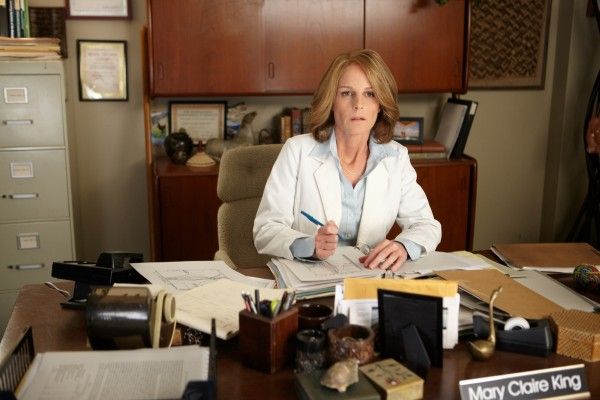

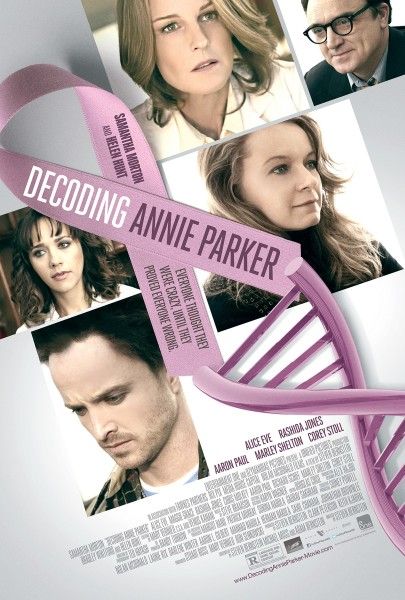

Opening in limited release on May 2nd, Decoding Annie Parker is a life affirming story told with grace and humor about two remarkable women who wage a courageous 15-year battle against breast cancer on both scientific and emotional fronts. Geneticist Mary-Claire King (Helen Hunt) is convinced there’s a link between DNA and cancer and makes one of the most important genetic discoveries of the 20th century, while irrepressible cancer survivor Annie Parker (Samantha Morton) struggles to hold her family and life together with dignity and courage even as her body betrays her. Directed by Steven Bernstein from a screenplay co-written with Adam Bernstein and Michael Moss, the inspiring indie drama based on true events also stars Aaron Paul, Maggie Grace, Alice Eve, Rashida Jones, Marley Shelton, Corey Stoll, Ben McKenzie and Richard Schiff.

In an exclusive interview, Bernstein talked about why he believed deeply in the subject matter he chose for his feature directorial debut, what makes King and Parker remarkable women, what the cast brought to their roles, how winning the Sloan award validated a type of filmmaking that truly matters to him, his experience being a first-time director, the contributions of his creative team, the influence of directors Mike Leigh and John Cassavetes, the film’s byzantine financing and unusual distribution strategy, and his upcoming movie, Dominion, about Dylan Thomas starring Rhys Ifans, John Malkovich, Tony Hale and Zosia Mamet. Check out the interview after the jump.

QUESTION: I found your film very engaging and entertaining even as it’s tackling a very serious subject. Can you talk a little bit about how the project emerged? What inspired you to write this and did you always plan to direct?

STEVEN BERNSTEIN: I had always planned to direct. In fact, the original plan was to be a director. I had some small successes as a cinematographer early on, and then you know how life goes, you suddenly find yourself going down a path. I was writing all the time. I was living in England at this time and doing a lot of theater and doing small plays. I wrote a book about film, but kept not directing over time. And then finally, I shot a film called Monster with Charlize Theron and then the producer of that, Clark Peterson, said, “Steven, you’ve worked for so many first-time directors, you really should direct. You write anyway. Just find some material that is of interest to you.” My preoccupation has always been with people who are suffering, not because I have a dark spirit particularly, but because I think that it points the way to those things that we find most valuable. I was looking for a sense of primal self that we look at things and discover what’s significant, and I thought people in crisis make that examination and discover ultimately what’s really important. I began looking for that story. My sister sadly passed this past year of cancer. My mother had died the year before that and my dad the year before that. I had become preoccupied particularly with people who were terminally ill and came across Annie Parker’s story when looking around for a story that I might make into a film. I took elements of her story, combined it with elements of other people who I had known that had cancer, came across Mary-Claire King’s story, this heroic woman who had fought for so long on so many different issues, and just thought, “Is there a common thread to all of these people’s lives?” To me, it was this element of faith with a small “f”, the idea that if you believe in something, anything, that somehow it can sustain you. It becomes this affirmation of life. It’s a conscious decision that we make and somehow this will propel us through insuperable obstacles. In Mary-Claire King’s case, it was no one believing in anything she said and having no financial support. In Annie Parker’s case, it was having cancer three times. But to me, the thread that unified the two stories was this state that somehow they would survive, persevere and triumph, and in these particular instances, both did.

