The Big Picture

- Studio Ghibli's unique style and thematic exploration set it apart from other animators, with a focus on natural settings and independent female heroes.

- Miyazaki's films blend Western stories with Japanese folklore, emphasizing magical realism, environmentalism, and the sublimity of nature.

- Ponyo, Howl's Moving Castle, and Spirited Away are retellings of Western fairytales, infused with Miyazaki's whimsical touch and his exploration of complex themes.

Fairy tales have long captured the imaginations of animators both in the Western and Japanese film industries, providing a unique avenue to explore fantastical heroes, menacing villains, and moral dilemmas. However, Studio Ghibli remains distinct in style and thematic exploration, with each film resembling a series of vividly detailed paintings as the focus on natural settings remains eminent. Blending Western stories with Japanese folklore, Hayao Miyazaki imbues his films with his sensibilities that illustrate his fascination with magical realism, child-like wonder, and the sublimity of nature. Independent female heroes are often the focal point of Miyazaki’s films, rather than turning them into victims or designated love interests. His preoccupation with environmentalism is conveyed both through his artistic style and overarching themes. As such, he forgoes traditional, fairytale villains and instead explores how modernization and industrialization pollute society both literally and figuratively. Ponyo, Spirited Away, and Howl’s Moving Castle are three such retellings of Western fairytale tropes, inscribed with Miyazaki’s whimsical touch.

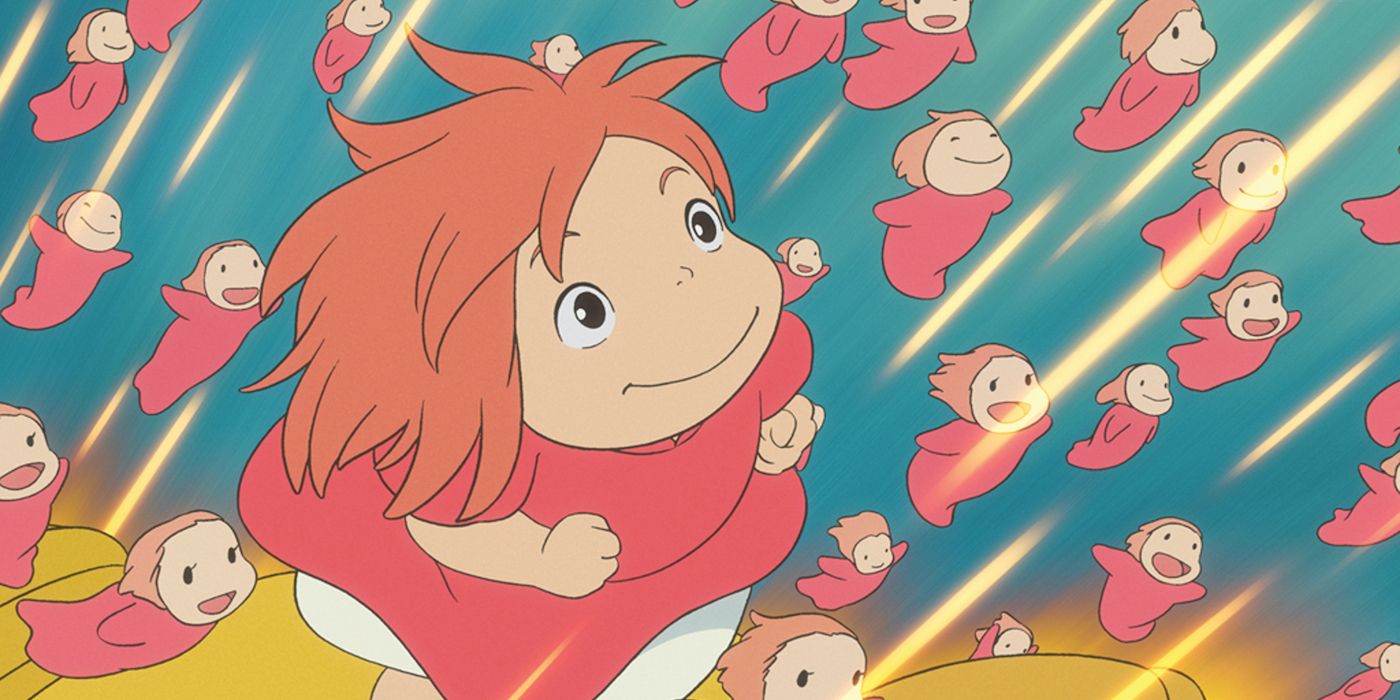

'Ponyo' Gives a New Take on "The Little Mermaid"

Ponyo is the straightest example of a Western fairy tale reinvented by Miyazaki, as it is directly based on Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid. Brunhilde (Noah Cyrus), takes the role of Ariel in the film, right down to her vivid red hair, as a ‘goldfish’ who seeks independence on land, apart from her domineering, wizard/scientist father, Fujimoto (Liam Neeson). Rather than taking the usual romantic route, Brunhilde’s desire for independence is sparked by her friendship with the human boy Sōsuke (Frankie Jonas), who names her Ponyo. Friendship and familial bonds are a central aspect of Miyazaki’s stories, and in Ponyo, he explores how these relationships can become a point of contention as a reflection of the difficulties of growing up and apart from one’s family. As Ponyo and her father disagree over her ambitions, magical elements become intertwined with the conflict, and it is here that Miyazaki’s environmentalism becomes apparent.

