to examine why that is the case. After all, provided they live in a city, these same people probably walk past real-life versions of the characters from Heaven Knows What on a daily basis. It is a film that asks: Why do we ignore the homeless? Why do we refuse to help, or even look these people in the eye when we pass them on the street? The characters of Heaven Knows What have been deemed socially invisible, at least in a class context: All have been punitively forced into a subcategory of individuals whose humanity many of us abjectly refuse to see.

As unrelentingly ugly as it can be at times, Heaven Knows What, like all the Safdies’ work, overflows with the humanity that has been denied to these socially invisible people. To the filmmaker’s credit, they extend said humanity to each non-professional member of the movie’s ensemble. Buddy Duress, in particular, a mesmerizing screen talent and former addict himself, steals many of his scenes in both Heaven Knows What and Good Time, though he is just one example of the Safdies’ tireless insistence on melding the work of Hollywood professionals with first-time performers.

Even before the Safdies broke big, their fixation on class was very much in place. An early short, Acquaintances of a Lonely John, stars Benny as a well-meaning middle-class loner whose repeated attempts at social connection often fail. The only friend the character makes, tellingly, is a dude who punches a clock at a gas station. Two years later, in the disarming John’s Gone, Benny played another, far more alienated weirdo: an apartment-dwelling oddball who sells stuff online and mostly shops/steals from his local dollar store. In the end, John is the victim of a wildly unglamorous robbery executed via box cutter.