It’s been 24 years since Dr. King identified the BRCA1 gene mutation in 1990. What are your thoughts on her contributions and the impact of her discovery?

BERNSTEIN: It’s absolutely fascinating and it’s changed the world. It’s so frustrating for me that no one knows who she is and I can’t figure that out. I can’t understand the reason for it. The significance of this discovery is just beyond all measure. She does this important research and she announces it. And this is the wonderful paradox of it all: She goes to read her paper in Cincinnati where there’s this juxtaposition of the profound and the banal. The World Series is going on at the same time. I swear to you this is the truth. While she’s reading this seminal paper that will forever change our understanding of disease and recognizing this genetic component to all types of cancer essentially, sometimes what she’s saying is being drowned out by the cheers coming from what was really important to people, which is the World Series two blocks away. I wish I’d put that scene in the film, but it’s just too hard to believe.

What makes Annie Parker noteworthy?

BERNSTEIN: That’s a really good question. I love her. She’s a dear friend of mine. To me, what makes her noteworthy is that she is just like all of us. This is the sweetest woman. She is xenophobic. She is parochial. She rarely leaves Toronto. Her greatest moment, which I adored, was when there was an article in her local Brampton newspaper that had a picture of her on the front cover. That’s how centered she is. This is a girl who left school when she was still in high school, married very young, had a baby very young. What’s extraordinary about her is that there is nothing extraordinary. She’s just an ordinary person with this profound depth of spirit that keeps her going. She went on tour with me with the film because I tried to roll the film out first through charities. I thought why don’t we try to raise money for charities with a film that’s about something important and see what we can do. My financial partner said films don’t work that way. You won’t raise any money, but we raised $1.5 million for breast cancer research, which is kind of cool, and she came with me the entire time. Like any Jewish filmmaker, I whined and complained all the time. “I’m so tired. I feel so uncomfortable being interviewed because I’m a shy person.” She never complained once. She just said, “Isn’t this fantastic? What a great adventure this is.” I realized there is the embodiment of a remarkable spirit. She may not be famous. She may not be a Nobel Prize Laureate, but she is one of these unique people who can find this energy within her to be positive in all circumstances. From what her doctors told me, all through her cancer it was the same thing -- a sunny disposition after chemotherapy. It is a remarkable spirit, and to my mind, not to sound too New Age, but a life lesson for all of us about how we might conduct our interactions with a sometimes cruel world.

What did it mean to you to win the Sloan Feature Film Prize which is designed to encourage filmmakers to create more realistic and accurate stories about science and technology and to challenge existing stereotypes about scientists and engineers in the popular imagination?"

BERNSTEIN: To me, it was hugely significant. It’s not an Oscar and I appreciate that, but this film took seven years of my life to get to the screen. Seven years. We ran out of money constantly. I was going all around the world begging people to invest in the movie. It came from all non-traditional sources of finance. I raised the money before I had any actress in it. We ran out of money in post-production. People kept telling me, “Drop it. Send it to television. Let it go. Make it a Lifetime movie.” And no disrespect for Lifetime, but I said, “No, no. I think this is important, and I may not be an important person, but maybe the film may be more important than I am.” At the end of all that, to finally get some sort of validation was important for me as a filmmaker and as a writer.

