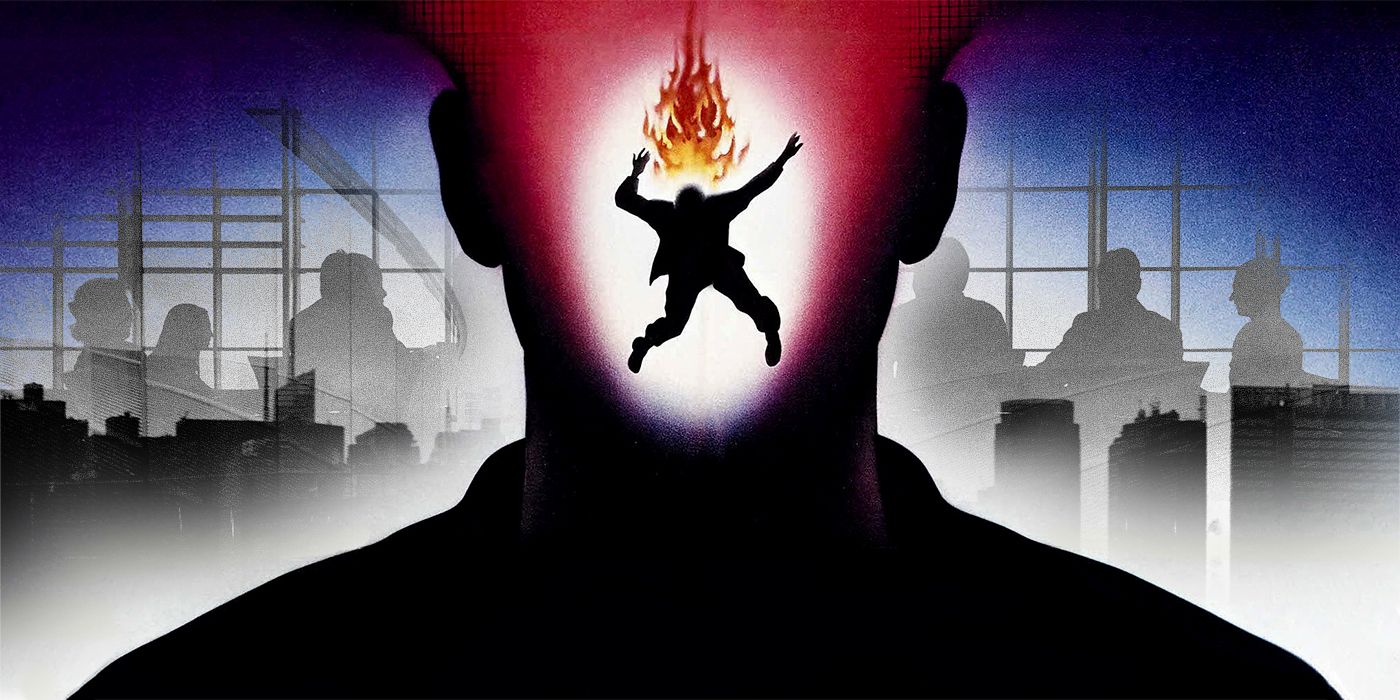

As far as the public is concerned, Scanners might as well be a gif rather than a movie. When David Cronenberg’s eerie sci-fi thriller is brought up at all, it’s because of an infamous scene early in the film, where an evil scanner (basically a person with psychic powers) named Daryl Revok (Michael Ironside) uses his mind to make a scientist’s head graphically, messily explode. It’s an iconic moment that even those who haven’t seen Scanners might recognize, whether from internet memes or from that one episode of The Big Bang Theory where Sheldon and Leonard get into a fight at a symposium. But as impressively gory as that scene is — the special effects required gelatin, leftover burgers, and a shotgun — it could give curious viewers the wrong idea of what Scanners is all about.

