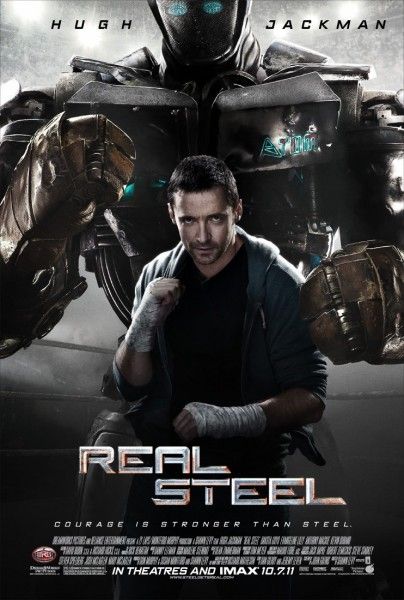

Real Steel is a true underdog tale that combines the grand spectacle of robot boxing with the grounded story of three abandoned beings – a father, a son, and a discarded robot – who, together, have the chance to become real heroes. In 2020, boxing fans have become bored with watching human beings fight each other, so the sport has evolved to the point where robots pummel each other to the death. Washed up, former heavyweight Charlie Kenton (Hugh Jackman) begrudgingly teams up with his long-abandoned son (Dakota Goyo) to turn a junkyard robot into the champ they believe he can be.

At the film’s press day, director Shawn Levy talked about the challenge of getting the robots to work, the decision behind not giving his star robot Atom a face, why he feels he is able to direct kids so easily, creating his own version of the year 2020, the Simul-Cam B technology used to shoot the film, and his personal philosophy for directing. Check out what he had to say after the jump.

Click here to listen to the audio of this interview

What was the biggest challenge, as far as getting the robots to work in the film?

SHAWN LEVY: Honestly, it was pretty smooth. Obviously, the decision to build real robots was a bit unusual because, in 2011, when everything can be done digitally, on most movies we see, everything is done digitally. It was this throwback notion to build real remote controlled robots, but we just felt it would give the movie the look, the feel, the performances and the reality that was key. I’m super-happy we did.

It all went pretty smoothly. We had amazing remote-control puppeteers. Only one time, Ambush was in the middle of a take, and he was standing on that lift gate with Hugh [Jackman], at the County Fair, and his chin started going down. I guess his hydraulics had gone haywire and his chin went down, crushed into his collarbone and his whole bottom half of his face got stuck in his chest plate. That was very scary. That was 25 minutes of standing around and waiting to see if Ambush could be saved. Fortunately, the folks at Legacy were able to save him and we carried on.

I also have to say that we made what felt like a scary choice, at the time, to make our hero robot be the only one without a face. Atom is not just our hero robot, but our most human robot, and he has no face. I was amazed at how the puppeteers, in the way they moved Atom, were able to humanize him. Just based on the reaction we get from audiences, people love Atom like they love Hugh or Dakota [Goyo], and that’s a big testament to the puppeteering of the remote control.

Why did you decide on no face for Atom?

LEVY: Because I knew that what mattered more than Atom’s personality is Atom’s magic, and sometimes magic is created by ambiguity. The ambiguity and the uncertainty gives Atom his soulful quality. When I was reviewing the robot designs with Bob Zemeckis, he said that that mesh would become the screen that people project their feelings onto, and that the absence of features on Atom is going to make that screen what people project their opinions and feelings onto. Sometimes Atom looks like he’s smiling. Sometimes Atom looks like he’s proud he just went the distance. Sometimes Atom looks sad and lonely. I found it really interesting to test people’s reaction to that robot and see the range of things that people read into titanium mesh.

What was it like to have your kids in the movie?

LEVY: The truth is that my girls listen really well. It’s hard to find kids who can just be natural on screen. My two elder ones had been in A Night at the Museum 2, and I put three of them in this. I now have four. They’re pretty good. At one point, Hugh started improvising and my little one, who is three, turned to me and said, “Daddy, what are these words? Why is he saying these words? Those aren’t his words! Those aren’t your words!” And, Hugh was like, “Oh no, mate, I’m improvising. This is what we do.” I had to explain what ad-libbing was, and then she rolled with some improv.

Why do you think you’re able to direct kids so easily?

