Straddling the line between the golden age of punk in the late 1970s and the prominence of post-punk in the early to mid-1980s, Susan Seidelman’s grungy character study Smithereens brilliantly captures the decline of punk culture in New York City’s East Village through the charming, albeit playfully self-obsessed perspective of the film’s protagonist, Wren (Susan Berman). Following Wren’s bumbling quest to raise money for a trip from New York to Los Angeles upon realizing her disdain for the city’s punk scene, Smithereens boldly captures youthful discontent and the punk movement’s depoliticization through a meandering narrative structure. Filling out the cast with punk icons like rocker-turned-film critic Richard Hell as well as singer and model Kitty Summerall, Seidelman’s intimate grasp of punk sets the film apart as an essential touchstone in the diverse multimedia output of post-punk art. Even after forty years of musical changes and sociocultural shifts, Smithereens remains an honest exhibition of suspended adolescence, punctuated by Seidelman’s unique conception of punk aesthetics through docu-style footage and neorealist storytelling.

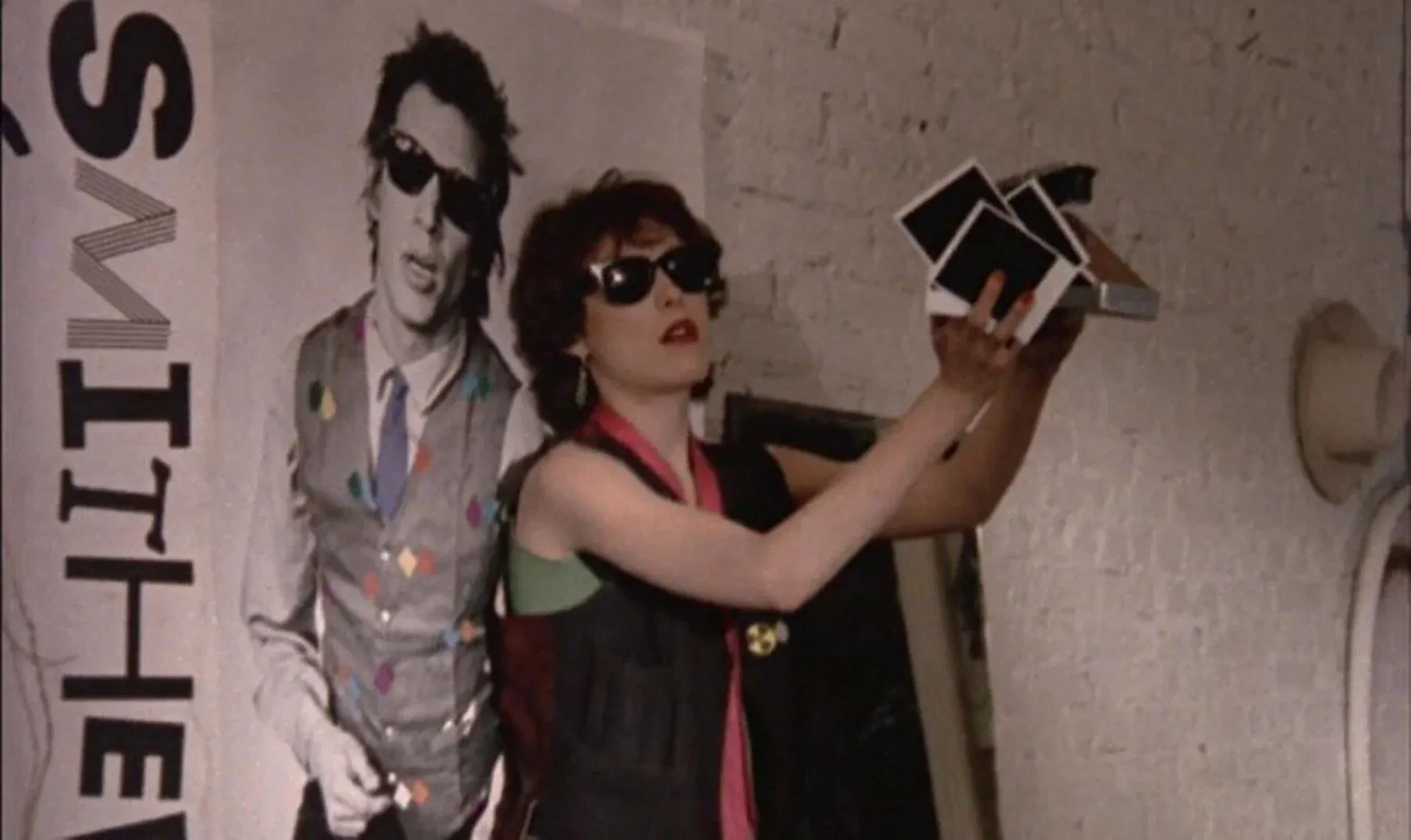

Anchoring the film on a wavelength of rebellious individuality and empathetic frustration, Susan Berman’s protagonist Wren immediately sets herself apart as the last punk standing in the fading East Village scene. Adorned with stolen checkerboard sunglasses, ruby red lipstick, and a stack of self-advertising posters exclaiming “WHO IS THIS?,” Wren makes her dreams of punk notoriety clear from the film’s opening frames, as she ebbs and flows along the subway lines between her day job at a Xerox shop and her nighttime haunts at the once-glorious Peppermint Lounge. The sixteen-millimeter grain of Seidelman’s handheld camera casts Wren in a celluloid atmosphere that mirrors the identity crisis faced by both the nomadic protagonist and the previously punk New York neighborhood in the midst of a personality shift. Rather than emphasizing the city’s grit through spurts of Scorsese-style violence or the intellectual class critiques of Lizzie Borden from the same decade, Seidelman sees the East Village as an externalization of Wren’s wrestling with adolescent self-actualization, folding the protagonist’s punk personality into the artistic spaces and makeshift dwellings that she encounters throughout her time in the city.

While Smithereens announces itself as a fictional account of punk’s last sigh through the eyes of a singular individual, Seidelman’s visual emphasis on documentary-style naturalism situates the filmmaker’s perspective of punk as both a living idea and a fading memory. Even as Seidelman settled into her cinematic aesthetic within the zeitgeist set by Sex Pistols and especially The Ramones, Smithereens allows punk to become personal, empowering Wren’s state of transition to represent a collective unrest with growing out of punk’s gleeful anarchy. By illustrating the unromantic side of punk through Wren’s couch-surfing and sleeping in abandoned vans both for kicks and out of necessity, Smithereens strips away the glamour of the punk movement to highlight the loneliness of a liminal life on the outskirts of adulthood. Rather than foregrounding the sexiness of punk stars like Richard Hell’s conman rock star figure Eric, Seidelman unravels the complexity of the punk lifestyle, rendering the men in Wren’s life as exploitative scroungers and irresponsible cheats; however, rather than forcing both Eric and Paul into a neat category of villainous ex-lovers, Seidelman humanizes the men as desperate and naive punks looking to belong in a manner similar to the central character.

