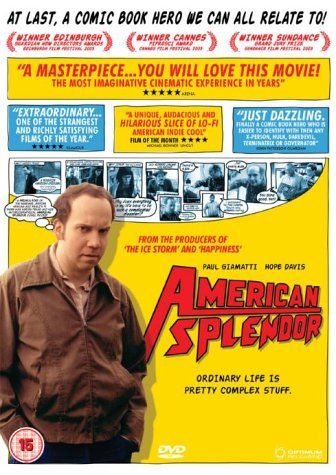

Documentaries have undoubtedly grown closer in style to narrative features over the past 20 years. Similarly, when documentarians Shari Springer Berman and Robert Pulcini moved into the narrative world, they brought their old techniques with them. That first feature, American Splendor, made a big splash, thanks to its fresh and complicated approach that broke standard filmmaking conventions and included material from mediums that varied from comic books and film to television.

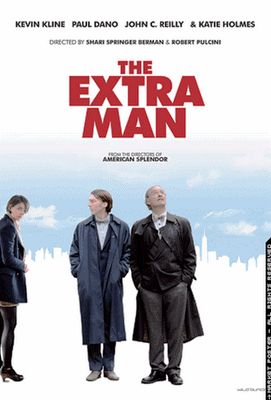

Springer Berman filled us in recently on her latest film, The Extra Man, which continues its gradual, national release today in top 10 markets, with Chicago. Hit the jump for the interview’s audio and transcript, along with info on her new HBO film Cinema Verite featuring Diane Lane, Tim Robbins, Thomas Dekker and James Gandolfini, where she stands on a big divide in the documentary world and a story she’s never told publicly about American Splendor’s late subject, Harvey Pekar.

Springer Berman and Pulcini documented show business before they made films with some of its stars. They directed, in order: a VH1 special on music legend BB King; the award-winning Off The Menu: The Last Days Of Chasen’s which showed the closing of a legendary Hollywood eatery and interviews with some of its famous patrons (Jack Lemmon, Don Rickles, Sharon Stone and more); The Young And The Dead about the renovation of The Hollywood Memorial Park Cemetery and its well-known “residents” and Hello, He Lied & Other Truths From The Hollywood Trenches, an AMC TV documentary based on Hollywood producer Lynda Obst’s 1997 battle scar-filled bestseller about her time in the film industry.

Meanwhile, producer Ted Hope, instrumental in the careers of indie film directors Ang Lee, Nicole Holofcener, Hal Hartley, Edward Burns and many others, was putting together a film adaptation of American Splendor. Harvey Pekar’s comic book series chronicled his life as a file clerk in Cleveland. Several prior attempts died in development, including a film with Oscar-winning director Jonathan Demme, a sitcom with SNL alum Rob Schneider and even overtures from Pekar’s friend, underground comic book distributor George DiCaprio for his son, Leonardo. Hope, who appeared in Hello, He Lied… for Springer Berman and Pulcini, hired them to direct American Splendor. Their re-imagining of Pekar’s work received rave reviews, a spot on a slew of critics’ year-end top 10 lists and an Oscar nomination for Best Adapted Screenplay.

Since then, they’ve flirted with several offers: a biopic of eccentric musician Juan Garcia Esquivel, another on comedian Sam Kinison and a Bride Of Frankenstein remake set in modern-day New York City. Before they returned to narratives, however, the couple made another televised documentary on Hollywood, Wanderlust for the Independent Film Channel. It looked at the impact of road movies on American culture. A big screen adaptation of the bestselling novel The Nanny Diaries, with Scarlett Johansson, followed.

Their latest, The Extra Man, is based on a novel by Jonathan Ames (Bored To Death) and follows the unlikely mentoring relationship of an eccentric, failed playwright (Kevin Kline) and a young man trying to find himself (Paul Dano). It combines various styles and genres of storytelling, as American Splendor did. That creative choice became the starting point for our conversation. The topic quickly shifted to her next HBO film, Cinema Verite, about the 1973 PBS documentary series An American Family that is considered by many to be television’s first reality show. It stars Tim Robbins, Diane Lane and Thomas Dekker as the series’ subjects, the Loud family, with James Gandolfini as the visionary producer Craig Gilbert. Click here for our interview’s audio or simply continue reading for the transcript.

Collider: The mixing of mediums that you use, not only in American Splendor, but also (in The Extra Man) looking back to the techniques that were used in 1920’s films and such. I was wondering what influence that mixing of mediums had, given your background in documentaries where you have so much different source material to use.

