The animated film has come a long way since 1937, which saw the release of the first feature-length animated movie, Disney's Snow White and the Seven Dwarves. From experimental and short films to series for children and adults, animation has continuously evolved over the decades to become one of the most dominant mediums across the entertainment spectrum. The biggest shift occurred in the last 30 years, when computer-generated, 3D animation overtook traditional, hand-drawn, 2D animation as the most successful format. The early years of this shift revolved around several creative and business figures, including one Jeffrey Katzenberg. His reluctant embrace of the medium — in the form of 2001's perennial classic Shrek — helped position DreamWorks as Pixar's only early rival, and cleared the way for 3D to dominate the marketplace to this day.

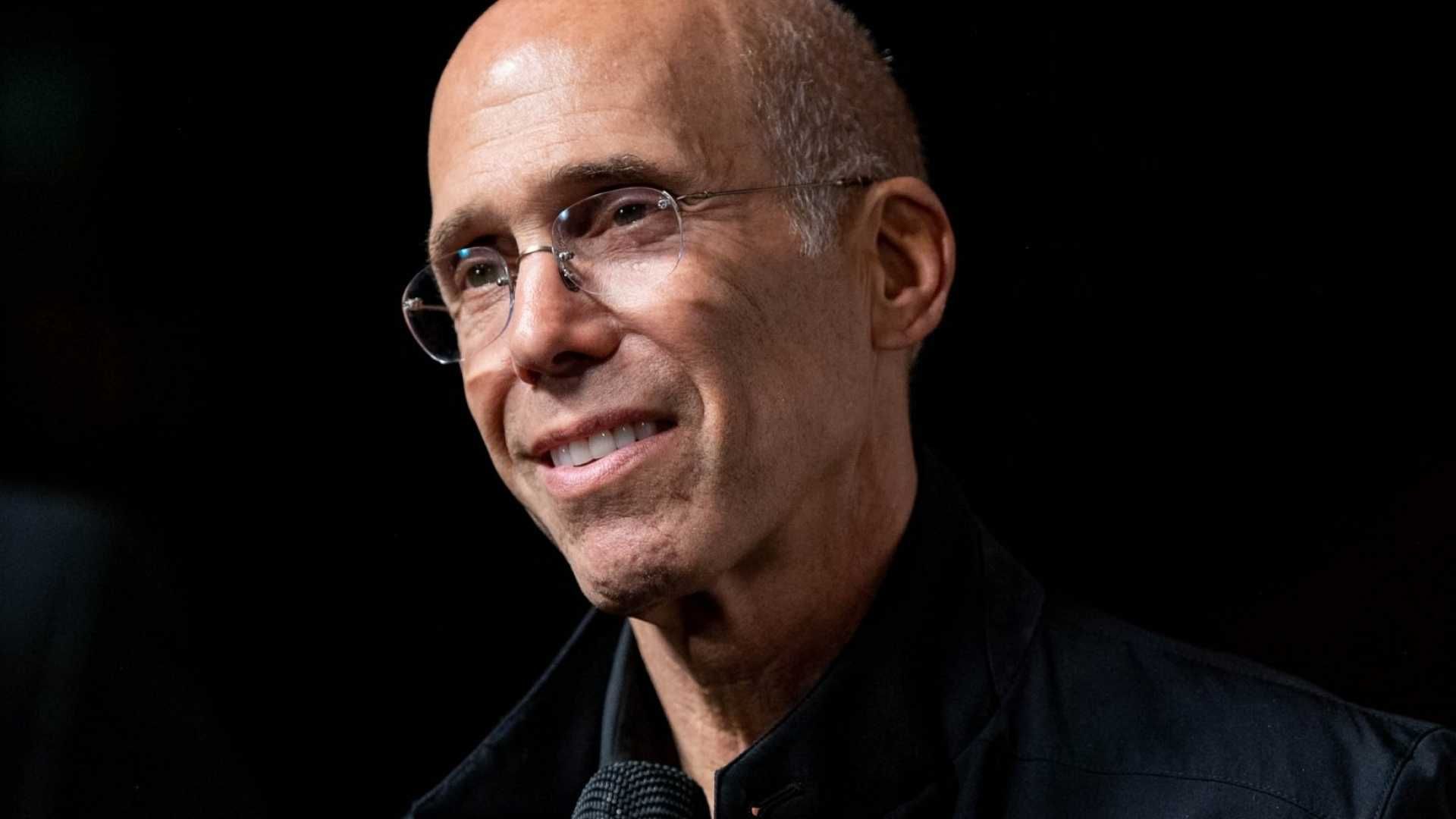

Katzenberg was a co-founder of what was originally called DreamWorks SKG, before becoming CEO of DreamWorks Animation LLC, the spin-off company formed in 2004. His legacy as one of the few moguls with ties to Hollywood’s 1970s Golden Age has been somewhat tarnished by the high-profile failure of short-form content platform Quibi, which Katzenberg launched in 2018 alongside former eBay CEO (and failed California gubernatorial candidate) Meg Whitman.

