The Stonewall Riots are one of the most important events in the history of U.S. civil rights. It was a watershed moment for the gay community, but unfortunately for director Roland Emmerich, they’re nothing more than a platform for him to tell a meandering, clichéd, messy story about young, homeless gay men living in 1969 New York City. Emmerich’s intent—to shine a light on the “unsung heroes” of the time may be well intentioned, but the execution is so shoddy as to become borderline offensive and outright careless. Stonewall is so much smaller than its namesake implies, and it’s an insult to the larger historical narrative.

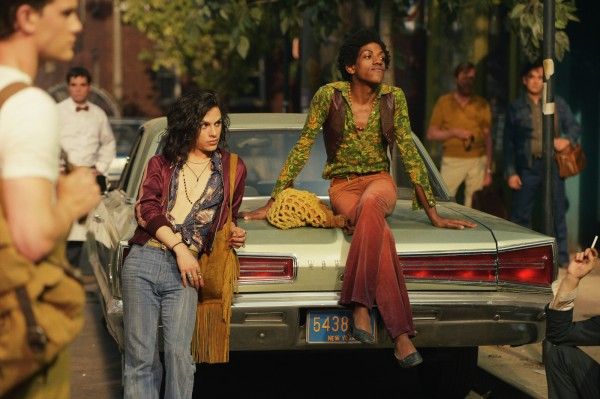

Taking place in the months before the June 1969 Stonewall Riots, the story begins when Danny (Jeremy Irvine), a gay teen from an idyllic small town in Indiana, moves to 7th Avenue and Christopher Street, the heart of New York City’s gay community. Although Danny is due to enroll in Columbia in the fall, he currently has no home, income, or friends, but he’s quickly joins up with Ray (Jonny Beauchamp) who are also gay and homeless. From there, the story putters about at it tries to find a way to give the milquetoast Danny an interesting storyline while also including notable figures from the setting, but not making them vitally important to the overall story.

The Stonewall Riots don’t really even begin until the film is almost twenty-five minutes over, and they occupy about 10-15 minutes of the total runtime. They’re not Emmerich’s primary interest, and instead just provide a loose framework for telling a story about homeless gay youth and how they’re usually forced into prostitution to survive. Emmerich could have just as easily set this film in the present day—as the end titles tell us, a large portion of the U.S. homeless population is comprised of gay youth—but he wants to trade in on the history without actually doing the legwork of delving into the complexities of the time period.

Jon Robin Baitz’s script briefly flirts with the civil rights aspect—namely, is assimilation and patience the best way forward or is it through open rebellion—but Emmerich doesn’t have the patience or the thoughtfulness to pursue this kind of intellectual drama. Everything’s winnowed down to stock characters whose plight is reduced down to an average. I believe people like Danny and Ray existed, but there’s no individuality to these characters; they’re gay stereotypes meant to carry a banner to the point where Danny literally shouts “Gay power!” before throwing a brick through a window.

Setting aside the uncomfortable racial aspect of this scene (a black character hands the brick over to the white character rather than taking agency in the scene), there’s no room for nuance in Emmerich’s film. While his previous drama, Anonymous, was fine, Stonewall shows that he lacks the maturity for this kind of subject matter despite having his heart in the right place. There’s a lot of empathy for Danny, and yet there’s no specificity for him or his friends, which in turns creates an odd sort of callousness. For Emmerich, homeless gay teens spend their days either hooking or talking about how much they love Judy Garland. It’s disappointing that Emmerich, who is gay, would want to feature stereotypes so heavily in his movie and move away from a film that could actually inspire gay and straight viewers alike.

Instead, despite the fact that homeless gay youth is a current issue, Stonewall feels dated and distant. The production design makes the movie look cheap; everything is bathed in a golden glow for some reason; and almost all of the performances are painfully overwrought. Stonewall wants you to know that it’s A Very Important Movie™, but doesn’t want to put in any of the work at the narrative or character level, which is how you get stereotypes talking in awful dialogue and ignoring a seminal moment of American history.

I hope that one day a director does justice to what happened at Stonewall and all the players involved, and that they do so in a manner that acknowledges the great diversity at play. Emmerich’s attempt to celebrate the unsung heroes, however well intentioned, feels like an unintentional slight to those who played a pivotal role, and while Stonewall may want to cast a light on struggling gay youth, his movie could have helped more by showing homosexual and transgender people in an active, positive light rather than a watered-down story that reduces everyone to clichés and footnotes.

Rating: D-