Shari Springer Berman: Actually, it has a huge influence on how we make movies, which is funny because I didn’t even realize that people worked differently until I got into the business and be like, “Oh, that’s how you’re doing it.” The thing in documentaries is you tell the story with whatever the hell you can get your hands on. You don’t create everything. I mean, you shoot footage, but then if there’s, like, photographs or archival material or tapes or whatever it is, you just sort of gather everything and then figure out a way to make that work in the editing room to tell a story and we definitely did American Splendor that way. It wasn’t just that we did an interview with Harvey and put that in, but it’s like, we used comics. We used other techniques to tell the story. Every film requires something different that is relevant to the material, but we always come at it that way. It’s like, “OK, well, we’ll write the script and we’ll shoot the stuff, but would it be cool if we brought this in? And right now, we’re doing a film for HBO. We’re actually shooting (Cinema Verite) right now, which is why (her husband and co-director) Bob (Pulcini) is not here, about the making of the PBS landmark documentary An American Family-

Yeah.

Springer Berman: -about the Loud family. And that again is another case where it really requires pulling together all kinds of research and stock footage and different techniques, shooting Super-8, shooting digital, shooting 35 (mm) and just using a lot of different techniques to tell the story.

Just to shift gears to that… Do you think they envisioned television as it is now and especially in the way that it’s infiltrated dramatic television to the point where now, ABC has a show coming on (My Generation) that’s a mock reality show--

Springer Berman: I figured it’d get there eventually.

Yeah, I mean, it’s a take on the Seven Up series [Michael Apted’s documentary series, based on the adage “Give me a child until he is seven and I will give you the man,” started in 1964 with a group of seven-year-olds and has interviewed them every seven years since to see if they reached their goals, where they are in life, etc)

Springer Berman: Seven Up? Ok.

I mean, did you think that they ever thought, you know, 40 years ahead that it would be like this?

Springer Berman: Absolutely not. In fact, the person who produced the show and who was sort of the visionary behind it, this guy Craig Gilbert, got like horribly attacked and the whole family. Like, An American Family did not get well reviewed. People thought it was immoral. Like, “What kind of family would subject their family to this?” And they thought they were very callous and bourgeois and trying to show off their money and then judged Pat Loud, the mother, because (her son) Lance was openly gay. He was the first openly gay character on television, or person. And they judged her for accepting him. And, like, “What kind of mother would accept a son like that?” I mean, they did not get celebrated. They got attacked. They were just far too ahead of their time. And (noted anthropologist) Margaret Mead - Craig Gilbert did a documentary about Margaret Mead (Margaret Mead’s New Guinea Journal) before he did American Family - actually came forward and said that she thinks that this is one of the most important things to happen to our culture since, like, the invention of the novel and that soon, cameras will be, like, the next stage of anthropology. Like, studying people and culture. Margaret got it. Like in 1973. She was the one who saw the future and realized that, we were gonna get there. It just took a really long time.

But is it almost the Jurassic Park thing where just because you can do it, means you should?

Springer Berman: I think there’s a huge difference between what was going on in those days. You know, American Family and even with all the cinema verite movies like the Maysles (Albert and David made the groundbreaking Rolling Stones documentary Gimme Shelter before An American Family and debuted Grey Gardens two years after it) and the Pennebakers (D.A. Pennebaker directed the Bob Dylan documentary Dont Look Back a few years prior to An American Family) and there was a naïveté amongst people being filmed. I mean, people live on video right now from the time they’re born. I’ve been to parties where people are videotaping the party and then watching it while the party’s still going on. You don’t experience anything unless you’re watching it, you know? And I think in those days, people weren’t aware of it, so I actually think you could get some element of truth. Any time you choose a frame, you’re being subjective, but I think there was an element of truth in that people really weren’t that aware of the camera, weren’t always playing to the camera. I mean, I think at first people were stilted, but then, the more the cameras were around, the more they got comfortable. I think now people are raised with cameras. There were these documentary ethics that existed in those early days. You couldn’t really tell people what to do. You couldn’t really direct people. I mean, I’m sure people broke it, but you were really supposed to be a fly on the wall and let things happen. Nowadays, the producers tell everybody what to do. It’s practically scripted. So, I don’t know if there’s that much in common anymore. I mean, it’s the same format, but I don’t think it is reality, anymore.

