[Editor’s Note: Welcome to “Stream This,” our weekly feature where we single out television programs and movies of considerable merit that are available on Netflix, Hulu, Amazon, Crackle, or other streaming services.]

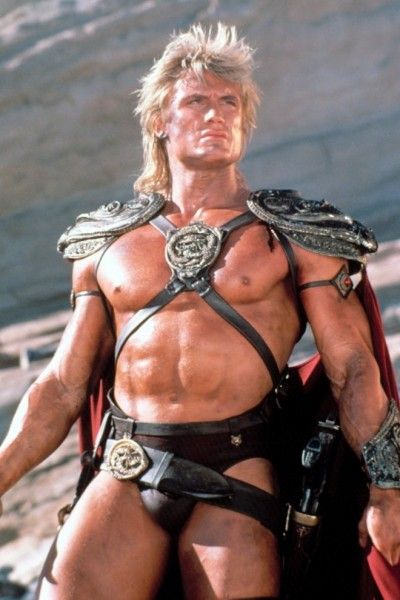

Even if you're not much of a cinephile, there's a tremendous likelihood that you've stumbled across a Cannon Films joint. They're the company chiefly responsible for some of the most truly bizarre sequels and one-off adaptations that have ever made it to the big screen. That Superman film where he fights an atomic Chippendale dancer and hucks a net full of nuclear weapons into the sun without repercussion? That's Cannon. All those increasingly sadistic and aesthetically noxious Death Wish films following the gritty, not-half-bad original? That's Cannon. That inexplicable He-Man adaptation where the dwarf-creature blows his ear wax all over everyone and Frank Langella looks akin to an elderly Descent creature? Cannon.

In Electric Boogaloo: The Wild, Untold Story of Cannon Films, the filmmaker Mark Hartley, working with unlikely producer Brett Ratner, traces the humble beginnings of the production company, which came into prominence under the team of Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus in the late 1970s, up until the pair's exit from the company in early-to-mid 1990s. The thrust of Hartley's documentary is not unlike the trashy behind-the-scenes Hollywood exposes that were so popular in the 1960s and 70s - think Kenneth Angers' Hollywood Babylon for the 1980s, yet somehow a bit more redeeming. Golan and Globus are not depicted here as abhorrent perverts or drug addicts, but rather junkies of a totally different sort - men strung out on the business of producing, selling, and marketing movies. That this particular hunger, need even, brought on morally questionable behavior, and simply grotesque acts, is a distinction that's worth making.

Hartley doesn't get too much into the early days of Golan and Globus, Israeli cousins who dreamed of taking over Hollywood, which is perhaps the sole slight in this kinetic journey. They were big-time wheelers and dealers in the Israeli movie business, with Golan having directed a number of pictures and Globus having a preternatural sense of how to secure and account for money in production budgets. In America, after they took over Cannon from its original owners, who had not done much more than make and release the beloved, Peter Boyle-led political oddity Joe, Golan and Globus started making B-movies, exploitation flicks, and other small-scale pictures that could be sold on the quick to major (and minor) distributors.

From this point on, Electric Boogaloo grows into a startlingly fast-paced account of both the movies that were made, a smattering of gossip about how Cannon's films were made, and how Cannon was run by the eccentric duo. Dolph Lundgren admits that he felt "stupid" about making Masters of the Universe, while a handful of writers discuss the dreadful rewrites and cuts they suffered at the hands of Golan specifically. Elsewhere, several people, including Bill & Ted's Excellent Adventure star Alex Winter, speak of the sadistic practices and artless hackery of Michael Winner, the notorious director of the first three Death Wish films, and Bo Derek recounts a shocking tale of her work with Cannon and Golan on Bolero. The stories pile up, and Hartley smartly cuts quickly between a dense variety of workers, including music supervisors, producers of all sorts, and production designers, giving the entire film the feeling of a friendly gathering of colleagues at a bar talking about their employer with equal parts disgust and fondness.

Hartley eventually tracks Cannon to the point of financial ruin, after their decision to go from making cheap movies, waiting for one of them to be a hit, and then using the proceeds to help make more movies. Early on in the film, both archival footage of Golan and interviews with their colleagues, or employees, make a point of harping on the fact that Golan and Globus wanted as much money as possible to go into the movies, rather than schmoozing or bankrolling their own would-be opulence. In essence, Hartley is telling a cautionary tale to modern movie studios, who have gone from making more modestly budgeted pictures with a handful of tentpole movies to making almost no films that cost less than ten-million dollars and rather stressing films that cost well over one-hundred million dollars. As plenty of movie-finance obsessives have pointed out, this situation is untenable, and a few major flops in a row could lead to a major motion picture studio sinking. Electric Boogaloo both illustrates how desperation and greed leads to this, and how deliriously addictive making movies can be, even when they're films as dreadful as The Texas Chainsaw Masscare 2 and the simply unforgivable Invasion U.S.A..

There's a strain in Electric Boogaloo that finds more joy in movies that are so bad they're good, which is both forgivable and a bit dubious, but the film ultimately makes a point of highlighting the fact that Cannon was responsible for producing some of the most radical masterworks of the 1980s. After all, this was the company that allowed John Cassavettes to make Love Streams, which is perhaps the most daring work of the American auteur's trailblazing ouevre, and there are no words for the kind of strange, ambitious, and deeply critical madness that Jean-Luc Godard was able to unleash with King Lear, his infamous experimental Shakespeare adaptation that includes phone message from a frazzled Golan. Beyond that, there's Runaway Train, arguably the most staggeringly poetic action film that's ever been made, and Barbet Schroeder's,er, intoxicating Barfly, the only film that's ever convincingly conveyed the world of Charles Bukowski.

Jerry Schatzberg's Street Smart and Tobe Hooper's rapturously bizarre Lifeforce belong on a similarly elevated tier in the annals of American films of the 1980s, and these directors found a cozy home at Cannon. John Frankenheimer, Robert Altman, and Franco Zeffirelli also made films with Cannon, and had Golan and Globus had a better eye for directors, they might have gone down as one of the most artistically liberating production companies in the history of the cinema. As it stands, they are notorious for the kinds of films they allowed to be made, and the lengths they went to in their forge to aggressively market these films, but Hartley final point seems to be that notoriety is a far better thing than the unending mediocrities that now typify most studios.

Electric Boogaloo: The Wild, Untold Story of Cannon Films is currently available to stream on Netflix. Check back soon for a new Stream This!