[NOTE: This is a re-post of our Silence review from December, it is currently playing in select cities and expands to a national release, Friday January 13]

In 1988, Martin Scorsese was given a gift of Shūsaku Endō’s 1966 award-winning novel Silence. The offering came after the Vatican had declared Scorsese’s heartfelt adaptation of The Last Temptation of Christ to be “morally offensive.” Scorsese, a devout Catholic, received death threats because information of the film’s content was cherry-picked and spread amongst conservative Christians. Yes, there was a brief scene of Jesus’ buttocks on top of Mary Magdalene, followed by her giving birth, but it was a visage from the Devil to tempt Jesus in renouncing God’s ordainment and living a natural and loving human life; obviously Christ turned it down. Since receiving Silence in a time of his own public persecution and protest, Scorsese has been attempting to make a filmed adaptation of Endō’s book.

28 years later, the Vatican has seen and embraced Scorsese’s Silence. There’s an important distinction there that’s wrapped up in the tidy public-relations push. Scorsese’s adaptation of Silence is about faith, yes, but the larger takeaway is the necessity for religion to adapt to when and where it’s being practiced; that martyrdom was ordained for the Christ and not meant for mortals. Mortals, even priests, need to adapt. This might internalize their personal faith, but that internalization can cut through the silence around them.

The result is one of the most profound films of Martin Scorsese’s career. It conjures a feeling that might be familiar to those who worship or meditate, because Silence is the type of movie that you go to bed respecting but wake up loving. It stirs inside and percolates an intelligent internal conversation.

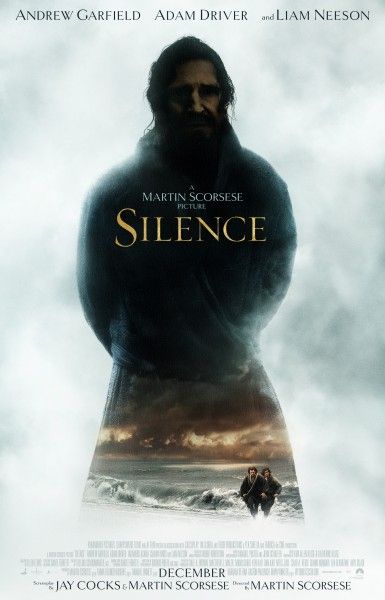

Silence is mostly set in 17th century Japan, but its story begins in Portugal via a whisper from The Netherlands. The entanglement of these three nations is very important to the overall narrative. In Portugal, two young Jesuit priests, Father Rodrigues (Andrew Garfield) and Father Garupe (Adam Driver), have received word from a Dutch trader that their mentor, Father Ferreira (Liam Neeson), had denounced Christ in Japan in order to spare his own life. The last communication from Ferreira was written ten years ago, describing the horrific torture of Christians that he’d seen committed by the Samurai—under direct order from the feudal lords of Japan—to eradicate Christianity from the country.

Rodrigues and Garupe feel that it is their duty to travel to Japan and try to find Ferreira and attempt to save his soul from damnation. They are the last priests sent to Japan during the colonization age. Smuggled through a cave to a small ocean-side village, Rodrigues and Garupe are found by a small group of Japanese Christians who’ve been practicing their faith in solitude. The priests are giving refuge in a shack on the mountain where they hear confession, provide absolution, and cannot venture outside for fear of punishment. Word of their presence spreads and soon Rodrigues and Garupe are traveling to nearby villages to reengage the villagers with the Gospel.

The more visible practice of Christianity makes the villages vulnerable to roundups from the Inquisitor (Issei Ogata). When villagers are rounded up they are forced to apostatize by either stepping on a Christian idol or spitting on the cross. If they cannot, they are publicly tortured and killed. This is where a split between Father Garupe and Father Rodrigues becomes evident. Rodrigues instructs the villagers to save their lives and apostatize, spare their life and practice their faith internally, but Garupe resolutely disagrees. This fracture shows a gradient of adaptation and acceptance in Silence; there’s the unyielding Christian in Garupe, the doubting and malleable Christian in Rodrigues, and the fully assimilated and silent Christian in Ferreira.

Silence is structured very similarly to Terence Malick’s The New World. The first hour has a feeling of a rousing adventure in a new land, the second hour becomes more meditative, and the third act receives a new narrator who observes the changed behavior in our central character (albeit it, more anthropologically and less poetically than Malick’s whispers). And colonization, though presented less fully, has a major imprint on the identity of Silence. The Portuguese were present in Japan to convert the peasants to Christianity and when they were successful they were considered a threat and were purged. The Dutch arrived later, primarily for trade. This itself was an adaptation of relations between new lands.

The adaptation of faith that Rodrigues has to undergo is that his followers embrace martyrdom because self-sacrifice in the face of persecution is a touchstone of Christianity. But in Japan, is it necessary? Rodrigues also wrestles with the worship of his presence in their country, occasionally catching glimpses of Jesus on his own reflection, and whether that means he should spare his followers additional suffering or suffer on their behalf.

There is an extremely interesting power struggle—between martyrdom and order—that’s personified by the Inquisitor and Rodrigues. And in these scenes, Ogata and Garfield have some of the best tête–à–têtes of the year. Importantly, Ogata’s Inquisitor is presented intelligently—with humor and even some moments of grace—as opposed to sniveling and heartless. And Garfield turns in the best performance yet on his current comeback campaign from the ashes of Spider-Man.

The mix of martyrdom and colonization is an immense conversation and Scorsese wisely decides to present both sides and eschew many emotional cues. Instead of utilizing a moving score, the soundtrack mostly enhances the sounds of nature, which is important to both the Christian god and the Buddhist pantheon, and puts the warring spiritualities on a similar plane of earthly existence. And the scenes beside the ocean are filmed with a beautiful foggy immersion that heightens the ambiguity to the necessity of Garupe and Rodrigues’ journey. Silence's cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto utilizes Scorsese’s patented static overhead camera angles perfectly, signifying God’s presence on the steps of the Portuguese church and en route to Japan and then—purposefully—Prieto largely abandons the motif when the priests become spiritually less resolute in their new surroundings.

Silence is a patient film and it’s very much about how Rodrigues’ spiritual journey runs astride nations converging. Universal truths no longer exist in the convergence of cultures. There’s a sadness to that awareness, but faith does become much more personal.

It's obviously very personal for Scorsese, too. The auteur has lived with this narrative in between other projects for nearly three decades, and he's made an astounding passion project. It is beautifully shot, precisely paced, and perfectly acted. There’s even some tragic humor (in Rodrigues’ constant Judas, his untrustworthy and emotionally broken guide, played by Yôsuke Kubozuka). But like any great cinematic journey, the destination only begins to fully reveal itself long after you’ve left the theater.

Grade: A-

Silence opened in select theaters on December 23rd. It expands nationwide on January 13, 2017.