The HBO Max miniseries Station Eleven, adapted from the book by Emily St. John Mandel, follows the lives of those who have survived a devastating event: a flu epidemic that directly contributes to the collapse of civilization as they know it. The series, which is created by Patrick Somerville (The Leftovers, Maniac) alternates between past and present timelines to showcase both the pivotal hours leading up to the crisis, the immediate aftermath, and those who have adapted to the new circumstances of their world twenty years later. Technology is mostly a relic of the past, but forms of art — including music and theater — have managed to thrive, and one Shakespearean acting troupe known as the Traveling Symphony ventures from town to town performing for their fellow survivors, but the rise of a cult could also present complications for the group. The sprawling ensemble cast includes both Mackenzie Davis and Matilda Lawler as Kirsten Raymonde at different ages, as well as Himesh Patel as Jeevan Chaudhary, David Wilmot as Clark Thompson, Nabhaan Rizwan as Frank Chaudhary, Daniel Zovatto and Julian Obradors as Tyler Leander, Philippine Velge as Alex, Lori Petty as Sarah, Gael García Bernal as Arthur Leander, Danielle Deadwyler as Miranda Carroll, Caitlin FitzGerald as Elizabeth, and more.

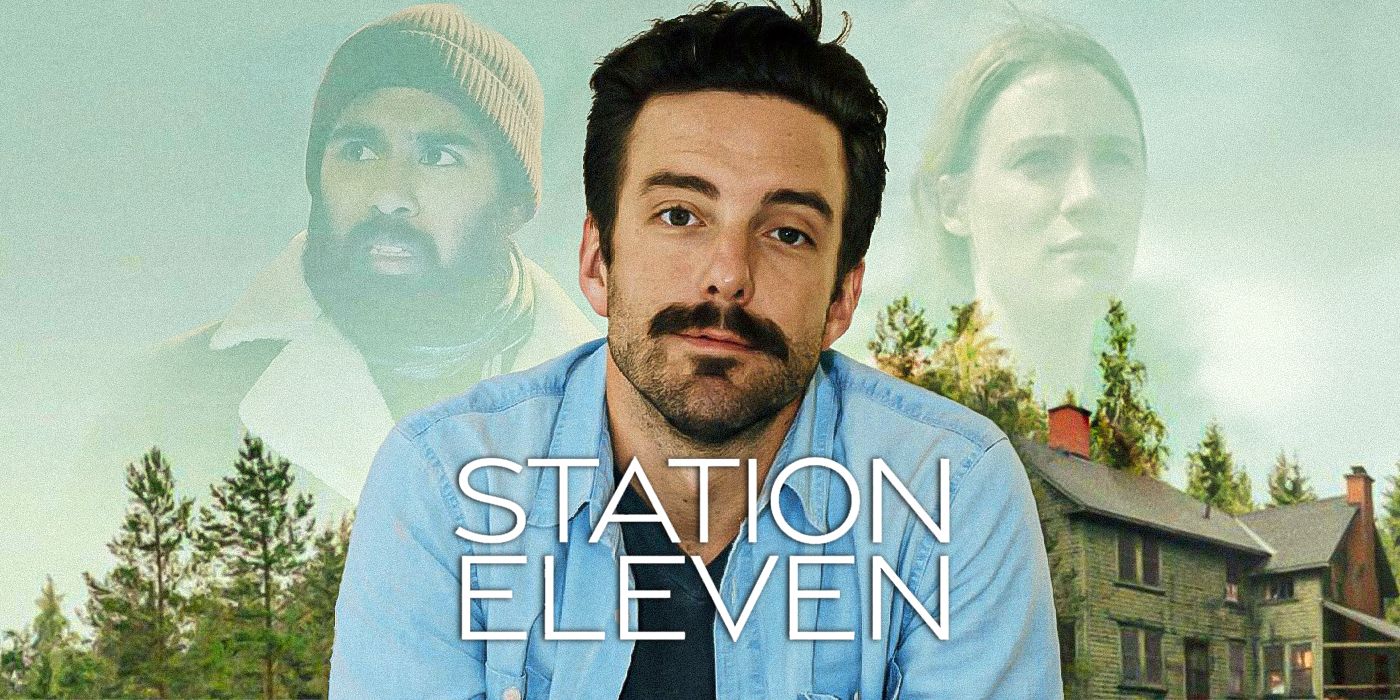

Ahead of the Station Eleven finale, Collider had the opportunity to speak with executive producer Nate Matteson about the HBO Max series. In the interview, which you can read below, Matteson discusses when he and producing partner Hiro Murai, who also serves as director and EP on the show, first came to the project, as well as how Murai crafted the show's distinct visual identity in the pilot episode. He also talks about the surrealness of halting production due to our real-life circumstances, what it was like to eventually return to filming, and what it's been like to see the positive response to the series thus far.