The other significant thing, and what’s important to me, was that the film is a middle ground between complicated science which I tried to make accessible and an ordinary human story of great suffering and courage. I tried to find that happy balance, and I thought maybe this was a way forward in the future as well. I can make a film without important ideas or about science, or my next film which I start shooting in three weeks which is about Dylan Thomas and alcoholism. I can do films about important subjects that are still accessible to audiences, and people can want to go see it and enjoy it as a film, but it can be about something besides a comedy or action or adventure. So, that’s what it was to me. It was a sort of validation of a type of filmmaking that said, “Make a film about something important, but still make it entertaining.” It said to me that I achieved that. Whether I did or not, I don’t know. You’re a better judge than I. I got to a time where I want to do films about the stuff that counts and to be able to do that and still find an audience.

Can you talk a little about the film’s unusual distribution strategy?

BERNSTEIN: We’ve been doing this radical rollout now where not only did we do the charity films which were great, but now we’re doing this combination of releasing the film theatrically via e-One Films, and then also there’s this little company called Gather that does individual screenings. We’ve got 50 individual screenings all happening across the country at the beginning of May while at the same the film is being released commercially. It’s like private screenings for groups. I don’t know if it will work, but again I’m kind of a radical model and what we’ve been doing all along is getting this film out there. That’s what we’re trying to do with all these cancer groups. We’re in touch with a group called Of Course that we worked with. We did five screenings with them during the charity rollout. They were helping us find an audience. There’s a group called Sharsheret which just works with Ashkenazi women who have a predisposition to breast cancer. They’re helping. And there’s a group called Cancer Care and the ACLU. It’s a radical way to approach film distribution. I don’t know if it will work. We seem to be getting a little bit of attention, but I won’t know until May 2nd whether I succeeded or failed. With the Sloan Award at least people are recognizing that I made a noble attempt to make a film about something that mattered, and I hope I find an audience.

What did Helen Hunt, Samantha Morton, Aaron Paul and the rest of the cast bring to the film?

BERNSTEIN: I’ve been a cinematographer for a long time, and there are sets that are happy and there are sets that aren’t happy. It was my first movie and I was of course terrified. I thought, “Oh my God, what have I done? These are people bigger than I am. I’m a first-time director. They’re going to eat me up.” And the opposite happened. We went out to a place called the Fred C. Nelles Youth Correctional Facility. It’s a youth detention center in Whittier, California. We took it over. The State gave it to us for free if we cut the grass and knocked down the hornets’ nest. We lived on that campus. Helen, Samantha and Aaron all came out there and we all more or less just stayed together making this film. I would say in 35 years of working on film sets, and it wasn’t just because I was directing, it was the best experience I had with human beings in all that time. People were feeling that they were doing something important. They cared about each other and they were very nurturing to me in particular. Aaron is the nicest person I think I’ve ever met in the film industry. He really is as nice as they make him out to be. Helen was instructive, kind and patient. Samantha brought a passion to the role. How she survived pretending to be going through chemo, and she is essentially a Method actress, it was painful to watch the intensity that she brought to it. All of us working together was magical. Rashida Jones and Richard Schiff and it goes on and on. I don’t know if I’ll ever have an experience like it again, but it was magical.

What was it like directing your first feature film? Were there any surprises? What did you learn?

BERNSTEIN: I felt like the Twelve-Step Program where they want you to go back and apologize to anybody you have ever hurt. As a cinematographer, I felt like going back to every director I ever worked for and saying, “I’m sorry I was such an arrogant bugger.” I had no idea how hard it was and how many things you have to be concerned with, and then ultimately that sense of final responsibility, that if you get it wrong, there’s nobody there to fix it for you. You’re the final arbiter and it was terrifying. You’re certain throughout that the thing is going to fail and that it’s not working. There’s a constant uncertainty because there’s nobody else there to protect you. The thing about cinematographers, what’s important to a cinematographer’s job is ultimately you can still walk away and say, “Well, the director blew it.” But if you’re the director, who are you going to blame? That was a difficult thing, I think.