The head explosion, as well as Cronenberg’s reputation as a master of body horror, might prime the audience to expect a stomach-churning deluge of blood and guts. But aside from the head explosion and a climax that’s quite literally eye-popping, Scanners is much less visceral than some of Cronenberg’s previous movies, like Rabid or The Brood. For most of its runtime, this sci-fi horror film is heavier on the sci-fi than the horror (albeit the analog, early-'80s kind of sci-fi where they still use tape drives.) Even Revok’s squad of scanner assassins are more likely to use plain old guns instead of grisly psychic powers. But while it may disappoint gore hounds, Scanners is much more than its most famous scene: it’s a taut, eerie take on the political thriller that offers subtle commentary on corporate dominance.

The political thriller, already a prominent genre due to Cold War anxieties, enjoyed a moment in the sun after the Watergate scandal brought trust in the government to an all-time low. Movies like The Conversation, The Parallax View, and Three Days of the Condor might not deal directly with Watergate — in fact, The Conversation doesn’t really engage with the government at all — but they all have a similar atmosphere of clammy, palpitating paranoia. There was a sense, not unlike what many feel in this current moment, that Pandora’s box had opened: paranoia had become sensible, and everyone’s most irrational fears about the government didn’t seem quite so irrational anymore. After all, if the president was willing to order a break-in during an election he was virtually guaranteed to win, what else would he do?

In 1980, Ronald Reagan was elected president with the promise that it was “morning in America,” and a prevailing mood of national optimism meant that the villains in a thriller were more likely to be Soviets than Americans. Reagan’s “government is the problem” approach might have helped soothe some residual Watergate paranoia, even though Reagan’s eventual Iran-Contra scandal would prove to be an even worse example of government malfeasance. (Reagan, unlike Nixon, had a fall guy ready, and got away with selling weapons to America’s enemies scot-free.) Cronenberg, being Canadian, was at least somewhat disconnected from all of this, but Scanners nonetheless seems to comment on this post-Watergate, Reagan era.

Scanners, in essence, is a political thriller without the politics. All the familiar tropes of political thrillers are there, albeit with some sci-fi twists. There are secret conspiracies, regarding both scanners as a whole and Revok’s group of terrorists in particular. Scanners themselves are like an MK ULTRA fever dream, being capable of telepathy and telekinesis. The Men Who Stare At Goats have nothing on them. The mind-reading capabilities of scanners evoke the sort of paranoia that political thrillers use surveillance for. Even the famous exploding-head moment is just a particularly gruesome spin on a classic assassination scene, like the opening of The Parallax View.

The only thing that’s missing is the government. It’s unclear where this story is intended to be set (although it was filmed in Toronto), but governmental forces of any kind, American or Canadian, are conspicuously absent. There are no “men in black” sent to investigate this strange phenomenon, no state department interested in harnessing their power. Even the police barely seem to be present as heads explode in the middle of speeches and meetings are ambushed by shotgun-wielding terrorists. Revok does have a plan to take over the world through an army of scanners, which would imply the existence of governments to take over, but other than that they have zero presence in this film.