Miyazaki often creates his environments to appear as characters in their own right, victimized by human greed and selfishness. As a disastrous tsunami looms, the film emphasizes the awe-inspiring power of nature and the need to respect and balance it against one’s wishes. Several Japanese myths and legends have also influenced Ponyo such as the 19th-century poem Baika Hyoretsu, where a goldfish likewise undergoes a dramatic change via the contamination of human blood. Ponyo’s mother, Gran Mamare (Cate Blanchett) is a fascinating blend of the ‘Kannon’, the Japanese Goddess of Mercy, and ‘Thalassa’, the Greek primordial Goddess of the Sea, indicative of Miyazaki’s trademark fusion of cultures. Ponyo, through its gorgeous and grandiose depiction of the ocean itself and all the creatures that inhabit it, reminds its audience to reconnect and appreciate nature as a dazzling and magical entity in its own right.

'Howl’s Moving Castle' Is Miyazaki's Version of "Beauty and the Beast"

A retelling of the classic Beauty and the Beast trope, Howl’s Moving Castle is an adaptation of British author Dianne Wynne Jones’ novel of the same name. While the film faithfully adapts several aspects of the novel including the main setting and characterizations of the lead characters, Miyazaki instills his own preoccupations into the film to further reinvent the fairytale. The film focuses on Sophie Hatter (Emily Mortimer/Jean Simmons), a miller turned into an older woman whose only hope of breaking the curse lies in severing the connection between the wizard Howl (Christian Bale) and the demon Calcifer (Billy Crystal). As Sophie becomes Howl’s cleaning lady, she travels alongside him in his wondrous, flying castle and the two’s relationship thereby develops. As a reimagining of the fairytale, who is the Beauty and who is the Beast shifts throughout the narrative. The handsome but selfish Howl contrasts the (supposedly) plain but compassionate Sophie, and it is through mutual kindness and self-sacrifice that the two are freed of their cursed, ‘grotesque’ forms.

Unlike other fairy tales, Howl’s Moving Castle provides a biting critique of modernism in the film, with technological hubris considered the root of society’s ills. Sophie’s monotone, hometown is heavily contrasted with the wild and beautiful natural countryside, as a disconnection from nature renders much of the population pessimistic and dispirit. However, the director integrates his own Taoist beliefs by depicting industrialization as permissible and even awe-inspiring if it is aligned with nature. While Howl’s castle is mechanical-looking, it is also distinctly alive and magical, allowing two opposing elements to coincide peacefully when nature is respected rather than denigrated. In carefully combining differing cultures, tropes, and themes, Miyazaki created a romantic adventure where altruism, compassion, and the natural world intersect and remind us where humanity’s true values should lie.

'Spirited Away' Goes Down the Rabbit Hole Like "Alice in Wonderland"

Studio Ghibli’s most famous film bears a striking resemblance to Alice in Wonderland, with Spirited Away, likewise featuring a young girl who is drawn into a mysterious and corrupt world. While Alice finds herself falling through a rabbit hole, Chihiro Ogino (Daveigh Chase) explores an abandoned amusement park and finds a traditional bathhouse. There she fails to heed the warning of a boy named Haku (Jason Marsden) and returns to find her parents turned into pigs while the world around her has become a strange, supernatural entity. As with Alice in Wonderland, metamorphic animals and creatures are present in Spirited Away, fascinating and confusing Chihiro. However, Spirited Away embraces the uncertainty of the supernatural world and considers curiosity to be a valued and needed characteristic as one transitions into adulthood. Likewise, while Yubaba (Suzanne Pleshette) may seem like the film’s main antagonist and another queenly figure, it is human greed and Western consumerism that Miyazaki criticizes and considers to be the polluting factor of society.

Unlike the other two films discussed, Spirited Away is the most Japanese in character as it incorporates the nation’s folklore through its depiction of spirits, known as Kami. Kami are venerated in Shinto folklore and are deeply intertwined with nature, inhabiting a mirrored but complementary world to our own. Among the many Kami are the shadowed and masked creatures who float throughout the supernatural world as well as the workers and inhabitants of the bathhouse, including the peculiar Radish Spirit (Jack Angel). Yōkai, a specific class of supernatural entities are also present and includes the humanoid spider Kamaji (David Ogden Stires), based on the Tsuchigumo. Spirited Away’s most famous creature ‘No-Face’ (Bob Bergan) is likely influenced by the faceless Noppera-bō Yökai, while its gluttonous form resembles the ‘Hungry Ghosts’ in wider Asian folklore, known as Gaki in Japan. Miyazaki utilizes the spirits to convey the corruption of greed, consumerism, and disconnection from nature and traditional beliefs, representative of the influence that Western values and capitalism have had on Japan.

Hayao Miyazaki’s films transcend the traditional tropes of fairy tales, allowing modern and natural elements to conflict and coincide. He shifts the existing narratives to elevate his female protagonists while exploring his own themes and concerns. His films are a reflection of society’s true corruptions, rather than villainizing specific individuals and offering easy solutions to more complicated problems. By creating such fantastical worlds, Miyazaki has re-contextualized classic fairy tales for contemporary audiences that can be rewatched over and over again, whether as a curious child or a nostalgic adult.