LEVY: It’s really interesting because I sure do keep going back to it. Even when I was a kid, I had a good thing with kids. To this day, if I go to a birthday party with one of my kids, I swear to you, I am so much happier hanging out with my kids and their friends than talking to the grown-ups. I don’t know if it’s that my own childhood felt brief, or I grew up too fast, or I was pushing myself too much at a young age, but I do feel like I am clinging to a certain childlike quality in myself, as a result of a childhood that was sometimes complicated. I was grown up fast, by virtue of certain circumstances, so I think that’s a bit part of it.

With kids, you have to change your modality, day to day. There were some days, with Dakota, where I just stayed out of the way and he was awesome. There were other days where we had to do 10 takes until I got something usable. There were other days where I could tell he had said the lines too many times, so I would throw improv at him, just to make him say new words. Kids eventually don’t hear the words anymore. Some of the lines in the movie were the result of that improv.

Ultimately, the craziest technique I used, that bore the most fruit, was for the climactic scene of the movie where he and Evangeline [Lilly] are watching Hugh’s redemption moment. I didn’t let anyone talk to Dakota. I did not talk to Dakota. I did not tell him what to do. I said, “I’m going to play some music. Just go with the music. Whatever you feel, that’s fine.” The last thing you want to say is, “Cry.” If you tell an actor to cry, you’re dead, especially a kid. It’s too much. They tighten up. So, I played a piece of music and he went with it, and he brought that performance that is so beautiful.

What were you looking for, when you were casting the role of Max?

LEVY: I was looking for something other than acting talent. I needed the acting talent, but I needed a kid who could also be interesting to watch when he was not acting. With Dakota, it was less about how he said the lines and more about what he exuded between the lines. With a movie like this, I needed what Steven [Spielberg] calls an authenticity. It’s something that makes you feel that you’re watching a real human being, who’s a real kid, in such a way that you root for that kid. If you feel that you’re watching a kid act, not only ain’t you rooting for him, you don’t even like him. He’s annoying. We’ve seen those performances. This kid is exposed. He’s in every frame of the movie. So, there was a moment, after about six weeks of looking all over the world and not being able to find him, where I was like, “Maybe I shouldn’t make the movie. Even if we do everything right, if the kid isn’t one-in-a-million excellent, the movie can’t be excellent.” And then, we found Dakota.

What was it about Evangeline Lilly that you felt elevated that role?

LEVY: I auditioned a lot of women, and everyone told me, “Just forget Evangeline.” I was really hung up on Evangeline because certainly it would be nice if she was pretty, but I needed someone who you believed had grown up in a man’s world, and who had a strength and a toughness that was not at the expense of her being womanly. I wanted this Charlie-Bailey relationship to have a lot of subtext. We don’t say very much about what went on between them. The studio was like, “Don’t you want to actually say what they are?,” and I was like, “No, I really feel like the elegance is in not quite pinning it down.” Everyone said, “Evangeline quit acting when she finished Lost.” I was a big fan of Lost. I have friends who offered her big roles in big movies, that are big titles coming out in the next four months, and she turned it all down. She just wanted to live in Hawaii and quit acting. Everyone said, “Don’t bother,” but I sent her the script.

She showed up in L.A. a few days later, and I said, “Everyone said you’re out of the business.” She said, “This thing made me cry. I want to put stuff like this in the world. This movie is going to make people cry. I want to be a part of it.” That’s what it was. And, indeed, she brought everything I hoped she would. She’s magnificent to look at, she’s soulful, she plays all the subtext, she’s sexy with Hugh, and that kiss on the roof is great. Someone said, “Did you consider actually having them go at it?” I was like, “No! First of all, that’s a stupid question. Second of all, I’ve really never seen a sex scene that I actually found sexy.” I wanted romance, not sex, and she brought all of that. And, I believed that she was a woman who had grown up and been shaped in a man’s world.

How did you go about creating the world of 2020?

LEVY: The key was to not do the same futurism we’ve seen in movies. I wanted a future that felt within relatable radius. I love a Blade Runner or a Minority Report, as much as the next guy, but Real Steel was always going to live or die on audiences connecting with the characters. To connect with the characters, you need to connect with the world. If the world feels vaguely familiar, I believe the characters will feel relatable. So, that was everything. If I just wanted to make a robot boxing spectacle, I would have gone deeper in the distance. But, I wanted to keep it a little closer to home, so that we had a chance of keying into the world and the characters.