Katzenberg was a hard-charging movie executive who swept through Disney in the 1980s and upended, streamlined, and renewed both their live-action Touchstone wing and their once-dominant animation department. As recounted in Nicole LaPorte’s The Men Who Would Be King: An Almost Epic Tale of Moguls, Movies, and a Company Called DreamWorks, under Katzenberg’s tyrannical direction, a staid, lax generation of animators were shown the door. He brought in live-action screenwriters (like Ted Elliot & Terry Rossio) to script animated features, foresaw the rise of animated musicals, and effectively began the trend of hiring major stars to voice characters like the genie in Aladdin (Robin Williams). Katzenberg oversaw the Disney Renaissance: The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, and mega-hit The Lion King all originated under his watch.

Once Katzenberg jumped ship to join Steven Spielberg and David Geffen in creating DreamWorks, he predicted (presumptuously) that their 2D animated films would rival Disney. Ironically, his devotion to the fading traditionally-animated feature film would lead to his embrace of 3D animation, and help reshape the medium.

Pixar & 'The Prince of Egypt'

As Disney reached the zenith of its commercial and artistic animated accomplishments with the 1994 release of The Lion King, Pixar had yet to release a long-promised feature film composed solely of computer-generated animation. Having been bought from original owner Lucasfilm by Steve Jobs, Pixar had reduced its staff and was on the brink of another sale before the groundbreaking Toy Story debuted in 1995.

Katzenberg and Pixar co-founder John Lasseter were on friendly terms early on during the DreamWorks years, but this relationship would eventually sour. While Pixar spent the middle chunk of the decade consistently advancing the art of 3D animation, Katzenberg’s bitter, acrimonious split from Disney fueled his ambition to not just match his achievements at the Mouse House, but surpass it. His intended instrument for this dubious goal? An animated biblical epic, The Prince of Egypt.

The studio’s first animated feature originated from the same place as many other questionable ideas DreamWorks would attempt: one of Steven Spielberg’s whims. Envisioned as a “serious” retelling of the story of Moses and the Ten Commandments, the project became something of an obsession for Katzenberg. The story of how Moses led his people out of Egypt and into the promised land paralleled neatly with Katzenberg's exodus from Disney following an epic falling out with Michael Eisner after the death of Disney president Frank Wells.

Wells was the No. 2 man at Disney, a calming influence on both Eisner and Katzenberg, two men whose fiery ambitions often resulted in a clash of personalities. Katzenberg — who counted David Geffen as a friend and mentor long before the creation of DreamWorks — had been pushing for a promotion. He saw himself as the logical choice to fill Wells' position, and felt betrayed when Eisner announced he'd be taking on those duties himself. Their relationship deteriorated quickly after that, until finally Katzenberg left. (Read the entire fascinating saga in this detailed piece from 2014 by Kim Masters.) The Prince of Egypt would be Katzenberg's first big assault on the studio that had been his home and made his career.

Bugs & Antz

The post-Katzenberg Disney animated releases certainly lacked the kind of luster of The Lion King's $1.06 billion worldwide box office haul (not to mention merchandising, direct-to-video sequels, and the Broadway stage show, which would go on to make the studio another billion dollars). Releases like Pocahontas, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Hercules, and Mulan may have their devoted fans and certainly made money, but none could match The Lion King's once-in-a-lifetime cultural impact. Unfortunately for Katzenberg, neither could the traditionally-animated features from DreamWorks.

Katzenberg threw himself into the development and production of The Prince of Egypt, but for all the technical prowess of the creative team (featuring many artists and animators lured away from Disney), the film opened to a lackluster $14 million, topping out at $101 million domestically. This was hardly the earth-shaking animated debut Katzenberg had promised.

While Katzenberg remained stubbornly devoted to the medium that had made him, he had also partnered with the Redwood City, California company Pacific Data Images. PDI had contributed to the visual effects of high-profile blockbusters like Terminator 2 and Batman Forever, and essentially became the computer animation wing of DreamWorks before merging with the studio altogether.