Albert Maysles was on a panel that (President of HBO Documentary Films) Sheila Nevins was moderating with D.A. Pennebaker --

Springer Berman: Wow, that sounds great

It was really interesting because Maysles is so opposite the Michael Moore school of documentary and was very against it—

And D.A. Pennebaker was in favorite of it and Maysles was saying (Moore) treats people poorly and Pennebaker was looking bigger picture at (Moore’s) message and, in looking at your style of documentary and your take on documentaries and now that you’re doing (Cinema Verite), where do you fall between Maysles and Pennebaker and Michael Moore?

Springer Berman: I just think they’re different. Like, I don’t think one is right and one is wrong. I’m actually a big Michael Moore fan. I actually saw Roger & Me before anyone had heard of Michael Moore at the first screening at the New York Film Festival. I, like, bought a ticket cause it looked interesting. I didn’t know what to expect. And from the minute it starts, it’s his perspective. He has a voiceover. It’s a first-person voice-over. It’s like, “Here I am. I’m, was born in Flint, Michigan. This is my life story, this is my perspective.” So, he’s telling you who he is and who his perspective is and he doesn’t pretend like he’s making an objective documentary. The Maysles come out of a very different school and they were trying to create a fly-on-the-wall (aesthetic). Have the filmmakers disappear as much as possible. I like both. I can’t make a Michael Moore-style movie because I don’t have Michael Moore’s personality and I don’t have his wit. Like, I would never put myself in the center of a movie, but it doesn’t mean I don’t respect it and think it’s fabulous. It’s just different.

There’s a certain transcendence through banality in American Splendor with the little things and (similarly, commonplace events) in The Extra Man become adventures. Is this medium that for you, as well, where given the size and the scope and the space of the screen that it blows things up that THAT’S an interest of yours? It may seem small just in regular daily life, but all of a sudden, it becomes something so much more when you put it onscreen.

Springer Berman: Yeah, I think I am very interested in the quotidian things in life and I like seeing like, an action movie or a movie like Inception. I’m fascinated with that kind of filmmaking, but it’s not what I do. I kind of think that the little things and little moments and little interactions can say a lot and can be just as fascinating or just as interesting as a chase sequence. If it’s specific enough and unique enough. And I guess again, it comes from coming from documentary filmmaking where I really love real things and real people and real moments and, you know, I kind of look for that in material. The Extra Man reminded me of American Splendor in that way and the characters were extreme and kind of interesting a**holes. Like, you know, Henry’s kind of like, a lovable jerk, which Harvey (Pekar) was a little bit, too and I like that specificity. I like those layers. You know, and I like things about people who are flawed.

When you had Kevin (Kline) onset, how much of it was scripted? How much of it was improvised? ‘Cause there’s an awful lot that seems so in the moment. It feels like little parts are, are improvised.

Springer Berman: Well, Kevin is a fantastic actor, so things that might feel improvised might not be. But that being said, he definitely, there were certain things that came from Kevin. Henry Harrison is such a beautifully written character. Jonathan (Ames) created him based on someone he knew in real life and the character in the book is incredible and I think Kevin really connected with him very deeply and had some similarities with him and so I think he knew what Henry would do at any moment and would sometimes improvise things that were just perfect and brilliant. But I’m curious, what, is there one thing off the top of your head? I’ll tell you if it was improvised.

There’s the point (after Dano and Kline fib their way past an usher to sneak into the opera) where (Kline) says: [“You could land yourself a walk-on part somewhere. Perhaps off-broadway.”]

Springer Berman: Yeah. That’s improvised. I mean, it was really funny because I saw Kevin like a few months after we shot. We, he came into do some ADR (vocal dubbing sessions) and he was so different and I suddenly remembered, like, “Oh my God, he’s not Henry Harrison, he’s Kevin Kline.” Although they do have a lot in common. They’re men of the theater, very erudite, and sometimes disapproving in this, kind of fatherly, lovable way. Like, they have similarities but yet, they’re different people and it took me a few months of not seeing Kevin to remember that “Oh, he’s not Henry Harrison.” He’s just that good in, in character so much when we were making the film. All the time in character.

We don’t have that much time left, but I’d be remiss not to ask you about Harvey Pekar (who died last month at age 70). And I was listening back to some old interviews that he did and one (that aired August 13, 2003) with Elvis Mitchell on The Treatment. He called you “the perfect directors” for American Splendor.

Springer Berman: (Visibly moved) Mmmm, that’s so sweet.

And he said, (paraphrasing) “I didn’t want to interfere at all except I just wanted (legendary jazz musician & composer) Joe Maneri and (the Marvin Gaye song) “Ain’t That Peculiar” on the soundtrack and that was it and, you know, let them do it because they were so in tune with it. “ And I wonder, seven years after (American Splendor), how you look at things differently after having that experience.