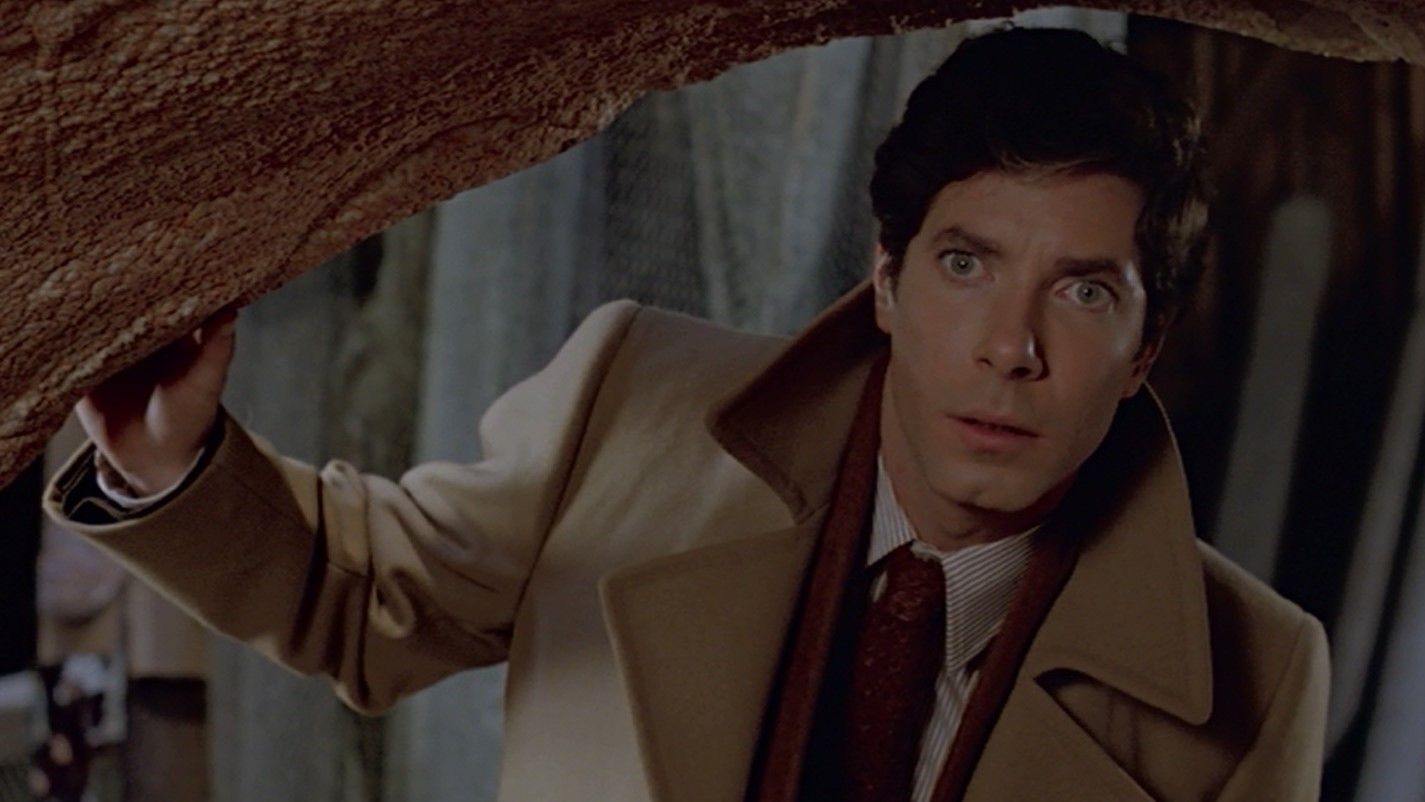

Instead, there are corporations. There’s ConSec, a private military company with suspiciously Nazi-like security guards; they’re attempting to use scanners for their own purposes, and they employ Dr. Paul Ruth (Patrick McGoohan) in order to make that happen. There’s also Biocarbon Amalgamate, a pharmaceutical company being used by Revok in order to distribute ephemerol, the pregnancy sedative that creates scanners. As it turns out, Dr. Ruth was the founder of Biocarbon, and in fact was the creator of ephemerol (and scanners) in the first place. (He’s also the father of both Revok and the story’s hero, Cameron Vale (Stephen Lack), but that’s beside the point for now.) ConSec appears to have limitless resources, and while there isn’t as much focus on Biocarbon it’s apparently powerful enough to kickstart a world domination plot. These companies and the people behind them, are self-interested, all-powerful, and not remotely transparent. In other words, they’re like the bad guys in political thrillers.

Scanners’ view of corporate malfeasance, as well as the science fiction elements, are reminiscent of cyberpunk, but the movie came out a year before Blade Runner defined how that genre looks. Instead of neon lights and holograms, the world of Scanners is firmly in the here and now (or the there and then of 1981); it’s filled with aggressively nondescript office decor and queasy fluorescent lighting. It reinforces the fact that this story about conspiracy and power isn’t set in some far-off science fiction future. It’s contemporary, dealing with paranoia and corporate power, and suggesting that perhaps it’s people, not the government, that are the problem.