On the financial side, I had no idea how arcane or convoluted or I should say byzantine finances are, particularly in release and post-production. The lawyers are probably more important than the filmmakers are. I had no idea. That was painful. And then, distribution, how difficult distribution was. So, the whole business side of it can be very soul-destroying. What I discovered was if the film hadn’t been about something important, I just would have given up. I don’t know how anyone suffers as one has to suffer to make a film and not believe deeply in the subject matter, so that’s what I learned.

Was it hard to find the right tone when you’re dealing with serious subject matter like this, and yet bring a sense of humor and humanity that makes it accessible to an audience?

BERNSTEIN: I’ve had individual tragedies, and of course, we all have. I went through it with my parents. There are things that we seek in life and things that we seek to avoid. The things that we seek in life are things like humor and love. We romanticize love and we ridicule oddly humor as if it’s somehow insignificant, but we seek it out in our lives all the time. To me, there is a profoundness in comedy and an irony. It is the embracing of life. So I can’t imagine ever [being without it]. Even with the new Dylan Thomas film about a guy who’s drinking himself to death, it’s still full of humor. My experience with my parent when they were ill, there was still great comedy in the experiences that one has. It doesn’t mean that you don’t feel deeply. It doesn’t mean you don’t love the person who was ill or dying or infirmed, but the nature of life is that it’s full of irony and comic moments and we embrace those. If we recognize that in our characters, that this is what we all seek, that we want to laugh and we don’t want to cry, that tragedy is inevitable, then I think these two things naturally juxtapose. When people try to do serious films about serious subjects, they’re denying the real nature of themselves and of the world.

Can you talk about the contributions of your creative team?

BERNSTEIN: We had Doug Crise who was the editor who worked on Babel and other films. He was kind of a brother/father figure to me and guided me through the post-production. [It was great] to have a really brilliant editor when we had so much material because I’m much influenced by the director Mike Leigh. We would integrate improvisation with the actual script, so I would have a lot of material. Having a great editor was hugely important to me. Ted Hayash, the cinematographer, was my long term gaffer, so we had a relationship that went back 20 years. It was the same thing with the camera operator, Mike Ferris, who was John Cassavetes’ camera operator. I draw very heavily from Cassavetes as well. So, to have Mike Ferris there telling me the way Cassavetes might have done something was really great, profound and significant. And then, the actors most of all felt very protective of me and combined together to constantly provide me with support. It was a 20-day shoot so it was hugely difficult, but people like Rashida Jones and Corey Stoll and Alice Eve would hang around set and hang around the location just to help out. Having that level of support from so many actors was hugely important to me. It empowered me and made the thing more successful than it might have otherwise been.

How did the musical choices in the film complement the story?

BERNSTEIN: The film is about an affirmation of life. That’s one of the themes. When I think back to the 60’s and 70’s, I remember my happiest days were with some very poppy, life-affirming music. I tried to make the music parallel the themes of the film. So, when I picked The Turtles, I don’t think The Turtles would ever be considered some of the great poets of our generation, but the music was infectious. It reflected the innocence of the characters. The character played by Aaron Paul is the perpetual child, the guy who wants to be the rocker but never quite is willing to accept the ordinary realities of the banal and cruel world. His theme or leitmotif is always this pop music because he interacts with the world in a poppy way. Samantha plays a more serious role. When she confronts cancer, her view of the world alters and she develops a more mature and adult sensibility. Steve Bramson who is our brilliant composer composed this fantastic soundtrack that would track Annie’s journey. She goes from pop music to something serious and operatic and more profound, because my view is when you confront serious illness, and when you confront death, and when you go through personal tragedy, you evolve into a different person than someone who doesn’t have the benefit of those tragedies. I think tragedy brings us maturity and so sometimes it’s sort of a blessing.

How does the final film compare to what you originally envisioned?