Springer Berman: Oh my God. My whole life changed because of that. I mean, first of all, Harvey was honestly one of the greatest people I’ve ever met in my entire life. Such an original. Such a brilliant man. I mean, they should put his picture in the dictionary for “working class intellectual.” And also like, a lovable, kindly a**hole. Like sometimes he would be difficult, but you never didn’t love him. He was a kvetch. (Laughs) He would complain, but he was the greatest. It was weird. It was such a long experience ‘cause we started shooting right after 9/11. I mean, we were in pre-production. Our first day of casting was on 9/10/2001. Downtown. Like right near the World Trade Center. So, we went through all of that. We then made the movie.

What was that day (9/11/01) like? The second day of pre-production. How close were you?

Springer Berman: Well, the only reason why we weren’t downtown is ‘cause nobody in the film business starts work at 9:00 in New York.

Yeah, of course.

Springer Berman: So, we were, we were up on the Upper West Side where I live, but my production office was on Canal and Varick with this beautiful view of the World Trade Center. And all the people had to be evacuated, you know, watched the buildings come down. My casting director, Ann Goulder, called me crying. I mean, it was insane. Ted Hope, who was the producer, I remember I said, “Do you think we should try to get office space in midtown?” Cause it was, air was hard to breathe and-

Right.

Springer Berman: It was like a Godzilla movie down there. It was like emergency vehicles.

Yeah, I remember that.

Springer Berman: It was crazy. We stopped working for like, a few days and then went back to work and he was like, “No. Downtown has to come back.” I don’t know if he was just being cheap or (laughter) being patriotic, but whatever it was. So, every actor that came in to audition would cry. I mean, it was just emotionally raw and crazy. And I’m a New Yorker. I grew up in New York and we had to leave and go to Cleveland. We drove because at that point, they weren’t even like, flying that much. It was just the craziest time.

Yeah.

Springer Berman: I mean, I remember sitting down with Ted and saying, should we do this?” Ted was like, “Do we even want to make movies, anymore?”

Yeah.

Springer Berman: I mean it was that, like, soul searching. Then we went to Cleveland and had that intense experience and like, Paul Giamatti (who played Pekar in the film) and Harvey like completely bonded and Harvey would come to set every day and eat the free lunch and then take a nap. (Laughs)

In a trailer?

Springer Berman: No! Like right on the set! Especially cause it; it looked like his apartment so he’d just lie down. He was comfortable. (Laughter) And like (Pekar’s wife) Joyce would take food home and (his daughter) Danielle would come in. It was just magical. It was like an incredible- I know this sounds crazy. I haven’t told this to anybody, so I’m, this is gonna be the first thing, but the first day we started, our call time was like at 5am and it was my first feature film and it was still night and there was the craziest meteor shower like I’ve never seen in my life. Like the whole sky was ablaze, ask anyone who was on the movie. It was like, surreal. And I was like, “This is weird. This is gonna be the beginning of something very, very, very strange.” And then, shortly after we finished the movie, Harvey got diagnosed with cancer again and got really, really sick and really depressed and went through a really tough time. And I didn’t think he would be well enough to go to Sundance. And then Joyce got him up and got him well and then he came to Sundance and he was, like, amazing. He got up and he just entertained everybody and then, it was like the craziest thing.

We went to (film festivals together in) Cannes (and) Deauville and we, we traveled to all these places and all these festivals. Went to the Academy Awards with Harvey Pekar in, like, a cheap suit that he got in Cleveland, walking down the red carpet and I remember sitting in the Oscars, like turning around and seeing him, his head buried in his hands like, miserable, like, “This is so long man, I hate it!” You know, we went through all these crazy things together. It changed my life. It was just the most amazing experience and, what was most moving to me was when we found out about Harvey passing, I was shooting, but when I came home, I like, first of all, I got more e-mails than I’ve ever gotten in my life. Like 150 e-mails, from anyone I’ve ever met and everyone who worked on the movie. It touched them all that much. But then I Googled and it was like a massive outpouring, all over the press. Like Twitter and, this and that, I was like, how did Harvey touch so many people? I was like, “I didn’t realize he was that famous.” And I knew that would’ve been so important to him. He really wanted recognition. He really wanted his material to be seen, his books and his comics to be seen by a bigger audience. It made me smile. Like, even though I was sad, very sad, he was only 70, to have lost him, and he was really doing well, it was knowing that (smiling) he was famous. He was, like, a big deal. I’m like, this is amazing coverage. I knew that Harvey would be so happy at this. So, that really moved me.