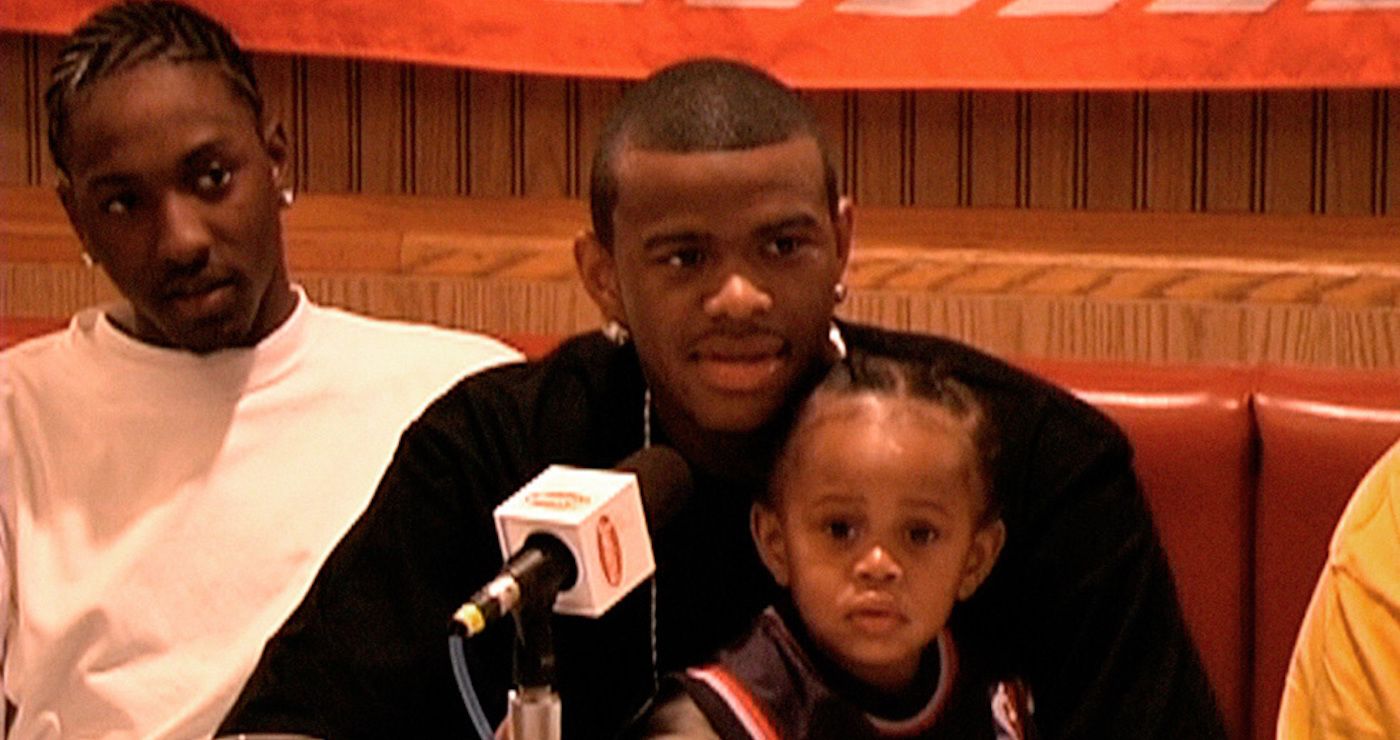

Lenny Cooke, the brothers’ acclaimed documentary about a onetime NBA hopeful from New Jersey, is, among other things, a perceptive and unsentimental look at how a billion-dollar industry preys upon men of color from working-class backgrounds in a manner that’s parasitic at best and actively exploitative at worst. In all of their work, the Safdies seem acutely aware of the class caste that their characters and/or subjects occupy. In fact, in nearly every case, it is an utterly crucial aspect of who they are as individuals.

Take Howard Ratner, the shameless, mile-a-minute gambling addict that Adam Sandler plays in Uncut Gems. More than any other Safdie character, Howard is someone who possesses the comfortable trappings of an upper-middle-class lifestyle. He resides in a swanky if gaudily decorated abode in suburban Long Island. He bets obscenely irresponsible sums of money on basketball games. His wardrobe is an eyesore of garish designer duds. When one of Howard’s employees at KMH, the outlet he owns in N.Y.C.'s Diamond District, comes to him with a slightly out-of-the-ordinary workplace-related issue (he’s just been roughed up by two goons who were sent after his boss to collect a gambling fee), Howard’s solution is to literally throw a Gucci shirt at the guy and pray that his problems will go away.

Like so many mid-level capitalists, Howard’s mistake – or really, one of the many appalling mistakes he makes over the stomach-churning runtime of Uncut Gems – is that he refuses to accept that what he has is enough. There is even a moment, late in the film (those who’ve seen Gems more than once will know the one), where Howard, after enduring setback after setback, finally has the chance to settle his debts and walk away a free man. He can’t. He simply refuses to accept his station in life. In this moment, we see the maniacal, far-off glint in Howard's eyes, even through his rimless Cartier frames. Howard has got his eyes set on a kind of financial and spiritual true north, and he won’t stop scheming or scamming until he’s attained what he believes is rightfully his.

In addition to being brilliant directors, the Safdies are also true students of cinema: the brothers have championed Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves as “the ultimate filmmaking bible,” and also heralded Meantime, Mike Leigh’s masterpiece of Thatcher-era social realism, as a profound influence for them. They seem to understand, on some fundamental level, that themes of class and status have been around for almost as long as movies themselves.

What the Safdies do so brilliantly is sew their probing critique of capitalist desire and entropy into the narrative fabric of the kinds of full-throttle pulp thrillers that regularly put butts in seats. These movies provide excitement first and foremost; it’s only until after the credits have rolled and one has had the chance to sit with the film that the more discomfiting leitmotifs of inequality and injustice begin to sink in, (The horrific, heart-crushing fate of Barkhad Abdi's abused Black security guard in Good Time comes to mind.) The Safdies don’t quite make crime movies as much as they craft sensationally disorienting odysseys that take place within the modern American underworld, or what’s left of it. And yet, even within that vicious cesspool, a dog-eat-dog pecking order persists.

“When you win, that’s all that matters." So goes a quote delivered near the end of Uncut Gems by Kevin Garnett, playing himself. For Howard Ratner, life has been all about winning. Every single second of his measly existence, every benchmark he's ever acquired, is a raised middle finger to his haters, his doubters, and most of all, his creditors. Howard truly believes, in his heart of hearts, that he's a winner.

Except he isn’t. Howard Ratner ends up dead on the floor of his own business, bleeding out as his wife (Idina Menzel), ignorant to her husband’s terrible fate, calls the police after a panicked, frightening phone call. All the while, the lucrative bet Howard has placed on the Boston Celtics finally pays off. The goons who have been chasing our misbegotten hero proceed to rob his store blind, oblivious to the fact that they’re locked inside, and therefore sitting ducks for the cops. Howard is dead, but alas, as the Safdies visualize what many have referred to as a kind of spectacular, psychedelic "journey through the gem” – a narrative bookend, inverted, in this case, so as to mirror the act of Howard’s soul leaving his body – they suggest that there is a kind of reprieve in this tragedy. Finally, Howard Ratner will be free from this cruel world of materialism. Finally, he will know peace.