DreamWorks' first 3D animated feature, Antz, was released a few months before Pixar's A Bug's Life, and the dueling insect premises became a source of controversy. ("Jeffrey stole my idea," Steve Jobs, who owned Pixar at the time, would say in interviews.) Antz was fairly well-received at the time, but its $81 million domestic box office take (on a $90 million budget) was blown away by the $363 million worldwide haul of A Bug's Life.

Meanwhile, a project Katzenberg considered to be a low-level near-experiment would eventually emerge as DreamWorks Animation's first major franchise.

'Shreked'

William Steig's 1990 children's book is very different from the Shrek movie we know and love. The 30-page book depicts an ugly creature who spits fire and terrifies the countryside. The plot roughly resembles the movie's, as Shrek uses his flame breath to rescue a princess, who turns out to be as ugly as him. The two get married, living "horribly ever after, scaring the socks off all who fell afoul of them."

Shrek started as a small side project after Katzenberg agreed to acquire the rights to the book. For years, a revolving door of writers — such as Ted Elliot & Terry Rossio (Pirates of the Caribbean) and Joe Stillman (Beavis & Butthead Do America) — and directors like Henry Selick (The Nightmare Before Christmas) would come and go, with none of them able to crack Katzenberg's desired tone of "irreverent." Shrek became known as "the Gulag," a place they sent you when you were perceived as unable to hack it on The Prince of Egypt. Enter Andrew Adamson, a special-effects director at PDI, and storyboard artist Vicky Jensen.

Adamson proved capable of pushing back against Katzenberg's intense, sometimes overbearing scrutiny. Veterans of the project credit Adamson with trusting the creative ingenuity of his storyboard artists and animators. Following the tragic death of Shrek's original voice actor Chris Farley, fellow Saturday Night Live alum Mike Myers stepped into the role. Over time, the big green ogre lost the misshapen look and mean-spirited energy of earlier whacks at the material. Eddie Murphy was brought on board to play Shrek's sidekick Donkey, and his brilliant comic instincts shaped the film even further, with the animators constructing scenes around Murphy's improvisations. Donkey became a scene-stealer, capturing that "irreverence" Katzenberg had wanted.

Shrek premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 2001, in competition for the prestigious fest's highest honor, the Palm d'Or. Shrek won over the stuffy crowd, and went on to make over $484 million at the worldwide box office, not to mention winning the first Best Animated Feature Academy Award. (There were significant internal disagreements over who should accept it before Katzenberg reluctantly agreed to have Adamson step up.) Shrek's enduring popularity is undeniable, and its influence on the two decades of computer-generated animated films since has manifested in a broad tonal approach that can be felt in everything from the Ice Age series to the Despicable Me/Minions franchise.

The Real Road to El Dorado

Despite Shrek's success — which in retrospect resembles the impact of Disney Renaissance classics like The Lion King and Aladdin — Katzenberg remained stubbornly devoted to traditional, 2D animation. The Road to El Dorado, released the year before Shrek, was envisioned as a light-hearted romp in the tradition of a Bob Hope/Bing Crosby buddy road movie. After years of meticulous, hands-on development by Katzenberg seemed to result in a confused mish-mash of styles and tones. That film topped out at $76 million worldwide, far less than its estimated $95 million budget. 2002's Spirit: Stallion of the Cimmaron fared a bit better, but its anemic reception by critics — mirrored by that of 2003's Sinbad: Legend of the Seven Seas — signaled a change in the market for animated films.

After Sinbad, Katzenberg turned his back on the medium that launched him to a new level of power and influence. Just as Shrek's reference-happy attitude spawned inferior "fractured fairy tale" ripoffs like Hoodwinked! and Happily N'Ever After, it also created a path and template for Pixar's competitors. Few would argue that a kiddie-crowd-pleaser like Boss Baby is on the same level as Soul or Inside Out, but DreamWorks' best animated releases — How to Train Your Dragon, Madagascar, the first two Shrek movies — sought a respectable approach to artistry and audience appeal. This approach is reflected in some of the best non-Pixar animated films in recent years: Encanto, the Sing movies, this year's The Mitchells vs. the Machines.

It was a long and bumpy road for Katzenberg: from Disney to DreamWorks (his fallout with Eisner over an unpaid bonus yielded a nasty public court battle), from The Prince of Egypt to Shrek and beyond. The quality of DreamWorks' animated sequels may inevitably dip over the years (Shrek the Third, anyone?), but the state of modern 3D, CGI animation would not be the same without his devotion to and nostalgia for the traditional animated form.