Although Seidelman wisely nuances the characters that populate her impressive debut film, it is impossible to deny the effortless coolness that pervades the soundscape and the visuality throughout the neorealist narrative. Between the reggae-tinged needle drops of The Feelies and the meta-musical interludes by Richard Hell and the Voidoids, the glistening soundtrack throughout Smithereens utilizes punk music to portend the genre’s own demise, playing with the purity of punk rock as a bastion of Wren’s wandering across the city and the nation. From the propulsive percussion of ESG’s “Moody” to doo-wop rhythm of The Nitecaps’ “I Never Felt,” every song adds a layer of personalized texture to Wren’s experience in the underground music scene. Similarly, Seidelman destabilizes the youth-centric coolness of concert venues, crowded clubs, and arcade-adjacent bars to illustrate the slow outgrowth of perceived punk liberation by the young American masses in favor of a more homogenized, and oftentimes suburbanized, existence. Yet even as the film dismantles the effectiveness of punk aesthetics in light of the eighties New Wave, the grit of Seidelman’s vision simultaneously paved the way for the post-punk antics of Alex Cox (Repo Man) and Penelope Spheeris (The Decline of Western Civilization), enshrining the East Village’s punk vistas in celluloid for future generations.

Perhaps the most seismic shift that Smithereens imposed upon the American film industry is Seidelman’s subversion of the studio system through her low-budget storytelling, which helped pave the way for the American independent cinema of the 1990s. Although many auteurs, including David Lynch with Eraserhead and Barbara Loden with Wanda, maximized the creative potential of self-sufficient filmmaking and small-scale financing to create a more personal cinema, Seidelman’s debut stands alongside Jim Jarmusch’s equally meandering and charming portrait of malaise Stranger than Paradise as essential forerunners of the “No Wave” movement as well as the Sundance heyday of the early 1990s. By transposing punk aesthetics into a new form of independent filmmaking, Smithereens helped push cinema into a post-punk space, encouraging other directors to grapple with the ironies of the social implications and political consequences of the raucous late seventies. In the immediate wake of Smithereens, a wide array of multimedia artists including Alex Cox and David Byrne crafted alternative visions of Americana through the sci-fi tinged punk action film Repo Man and the satirical tabloid-centric movie musical True Stories, respectively. Yet even as Emilio Estevez’s glowing green car and John Goodman’s singing cowboy became new signifiers of a movement towards independent filmmaking, the now-iconic image of Wren wearing stolen glasses on a poster exclaiming personal expression and unabashed individuality remains a key symbol of punk’s final days. In a manner similar to Wren’s sudden departure from the grime of New York City for the sunlit glory of Los Angeles, Smithereens stands alone as a singular vision of the final days of American punk, illustrating the beauty of capturing a moment even as it fades away.