Collider: I would love to go back to the beginning to talk about your involvement. You and Hiro [Murai] have had your production company [Super Frog] for about two years now. When did the two of you first become involved with the project, and what drew you to the story in particular?

NATE MATTESON: Well, yeah, Hiro and I have been working together since 2012 from like an artist and manager relationship. And then we started our company together at top of 2019. I connected Hiro and Patrick [Somerville] for some meetings and chats, I think late 2018. And I don't want to take credit, necessarily, because Patrick obviously was very aware of what Hiro was doing and proactively was trying to find a way to work with him, you know? So I was on the receiving end of calls. But that was, I want to say, like October-ish of 2018, that they began a relationship. And then we started the company in January of 2019 and it was really spring of 2019 that Patrick had reached out specifically about this project. He had been developing it and I think he had already mini-roomed it with a handful of people that he had worked with previously on The Leftovers and some other projects. So he had mapped out kind of what the season was going to be. And we received scripts for Episodes 1 and 2 [then].

It's interesting, sometimes. Hiro surprises even me still where he'll find himself really attracted to or attached to a thing. But he basically just called me and said, "Hey, Pat sent me this project and I've read the first two scripts. And I think there's something really there. Do you want to take a look at it?" What was interesting about it is that in the original drafts, [there] was actually something that we shot. The scenes from Episode 1 where you're getting brought into the world of the Year 20 space, the post-apocalyptic space. There were a pair of travelers kind of wandering through those spaces. And it settled upon them attending a play that was being put on by the Traveling Symphony in the cold open of Episode 1. And we had actually shot some of the travelers still wandering through, [but] we actually used the takes without the travelers. And it just became empty space, of just greenery taking over the stage of where Arthur dies.

So it really evolved, but there's something in that cold open that Pat had originally written where you're settling into these two people like scrapping for copper in a derelict building. [But] then Pat wrote the thing where it's like, "Well, let's not tell their story. Let's settle upon these people who are putting on a play and creating art." And I think that was a thing that sort of hooked Hiro, and by proxy myself, early on.

You started answering my next question already, but it definitely feels like so much of Hiro's direction defines the show's visual identity in that pilot. The brief flashes that we get of Year 20, for example, I know you had said that they were shot one way and then it seems as if they were tweaked in editing. Was there anything else that really came to fruition after the fact versus advanced discussion?

MATTESON: Hiro kind of characterized those flashes of Year 20 as like a rogue radio station breaking into the story of 2020, you know, Year Zero. And we were also just prepping the production and still trying to figure out a little bit of what the language would be of what we called, what Patrick was calling in the scripts, time drifts. Because we knew that the project was going to really play over obviously over the course of many, many years. The story, I think, takes place over something like 35 years or more. And we knew that in order to do that, we wanted to play with different visual languages to establish how the audience was going to be understanding how we were going to whip through time.

Because you didn't really want to do that thing everyone is super familiar with, where the past is color bleached out and the present is lush in color. Cinematic languages that we're overly familiar with to explain time gaps. So Patrick just sort of wrote this thing in that was like, "We don't know what it's going to be yet, but we're calling it a time drift right now." And what we were talking about in those early days was that maybe each episode has a different version of what we mean by time drift. That kind of held true.

There's a moment, for example, in Episode 3, where Miranda boards an elevator in 2020 and then gets off of the elevator onto a city street in 2005. And that was achieved through some cinematic trickery. And that was something that we were playing with in Episode 3. The camera moves and we thought we were in one time period, and now we're in another time period. There were some fun Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind tricks to do that. But ultimately, Hiro just shot [the Episode 1 flashes] both ways, or thought, "Well, let's just lock the camera down and watch a scene, of again, just [the] empty auditorium that's overgrown, and see what that looks like. Just like the stillness of that." And I think that, for him and Patrick, made more sense. To settle on the stillness since that episode is so kinetic and adrenaline-fueled, the outbreak happening and Jeevan and Kirsten trying to get to safety. It's almost like a little bit of a chase movie, of them trying to escape this thing. And so I think the stillness probably just spoke to him in a way of breaking up that energy.