The catch phrase was retro-forward. Contrary to how many movies do it, your cell phone looks different than it did five years ago and my laptop does, but a diner is still a fucking diner, and a landscape is still a landscape. The world isn’t actually changing in its core visuals, to the extent that movies often embrace the conceit that it is. It’s changing in the technology, way faster than in the landscape, so that’s what I went with. The result I wanted was almost a timeless, iconic America, rather than a temporally specific America, just because I felt like I hadn’t seen that before.

Can you talk about the Simul-Cam B process and what that gave you, as a director?

LEVY: Motion capture is when you have an actor do something physical, in a data sensing jumpsuit, and the computer stores that movement and converts it into their fictional character. In Avatar, Sam Worthington became Jake Sully, the Na’vi. In our movie, every robot was a boxer or an MMA fighter, and we converted them instantly into their robot selves. Where it gets tricky, and where we did stuff that Avatar didn’t have the need for, but laid the groundwork for, is that Avatar took those captured performances and put them on Pandora, which was a created, digital universe. We went to Detroit and we did shots of real fight venues. Hugh was in an empty ring, but when I was looking through my camera, I could already see the robots fighting. If I decided I didn’t like the shot, the Simul-Cam B re-calibrates the perspective from which I’m seeing the robots, so that it matches the change. It’s crazy! The reason that these fights feel so visceral is that you’re not operating the camera by guessing or assuming that some animator that you will never meet will draw it in. You’re operating to the fight, from an infinite number of angles. That’s mo-cap with Simul-Cam B.

Does that mean the next movie you do can’t live up to this?

LEVY: Who knows. Clearly, I’m in a moment, or a stage of my career, where I am really enjoying these broadened opportunities. I have no need to keep doing more complex movies. I do have an appetite for these big canvas paintings, so to speak, and one does tend to have to use technology for that. But no, I’m not going to try to top myself, as far as complexity ‘cause this one was a crash course. I would sit in the early meetings on Real Steel, and it was like that feeling in high school when you were in a class where you were so fucking lost that you would giggle. I would be in chemistry or physics and just be like, “I actually don’t even understand the words.” We’ve all had that feeling. That’s what it was like, for the first few weeks on Real Steel. I would sit in these mo-cap, Simul-Cam meetings, at the head of the table, and fake it.

Eventually, after a couple of weeks of being completely lost, I went to my team, which thank god, is the same group of people that work with Jim Cameron, and I said to my executive producer and A.D., “I need a crash course, right now. I’m going to open my mind and we’re not giving up until I understand it.” And, he taught me every day, just him and me, and I had no shame about saying, “No, go back. What is that word you just used? I don’t even know what that word means.” Once you’re over 25, how many of us learn something brand new? It doesn’t often happen. It’s no fun, at first, because you feel like a dummy, and we all build lives so that we feel pretty good about ourselves. So, to put myself in a position where I felt that lost, but then felt the mastery once I got it, was fun. It went from being no fun to very fun.

What is your philosophy for directing?

LEVY: The first thing that comes to my mind is by any means necessary. The job is to get your actors to where they need to go, and figure out a way. You may get to use one of the techniques you’ve used on other movies, or you have to maybe come up with something on the fly. Whatever it takes, the job of the director is to be the leader and to get your actors where they need to go. That’s a philosophy that I have. I try to make a partnership with the actors. The more I become bonded with them, the more I know them and the more I know what modalities are going to work. On a really intellectual actor, I use music a lot because it short-circuits the intellect and bypasses rational dissection. Other actors want to talk it into the ground, and sometimes you have to literally pretend it’s interesting to you. That’s the job.

The other thing is that I’m trying to put stuff out there that has the feeling that I would want in movies. Though I want to keep broadening, it’s never going to be nihilistic, it’s never going to be gratuitous, it’s never going to be cynical, and it’s never going to be undermined by its own ironic cleverness. That’s just not how I live my life, it’s not how I want to do my work, and it’s not what I want in my work. Nobody wants to go to work and be miserable. I don’t, and I don’t want that for the people who are working for me. When you’re directing, you’ve got 120 people giving their talents to you, knowing that there’s only one person who’s going to get all that glory. Two, if you could the movie star. I have craftsmen and artists giving their art and talents in the service of my story and my vision, so they deserve to be treated really respectfully. I believe in that.