BERNSTEIN: The first script was written by my son, Adam and I, which is kind of unusual for a father and son to write a script together. A lot of the humor has remained intact. A lot of the dialogue remained intact, but some of it went away. The overall structure remained very similar. We found that we wanted to create a more ostensible relationship between Mary-Claire King and Annie. Initially, I was philosophically pure and just said, “These are two different stories that have the same theme, and the audience will unify them naturally because they’ll recognize the thematic similarities.” When we first showed the film to families and friends, nobody quite got the relationship between the two stories. I discovered I had to keep going back and creating this relationship, even faking some things I hadn’t originally filmed, like putting letters in between the two characters. They never in fact met in real life. I made that up, but I felt I had to do it because otherwise the two stories would seem too disparate. Philosophically, I wanted to suggest that logically they should have met because they were both on two different journeys, but they learned the same lessons even though they were on different journeys. That’s why I had them meet at the end. What was cool was when I showed the film in Seattle near Dr. King’s lab, the two of them actually met in real life, and that was probably the most emotional experience of the past seven years, except for the passing of my family, which was to see the two of them on stage finally meeting for the first time. We had a standing ovation in Seattle at the Seattle Film Festival, and Samantha then went on to win the Best Actress award. Seattle was a remarkable experience. I cried a little bit I have to say.

Have both Dr. King and Annie Parker seen the film and what was their reaction?

BERNSTEIN: Yes. There was a great moment just before I showed the film in New York. I had sent the film to Dr. King because I wanted her to be the first to see it. I didn’t hear from her because I was traveling and she was traveling. She finally saw it literally the day of the premiere. She sent me a text message, which sounds filmic but it’s true, on the way to the premiere in New York. She said, “I loved your film. I think it’s important. Annie Parker is my new hero.” I read that to the crowd and that was a huge emotional moment for me. Annie Parker toured the country with me and the film so she has seen it probably 70 times now. She constantly laughs at the parts that she knows I made up, and she corrects me on some parts, like where there’s a scene where she’s having sex. She still feels very uncomfortable with that because her child will see it. She’s seen it a lot and is still a champion of the film, and now she’s written a book based on her experience with the film and her experience before the film. We’re now looking for a publisher. We’re trying to get it out this summer.

You mentioned the importance of making films that really matter. As a filmmaker, what impact do you hope this film will have?

BERNSTEIN: I think it’s an affirmation of life. I have found that a large part of my life was very difficult and painful, and then somehow as I began to change my view of it, I began to enjoy life more. If Annie Parker and Dr. King have a lesson for us, it’s this: Life is by its nature difficult, but if we can alter our spirits and our attitudes towards it, we can survive. It doesn’t sound like a very profound lesson. It’s probably much clichéd because people say it all the time, but Annie Parker is witness to it. This is the most life-loving individual I’ve ever met. Every moment has this sense of joie de vivre and this is a person who’s been through cancer three times. If a person who has looked in the face of death and loves every single moment of life, can never be negative, never argues, and enjoys even the smallest thing, then surely that’s the most profound lesson for all of us. I think we avoid these experiences, but when we have them, they alter us. They’re profound. When I saw my parents suffering, I thought “Oh my God,” but then ultimately it alters the way I live my life.

What are you working on next that you’re excited for audiences to see?

BERNSTEIN: The one I’m doing now is Dominion. I’m in Montreal right now. We’re in the final stages of pre-production. It’s about the last days of Dylan Thomas drinking himself to death in the White Horse Tavern. It’s got Rhys Ifans playing Dylan Thomas. We have John Malkovich playing his foil. Tony Hale is playing his best friend. Zosia Mamet is playing the girl that stalks him. It’s a great cast. Again, it’s another sad subject matter about alcoholism and the artist, but I somehow found financing again for another low budget film about something that matters. Also, I’ve been commissioned to write a screenplay about a romantic comedy in Greece, but that too is about people deciding to radically change their lives. A bunch of people go to Greece and think they’re going there to make a business development and then realize there are more important things than money and abject commercialism. And then, after that, I have a screenplay I wrote a long time ago about the north of India. It’s sort of a follow-up to The Man Who Would Be King which is my big epic piece, but it’s more about India than anything else. And then, the other screenplay I’m developing is about the Crimea War and the early medical care that was available then. As I began to study all the medicine around Dr. King, I became very interested in the history of medicine and then the early uses of anesthetic and disinfectants. In the order of those films, that’s probably the next one that’s going to get made. The next one that’s going to get written is the one about Greece, but I think the next one that gets made is the film about the Crimea. All of these are in development and I haven’t given them any names yet.