Talking about the before and the after, there are ways in which the production of the show kind of mimicked our own reality that I don't think were initially anticipated. I know there was a period where you all had to shut down for a while and you were still all working on the show during lockdown. When I spoke to Patrick and Jessica [Rhoades], they said there was this surreal feeling of everyone being back and that it almost felt that they were in the world of the show. So I was wondering what your experience was like, and if that held true for you.

MATTESON: Yeah. It was all very odd. And obviously all the other feelings too, very scary and sad. But there was also something so disassociating about different parts of making this thing, just given the crossover of art and reality. I was physically most present during the first block of shooting, which is Episodes 1 and 3, which we shot over the course of January and February primarily in Chicago and a little bit outside of LA. And Arthur's house is shot in Chatsworth, the pretty famous house and pretty famous location, which is where we ended that block. So our last few days, we spent most of January and a good chunk of February just battling the cold of Chicago. And then came back to LA to finish the last few days. And then the whole thing moved into post.

But of course, along the way, even while we were in Chicago... One of the more surreal days actually was when we were shooting the scene of Siya [Chaudhary] and the other folks in the hospital, just outside the hospital. We shot in a public building that was made to look like the exterior of an emergency room being overrun. I have a photo on my phone of two extras in hazmat suits, with Hiro and Patrick standing on either side of them. And literally, at the same time, we were looking at alerts on our phone about the outbreak in Wuhan. And then it wasn't until really we were moving into post where the first cases were really hitting in a big way stateside. And then we shut down post-production and moved the edit into the editors' homes in mid-March when the cities were shutting down.

Our original intention obviously was to shut down. We had already had a planned stop down. We wanted to cut Episodes 1 and 3 and learn something from the post-production process before moving into getting back and going in the Chicago area, in what would've been probably like late April, May of 2020. And of course, that didn't happen. So when it all got back and up on its feet outside of Toronto, I actually didn't join the production. I was here in LA. And Jessica was the only non-writing producer, really, boots on the ground at that point. Which was in part by design too. Hiro and I had a lot of other things to work on. He was getting back into Atlanta and I was getting another show going, with this project called The Bear. So I had to focus some of my attention on that. For me, the experience was just very strange. I was still working on the show, but I felt like I was a little bit on like a satellite, to some degree. Trying to have input and provide support quite remotely. Watching dailies every morning from the comfort of my couch, you know? So it was a different version of surreal, I think.

What's it been like for you to see the response to the show as people are watching this every week, especially considering not only our current situation but also the fact that some people might balk at hearing what the show is about but giving it a chance anyway?

MATTESON: Yeah. Yeah, it's a real mixture of emotion. Thanks for asking that question. There's a few things that kind of come to mind. My own emotional action has just been one of feeling my heart very much warmed by the whole experience. Feeling, again, both complete delight over the fact that it's been received as it has, and all also a mixture of melancholy given the circumstance of why people are going to it, to process it in the way that they have.

I also think that a lot of the bones and the architecture of the story are exactly as they were intended, even before the pandemic happened. But there were just layers of depth and personal experience that then informed the product as it was continually being written and in production. I think everybody from, all the cast and all the crew, and so then all the producers and writers, were bringing their own personal experience to the subtext of what the thing was going to be. Which just made it even, obviously much richer than it ever would've been, had art and reality not sort of mimicked each other.

We knew from the point at which production shut down and the reasons why production shut down, that when this thing finally came out, there were going to be folks that wouldn't be ready to watch it. And we were ultimately okay with that. Very okay with that. My grandfather fought in World War II. And I remember asking him if he wanted to go watch Saving Private Ryan when that came out. And he was like, "I don't have any need to watch that movie." And I would imagine there's a lot of folks that think, "I experienced like a hard version of this thing. I don't necessarily need to confront it in fiction." But I think there's also just as many, if not more, people that want to go to this kind of storytelling as a form of processing their own experience. And again, I guess I'm grateful to be a small part in creating a vessel for folks to process something that they went through. I've come to a Zen place of knowing that the work is serving a really good function out there in the world.

Station Eleven is currently available to stream on HBO Max.